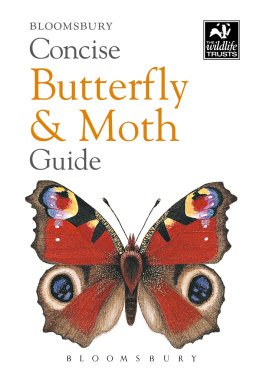

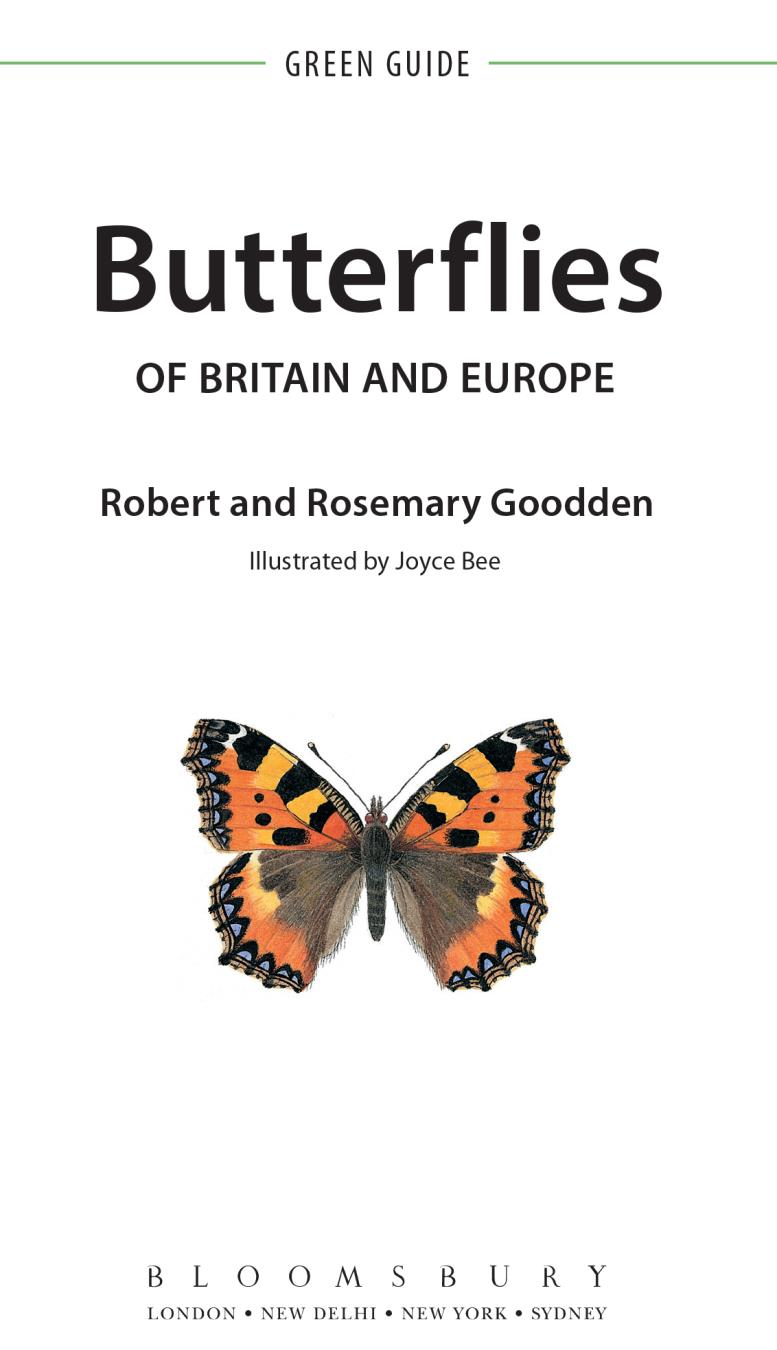

Bloomsbury Natural History

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square | 1385 Broadway |

London | New York |

WC1B 3DP | NY 10018 |

UK | USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

This electronic edition published in 2016 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2001 by New Holland UK Ltd

This edition first published 2016 by Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2016

photographs Shutterstock, 2016

Robert and Rosemary Goodden have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN: PB: 978-1-4729-1642-6

ePDF: 978-1-4729-3338-6

ePub: 978-1-4729-1643-3

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

Introduction

When setting out in search of butterflies for the first time, you should not expect to encounter a myriad of species or large numbers colonising a small area. Butterflies should be looked for in particular types of locality and in regions noted for their Lepidoptera (the scientific order of butterflies and moths).

For instance, a visitor from Britain to the north coast of France will note that the fauna and flora are only a little different from those at home. There are more species to be found but the range becomes greater, and butterflies more numerous, the further south you travel. South of the Loire the potential increases.

There is, however, a sense of anticipation of what is in store. The butterfly enthusiast might be forgiven for hoping to find some excitement round every corner and, indeed, the possibilities of finding the unusual are much greater. A windblown object resembling a leaf just might be an interesting creature, never before encountered. Branches heavily denuded could reveal a colony of some colourful caterpillar that is either rare or does not exist at home. The travelling naturalist will know the feeling well.

Mountainous regions are often well populated, especially in parts of the Alps. Scandinavia has interesting polar species in the extreme north. Centrally there is a gap which is too far north for many of the central European species and too far south for Arctic ones. Clearly, industrialised areas are less productive for butterflies, so it is understandable that sparsely developed parts of central Europe (The Czech Republic, Poland and south to the Balkans) have wonderful butterfly habitats. Further south, Spain has a very rich butterfly fauna and this is equally true of areas spreading east through southern France, Italy to Greece.

The butterflies on the British List number about 68. In the whole of Europe, there are more than 360 species. Those living in tiny pockets, or at the extremities of the Continent, are not included in this book but, with the exception of some Skippers (Hesperiidae), it has been possible to include most of the butterflies which are likely to be encountered in Europe.

Distribution mentioned in the text for each species refers to mainland regions rather than islands, which tend to have a smaller range of species than nearby mainland. Information on specific island butterfly fauna may be partially available in more comprehensive books but often has to be researched by ones own efforts work that can be very interesting.

The size given for each species indicates the approximate wingspan.

The symbols and abbreviations which appear on the illustrations denote the following:

| male |

| female |

gen 1 | 1st generation or brood |

gen 2 | 2nd generation or brood |

N | northern form |

S | southern form |

var | variation |

The Life Cycle of a Butterfly

Butterflies have a complete metamorphosis, involving four distinct stages in the life cycle. These stages are: egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa (chrysalis) and adult.

THE EGG

Eggs may be laid singly, in small groups or in batches, depending on the habits of the individual species. All are visible to the naked eye but they are very small. With a lens, a great deal of interesting detail can be observed and under a low-powered binocular microscope a whole new world of beauty and fascination is opened up. Each species lays eggs that are individual in shape, pattern and colouring. The general characteristics of a family may be observed from the egg, just as this is possible with the adult butterfly itself. The Pierids lay eggs that are tall and bottle-shaped, usually yellow or orange. The Coppers lay eggs that are round, with a very complex and angular construction, deeply pitted and nearly as regular as the pattern of a snowflake.

The duration of the egg stage is dependent on temperature and varies with the species. A typical time would be from two to three weeks and there are hibernating species which remain as eggs from late summer until the following spring.

The outer shell of the egg is rigid, sometimes hard. There is a central closed orifice, the micropyle, through which the egg was fertilised inside the female abdomen, and through which the developing larva is able to breathe. The larval embryo gradually develops by cell division, from almost nothing but a liquid to a fully formed and efficient eating machine. The mandibles are strong and designed to pierce the eggshell once the larva is ready to hatch. A hole is eaten, just large enough to allow the head to break through, and the larva pulls its way out with quite a rapid movement.

THE LARVA

Larvae grow continuously and may become a thousand times their original size and weight. Their main purpose is to eat and grow. Their skin is elastic but cannot expand enough to accommodate the dramatic increase in size from the newly hatched larva to the final stage, prior to pupation. The problem is solved by changing the skin at intervals, each new one being much larger than the previous one. There are usually at least four skin changes and the periods between changes are known as instars. The first instar lasts until the first skin change and the final stage is the fifth instar, which is followed by pupation. The scientific term for a skin change is ecdysis.

Next page