To Dee, Richard, Jenny and Rachael

BLOOMSBURY WILDLIFE

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland

This electronic edition published in 2021 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY WILDLIFE and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in the United Kingdom 2021

Copyright Martin Warren, 2021

Martin Warren asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work

For legal purposes the constitute an extension of this copyright page

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-4729-7525-6 (HB)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-7523-2 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-7522-5 (ePDF)

Jacket artwork by Carry Akroyd

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters.

HALF TITLE: Small Blue.

FRONTISPIECE: Swallowtail.

Contents

Chalk Hill Blues basking in the evening light before roosting.

A common misconception about butterflies is that they are dainty, fragile creatures, blown about by the wind and at the mercy of the elements. Down the ages, they have often been seen as vaguely otherworldly, as if they come from a spirit world beyond the earth. The Greeks named them psuche, our psyche, which is the same word as the Greek for mind or soul. In our own age, 2,000 years on, their delicate beauty seems to symbolise the vulnerability of the natural world in the face of the juggernaut of humanity.

In this book, I will show that butterflies are not, in fact, particularly fragile, or at least no more than any other insect. They are, rather, tough survivors in a highly competitive world in which a myriad of other species regard them as food. Butterflies are the culmination of millions of years of evolution, with each species finely honed to its environment. Every stage of their life-cycle, from egg, to voracious caterpillar, to dormant chrysalis, to winged adult, has, in effect, been perfected.

I became fascinated by butterflies and moths as a young child. But at first it was not the adults that excited me as much as the caterpillars. I found hairy woolly bears, looping inch-worms, spiny ones, bobbly ones, even caterpillars with little tussocks and brushes studded along their backs. All of them captured my imagination and drew me into their miniature world. I collected them in pots and cages, found the right plants for them to feed on, and watched each caterpillar grow and finally turn into a chrysalis. I remember, too, watching breathlessly, as my first butterfly struggled from the dry skin of its chrysalis to unfurl its wings and fly. I felt curiously honoured, the boy explorer of a new world.

Most of my caterpillars turned out to be moths. But I didnt care. I collected and reared as many kinds as I could. Watching the adults emerge was as exciting as opening a present at Christmas. To me they made the perfect pets. No cat or dog would transform itself before my very eyes and turn magically into such a beautiful creature. No other captive animal offered the wonderful variety of butterflies and moths. I felt as proud as a parent as each one emerged and took its freedom.

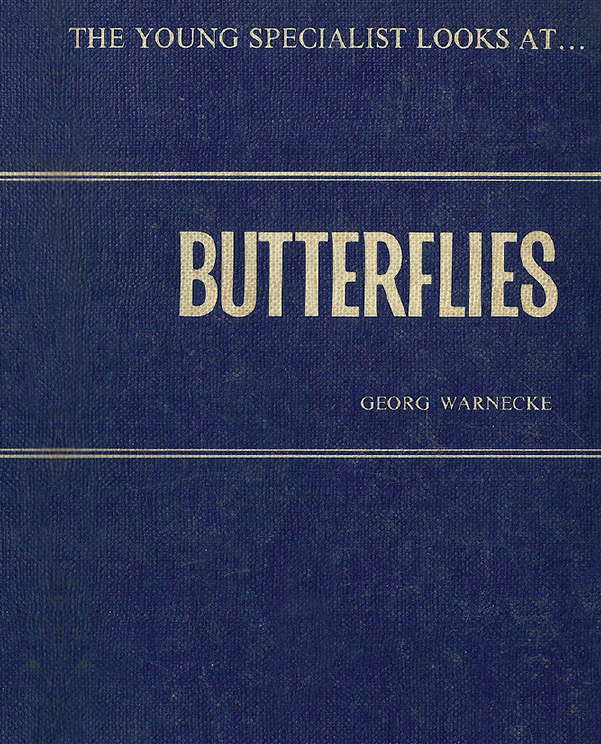

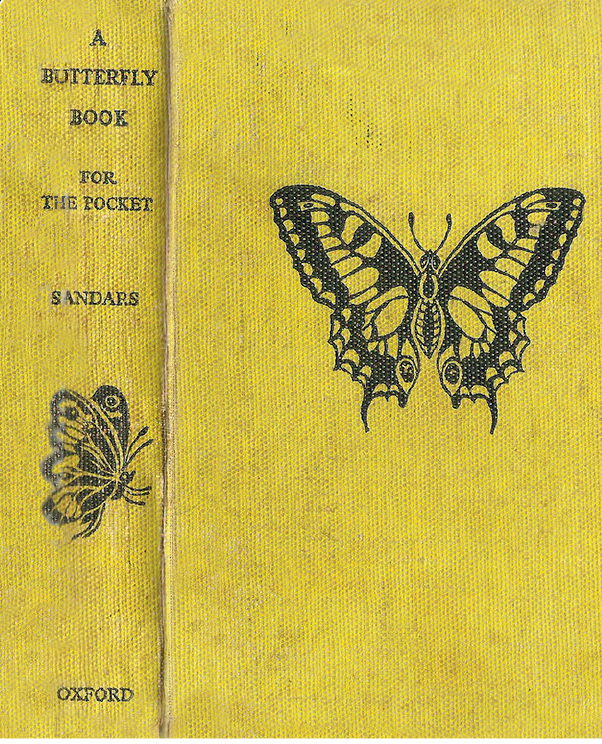

My early inspiration came from books like The Young Specialist Looks At Butterflies by Georg Warnecke (1964) and A Butterfly Book for the Pocket by Edmund Sandars (1939).

To begin with, my bibles were The Young Specialist book on butterflies and Edmund Sandars A Butterfly Book for the Pocket, although I soon graduated to The Observers Book of Butterflies and The Observers Book of Larger Moths, and then on to more grown-up books. They told me a little about rearing caterpillars and a bit about their intricate life-cycles. But the details were sketchy at best, and I had to learn the hard way, by trial and error. Of course there were casualties, but each failure spurred me on to do better next time, and learn more about my craft. For example, I remember my disappointment when a plump little moth emerged from its cocoon with what I thought were deformed wings. But, as it turned out, the moth was perfectly healthy. It was a female Vapourer moth, which is naturally wingless (in fact it has vestigial wings that are incapable of flight). A harsher lesson happened when a caterpillar erupted into clusters of white parasitic cocoons. But my initial horror turned to fascination as I read about the life of these tiny flies which lay their eggs inside an egg or caterpillar and feed inside the living body until ready to burst out, alien-like, from the dying host.

It was not long before I began to gravitate towards butterflies. They were easier to see than moths, especially when they gathered to feed on the large Buddleja bush in the garden: including colourful Peacocks, Small Tortoiseshells, Red Admirals. I found other butterflies as we walked the chalk hills near my home in Dunstable, Bedfordshire. I was lucky to have a mentor in an elderly neighbour who owned an impressive hoard of bird eggs (gathered in the days when bird-nesting was still legal) as well as a collection of pinned butterflies and moths. Under his guidance I made a small collection of my own, trying to get a male and female of each species. With my two chums, Bob and Barney, I scoured the downs and lanes in search of new species. As Peter Marren remarks in his eulogy to butterflies, Rainbow Dust (2015), we were the last generation to collect butterflies with a clear conscience. Today the net and the killing bottle have long since been replaced by the camera.

My collecting phase was short-lived. For me, dead butterflies were no match for living ones and I began to travel further afield in search of more exotic species. In time, this childhood crush turned into a fascination for butterflies that has lasted my whole life. By great good fortune I was able to turn it into a career. When I graduated in zoology at Imperial College London, I had first thought of a medical career. But instead, partly inspired by Rachel Carsons