Praise for Jim Crumleys previous nature books

Shortlisted for a Saltire Society Literary Award, 2014 for The Eagles Way

Crumley conveys the wonder of the natural world at its wildestwith honesty and passion and, yes, poetry.

Susan Mansfield, Scottish Review of Books

Scotlands pre-eminent nature writer. Jim Perrin

Jim Crumley soars with eagles and we watch with our mouths open, not just because the presence of the eagle fills us with awe but the virtuoso writing does, too.

Paul Evans , BBC Countryfile Magazine

Crumleys distinctive voice carries you with him on his dawn forays and sunset vigils. John Lister-Kaye, Herald

The best nature writer working in Britain today.

David Craig , Los Angeles Times

Enthralling and often strident. Observer

Compulsively descriptive and infectious in its enthusiasm. Scotland on Sunday

Glowing and compelling. Countryman

Every well-chosen word is destined to find its way into our hearts and into our minds and into our imaginations.

Ian Smith, The Scots Magazine

Well-written elegant. Crumley speaks revealingly of theatre-in-the-wild. Times Literary Supplement

Also by Jim Crumley

Nature writing

The Eagles Way

Encounters in the Wild: Barn Owl

Encounters in the Wild: Fox

The Great Wood

The Last Wolf

The Winter Whale

Brother Nature

Something Out There

A High and Lonely Place

The Company of Swans

Gulfs of Blue Air (A Highland Journey)

The Heart of the Cairngorms

The Heart of Mull

The Heart of Skye

Among Mountains

Among Islands

Badgers on the Highland Edge

Waters of the Wild Swan

The Pentland Hills

Shetland Land of the Ocean

Glencoe Monarch of Glens

West Highland Landscape

St Kilda

Fiction

The Mountain of Light

The Goalie

Memoir

The Road and the Miles

Urban landscape

Portraits of Edinburgh

The Royal Mile

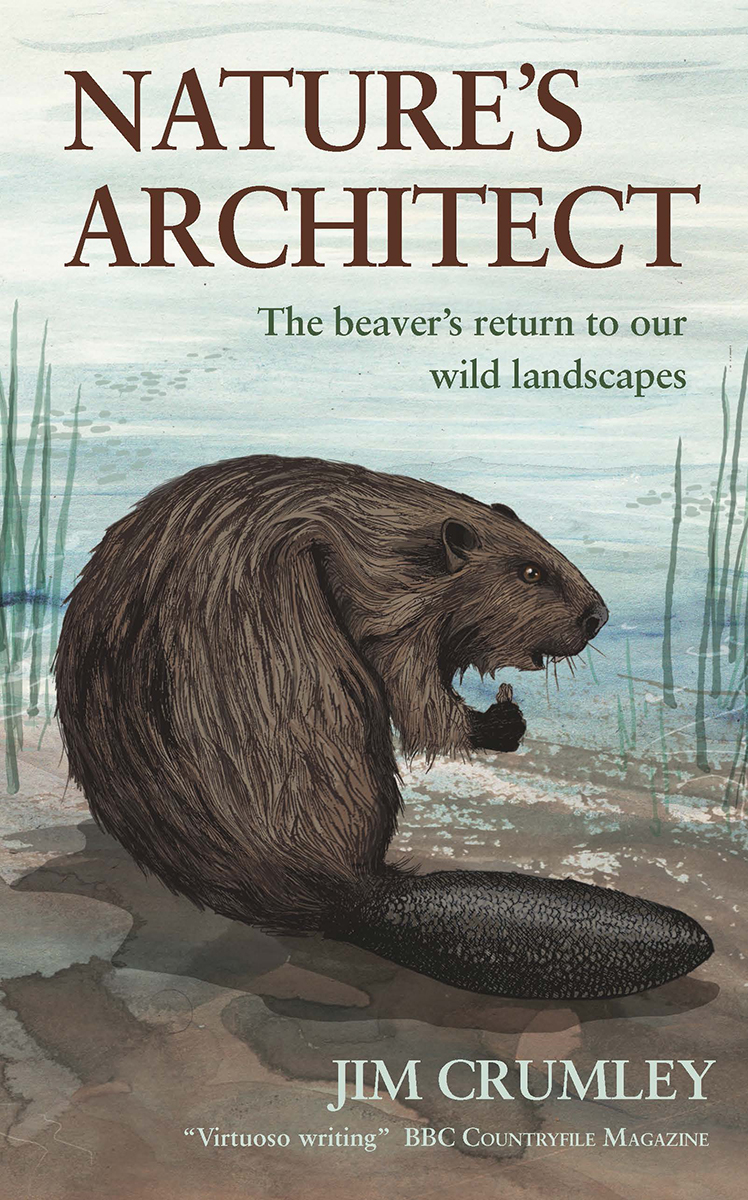

Natures Architect

The beavers return to

our wild landscapes

JIM CRUMLEY

Contents

To the beaver pioneers

John Lister-Kaye

and Paul Ramsay

and to Don MacCaskill

for daring to dream

If no exaggerations had ever appeared in connection with the beaver, except those referring to its performances in felling trees, the stock of these alone would have been sufficient to damage the reputation of Natural History writers.

Horace T. Martin, Castorologia

(W. Drysdale, Montreal, 1892)

Chapter 1

Liquid Architecture

The mother art is architecture.

Frank Lloyd Wright

Study nature, love nature, stay close to nature. It will never fail you.

Frank Lloyd Wright

The beaver was the original inventor of reinforced concrete. He has used it for a million years, in the form of mud mixed with sticks and stones

Ernest Thompson Seton

Liquid architecture. Its like jazz you improvise, you work together, you play off each other, you make something

Frank Gehry

IT OCCURS TO ME from time to time that there are three things I might have become: a nature writer, a jazz guitarist, or an architect. Of these three, nature writing has been my day job (and often my night job too) for nearer thirty years than twenty now; my jazz guitar playing is something of a well-kept secret, a handful of gigs a year where the first criterion to satisfy is that the audience outnumbers the band; and I have more chance of walking on water or flying unaided somewhere over the rainbow than becoming an architect because (a) I cant draw, and (b) having to think in three dimensions is usually at least one too many for me and sometimes two. Then I discovered beavers, for which architecture, inspired improvisation, and reworking nature into dazzling essays, are simply the stuff of life itself. In other words, all three of my preferred lifestyle alternatives co-exist within any one member of the beaver tribe in more or less equal parts. Working with nature can be a humbling experience for a mere mortal.

I love that phrase of Frank Gehrys liquid architecture. It might have been invented for a book about beavers. Beavers build landscapes from scratch and from water that flows and timber that grows in the wrong place. All life is improvised liquid architecture, to which end water must be taught not to flow and timber not to grow, at least not there, but rather where the one can be purposefully redirected and the other artfully felled, reposed and metamorphosed into dam, lodge, bridge, larder, fridge; and water must not flow there but rather use this new canal, these new plunge pools, those channels one-beaver-wide for fast returns to deep water from the woods whenever danger manifests itself.

Frank Gehry is a bit of a hero of mine. Some of his buildings haunt me. In a good way. I admire original voices in all artforms, people who have studied the tradition of their art but then they take it to places it has never been before. Frank Gehrys architecture does that to the extent that some of his buildings look impossible to me. Yet still their landscapes adopt them, claim them, embrace them, so that soon you cannot imagine those landscapes without those buildings.

I read a newspaper article about his Fondation Louis Vuitton art museum in Paris that opened in October 2014. The article quotes the architect about the buildings design:

You have to keep that sketch quality. Anything overtly finished is static to me. Its not living We made the building ephemeral like a big sculpture. Its floating and changing. It looks like its growing. No matter what you do with a normal building, its a static building. This one isnt.

The author of the article, Jay Merrick of The Independent , observed:

Each structural element of the Fondation Louis Vuitton, and every piece of glass, is a one-off Frank Gehry has produced a building that comes together as if its also just about to fall apart

And then I asked myself an interesting question: Do you suppose Frank Gehry ever watched beavers?

***

The top of the bank is thirty feet above the river. The bank is well wooded with oak, sycamore, willow, ash, birch, but especially oak. The densely mixed understorey is much corrupted by copious stands of Japanese knotweed, except that here and there it looks as if it has been trampled underfoot by a passing posse of buffalo, but this being Perthshire and the edge of the Highlands of Scotland, there has to be another explanation. There is.

There is a clue fifty yards away on the opposite bank. It is a long, low barrier of apparently randomly collected sticks, but with a flattish top and regularly sloping sides; imagine that someone had scraped the top off a bar of Toblerone. It seals off a narrow pool of still water from the mainstream. And the downstream end of the barrier is bedecked with a giant bouquet of knotweed leaves and a handful of late purplish-pink blooms. It is late October and the leaves are yellow and pale green and almost orange. They catch the sun and the breeze and my eye, and they make a fine show. But there is no knotweed growing on the far shore. That exuberant bouquet has been gathered from over here, carted down the bank (too steep and sodden and fankled by standing and leaning and fallen trees to be comfortably negotiated by me, but then I dont have four legs and a low centre of gravity), and ferried across the river through the boisterous, throaty, midstream current, which begins to gather momentum here for a series of rapids through a right-angle bend 200 yards away. It takes a seriously accomplished swimmer to cross that current, not to mention that such a swimmer must have had its hands and arms and possibly its mouth full of knotweed stems and abundant foliage at the time.