Contents

About the Book

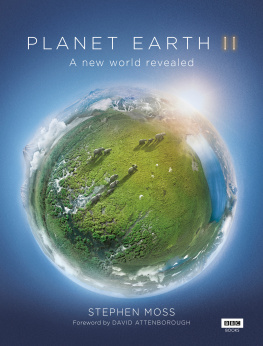

Can Britain make room for wildlife? Stephen Moss believes it can.

The newspaper headlines tell us that Britains wildlife is in trouble. Wild creatures that have lived here for thousands of years are disappearing, because of pollution and persecution, competition with alien species, changing farming and forestry practices, and climate change. Its not just rare creatures such as the Scottish wildcat or the red squirrel that are vanishing. Hares and hedgehogs, skylarks and water voles, even the humble house sparrow, are in freefall.

But there is also good news. In Newcastle, otters have returned to the river Tyne and red kites are flying over the Metro centre; in Devon, there are beavers on the River Otter; and peregrines the fastest living creature on the planet have taken up residence in the heart of London.

Elsewhere in the British countryside things are changing too. What were once nature-free zones are being rewilded; giving our wild creatures the space they need not just to survive, but also to thrive.

Stephen Moss has travelled the length and breadth of the UK, from the remote archipelago of St Kilda to our inner cities, to witness at first hand how our wild creatures are faring, and offers us this complex, heartfelt and often unexpected response.

About the Author

Stephen Moss is a naturalist, broadcaster, television producer and author. In a distinguished career at the BBC Natural History Unit his credits included Springwatch, Birds Britannica and The Nature of Britain. His books include A Bird in the Bush, A Sky Full of Starlings, The Bumper Book of Nature and Wild Hares and Hummingbirds. Originally from London, he now lives with his wife and children on the Somerset Levels.

ALSO BY STEPHEN MOSS

A Bird in the Bush

Birds and Weather

Birds Britannia

A Sky Full of Starlings

The Bumper Book of Nature

This Birding Life

Wild Hares and Hummingbirds

WITH BRETT WESTWOOD

Natural Histories

Tweet of the Day

For Derek Moore, 19432014

Conservationist, birder, mentor and friend

STEPHEN MOSS

WILD KINGDOM

Bringing Back Britains Wildlife

INTRODUCTION

How much is a view worth? How do you cost account a landscape? Can a computer be programmed to evaluate bird song and the brief choreography of a young beech plantation against a May sky, a kestrel hovering in winter air? Is there a method of reckoning up the percentage in a persons inner replenishment from wild country?

Kenneth Allsop, In the Country (1972)

A DEEP, BOOMING sound, like a distant foghorn, resonates deep in the reed bed. Behind me a mechanical buzzing stops and starts: an angler reeling out his line, or an insect, perhaps? In the skies above, a loud honking, as two enormous birds drift overhead. Down below, an elegant, long-necked, Persil-white creature stands stock-still, before plunging a dagger-like bill into the water to spear a fish, its death throes glistening in the bright June sunshine.

Bittern, Savis warbler, a pair of cranes and a great white egret: four species of bird that have, during the past decade, made their home in the Avalon Marshes in Somerset. Four species that, until recently, were either very rare or completely absent from Britain. Now they live out their lives in a wetland created from an old industrial site; former peat diggings within sight of Glastonbury Tor.

Ten years ago, I moved with my young family down to Somerset from London. When we exchanged the metropolitan rat race for a more tranquil and fulfilling life in the English countryside, I knew that I was also swapping swifts for swallows, parakeets for lapwings, and insolent urban foxes for shy rural ones. What I didnt realise was that, before a decade was out, I would witness a complete transformation of this landscape and its wildlife.

When we moved into our new home, on the hottest day of the hottest month on record, none of these new arrivals was here. All have since colonised this corner of the West Country, adopting this magical landscape as their own.

They are not alone: each spring and summer, the air resounds with the calling of cuckoos, the buzzing of dragonflies and the hidden presence of hawkmoths. In autumn and winter, crowds gather to witness the massive murmurations of starlings performing their aerobatic displays as dusk falls.

Now, the wildlife is spreading out into the surrounding parishes. As I write, a buzzard is perched on our garden goalpost, where my children practise their football skills. On a December bike ride around the fields behind our house I see barn owls and bullfinches, bouncing roe deer and lithe, fast-moving stoats, and the occasional peregrine, cruising over the fields in search of its prey. In June the verges of the lanes are awash with cow parsley and the pinkish-purple flowers of great willowherb; while whitethroats shoot up from the hedgerows to deliver their scratchy song, and skylarks hang even higher in the azure skies. If there is a better place to live in Britain an even more wildlife-rich landscape, with so many exciting new inhabitants then Id love to know about it. In the meantime, for me, this is pretty close to paradise.

AND YET... IN the wider world, beyond my immediate horizons, I know that nature is not faring so well. The newspaper headlines, the reports and surveys, and the anecdotal evidence of so many people I meet and talk to, tell a very different tale. In much of Britains countryside, our wildlife is in big trouble. Species that have lived here for thousands of years are disappearing, under threat from pollution and persecution, competition with alien invaders, changing farming and forestry practices, and climate change.

During my own lifetime barely fifty years since I first became aware of the wild creatures with which we share this small island I have seen changes that could never have been foreseen. Who would have thought that house sparrows and hedgehogs, both so common and widespread that we simply took them for granted, would have suffered such catastrophic population declines? Who would have believed that generations of children would now be growing up without ever hearing the call of the cuckoo, a sound that for our rural ancestors marked the coming of spring? And who would ever have imagined that hares and skylarks, water voles and bumblebees, turtle doves and partridges, would all be in danger of disappearing from our rural landscape? It is clear that if we dont do something to stem these declines and soon we may lose some of our most charismatic creatures for ever.

What has happened to Britains countryside and its wildlife? How have we managed to create new landscapes, and attract such exciting new arrivals, at a time when so many of our wild creatures are under threat? Why and how did much of the British countryside turn into a wildlife-free zone? And now, at the eleventh hour, what can we do to turn the tide of decline and disappearance, bring these species back from the brink, and restore the special places where they live?