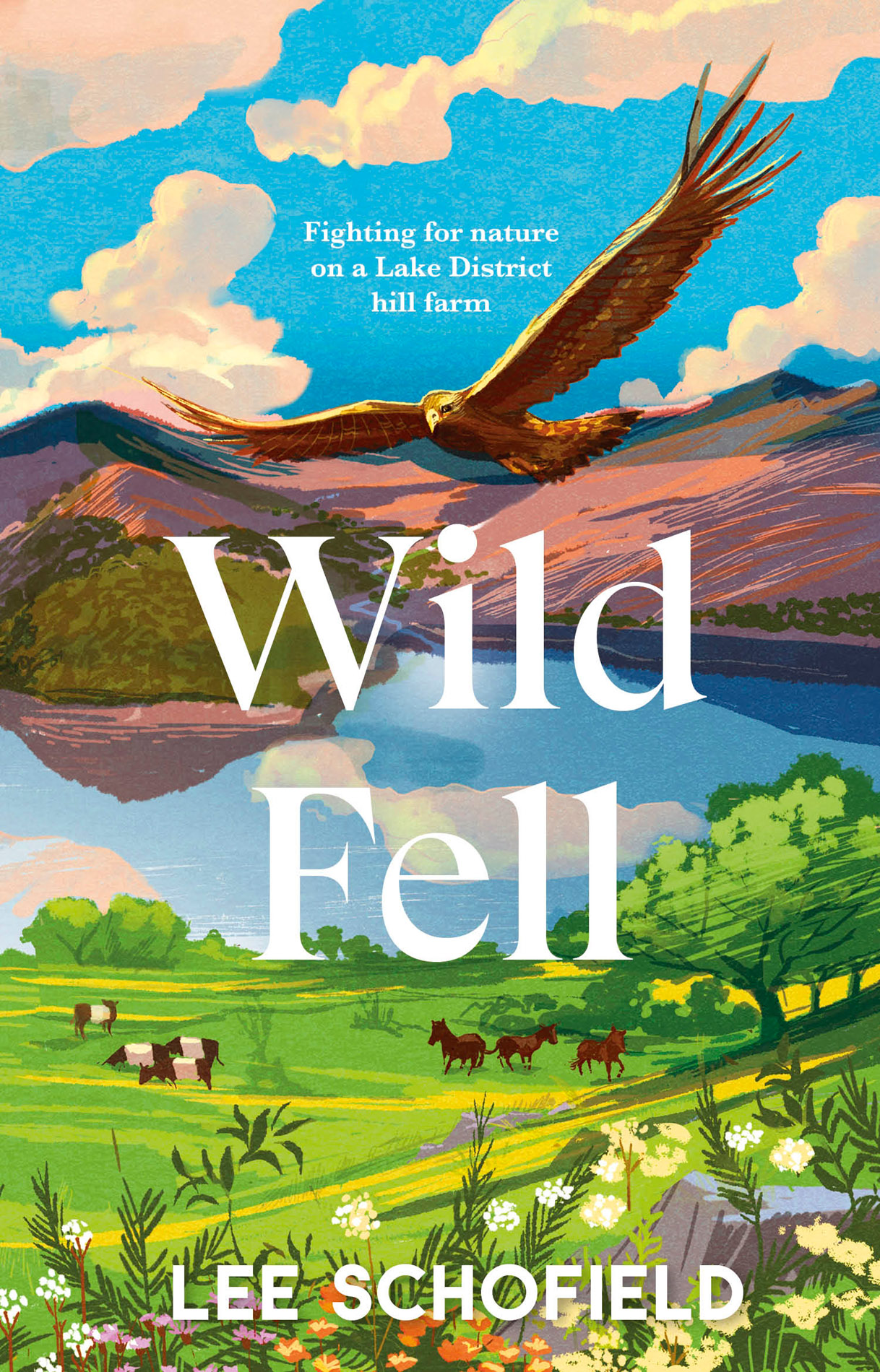

Lee Schofield

WILD FELL

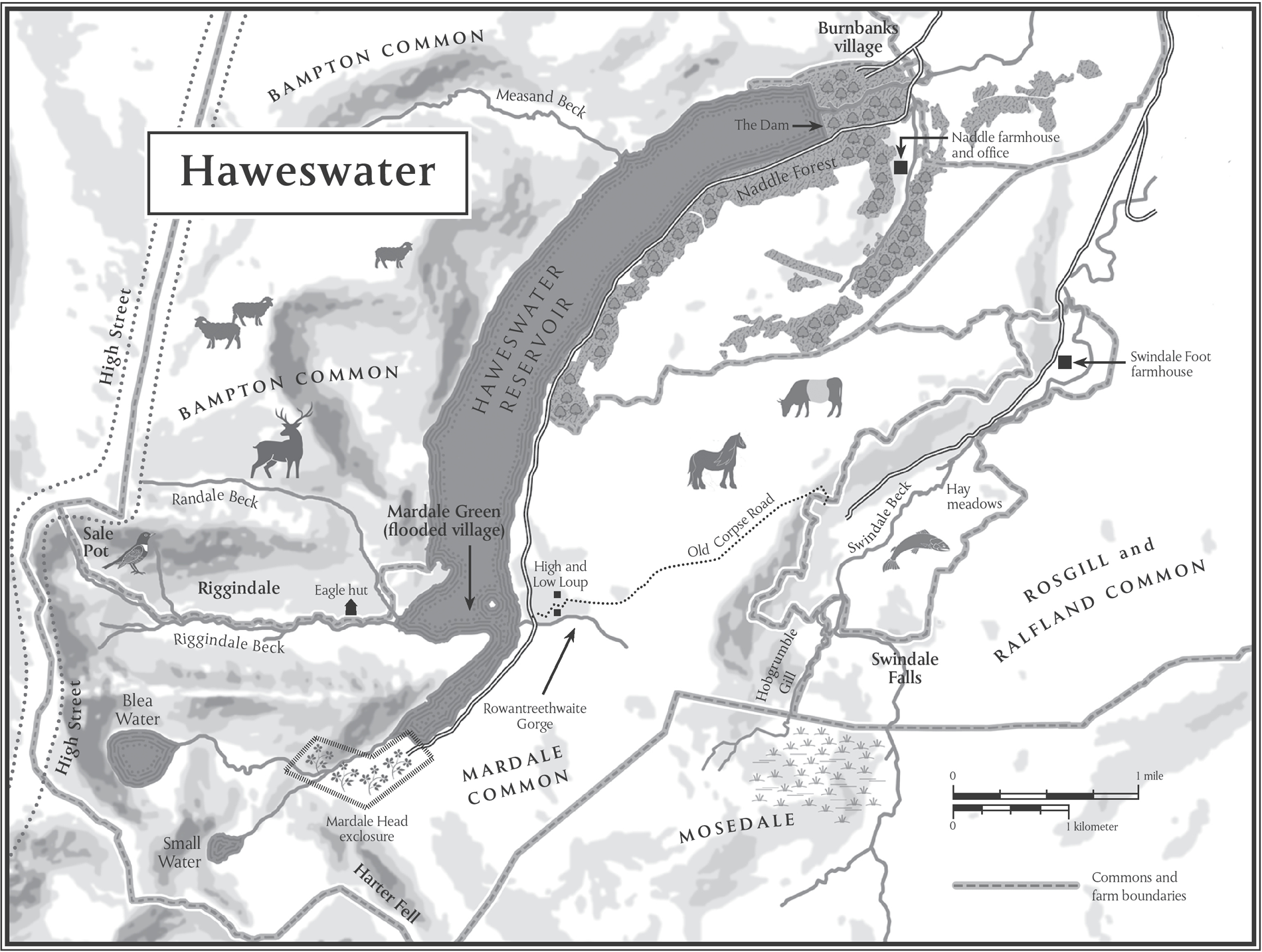

Fighting for Nature on a Lake District Hill Farm

Contents

About the Author

LEE SCHOFIELD is site manager at RSPB Haweswater in the Lake District, a landscape-scale nature reserve incorporating working farms. Wild Fell is his first book.

For Elliot and Aphra

Place Name Glossary

(near Swindale): The rocky height of the cattle-man (Old English/Old Norse)

Stream (from Old Norse; bekkr)

(Bampton Common): The hill where the bent-grass grows (Old English/Old Norse)

(Fidjadalen, SW Norway): The end of the blue mountain (Norwegian)

(Mardale Common): The dark lake (Old Norse/Modern English)

(Mardale Common): The steep path (Old Norse/Old English)

: Large stream or small river (Scotland)

(Scottish Borders): The fort of ravens (Celtic)

(above Ullswater): The steep path frequented by wild cats (Middle English/Old Norse)

(near Matterdale): The place where the black cock play (Old Norse)

COCKLE HILL (Bampton Common): The hill where the black cock play (Old Norse)

: The valley of the charcoal burners (Old Norse)

: Unenclosed pasture for communal use (Middle English)

: An amphitheatre-like valley formed by glacial erosion (from Gaelic; coire)

: Rocky height, major outcrop of wall or rock (from Gaelic; creag)

: Valley (from Old Norse; dalr)

: Hill, mountain, tract of high unenclosed land, high ground (from Old Norse; fell, meaning a single hill and fjall, meaning mountainous country)

: Mountain (Norwegian)

: Waterfall (from Old Norse; fors)

: Ravine with stream (from Old Norse; gil)

GLEDE HOWE (near Swindale): Kite Hill (Old Norse)

GOUTHER CRAG (Swindale): The rocky height with an echo (Old Norse)

: Great Paradise (Italian)

HARE SHAW (Mardale Common): Hare wood or copse (Old Norse). This hill is no longer wooded.

: The mountain frequented by deer (Old Norse)

: Hafrs Lake. Hafr being a personal name (Old Norse)

(Mardale Common, and many other Erne, Iron, Heron and Aaron crags elsewhere in the Lake District): The rocky height frequented by white-tailed eagles (from Old English; erne)

: The high paved road (anglicized from the original Latin name, Via Alta)

(Swindale): The rumbling ravine haunted by a hobgoblin or bogle (Old Norse)

(Bampton Common): The peak at the top of the steep path where the young goats go (Old Norse)

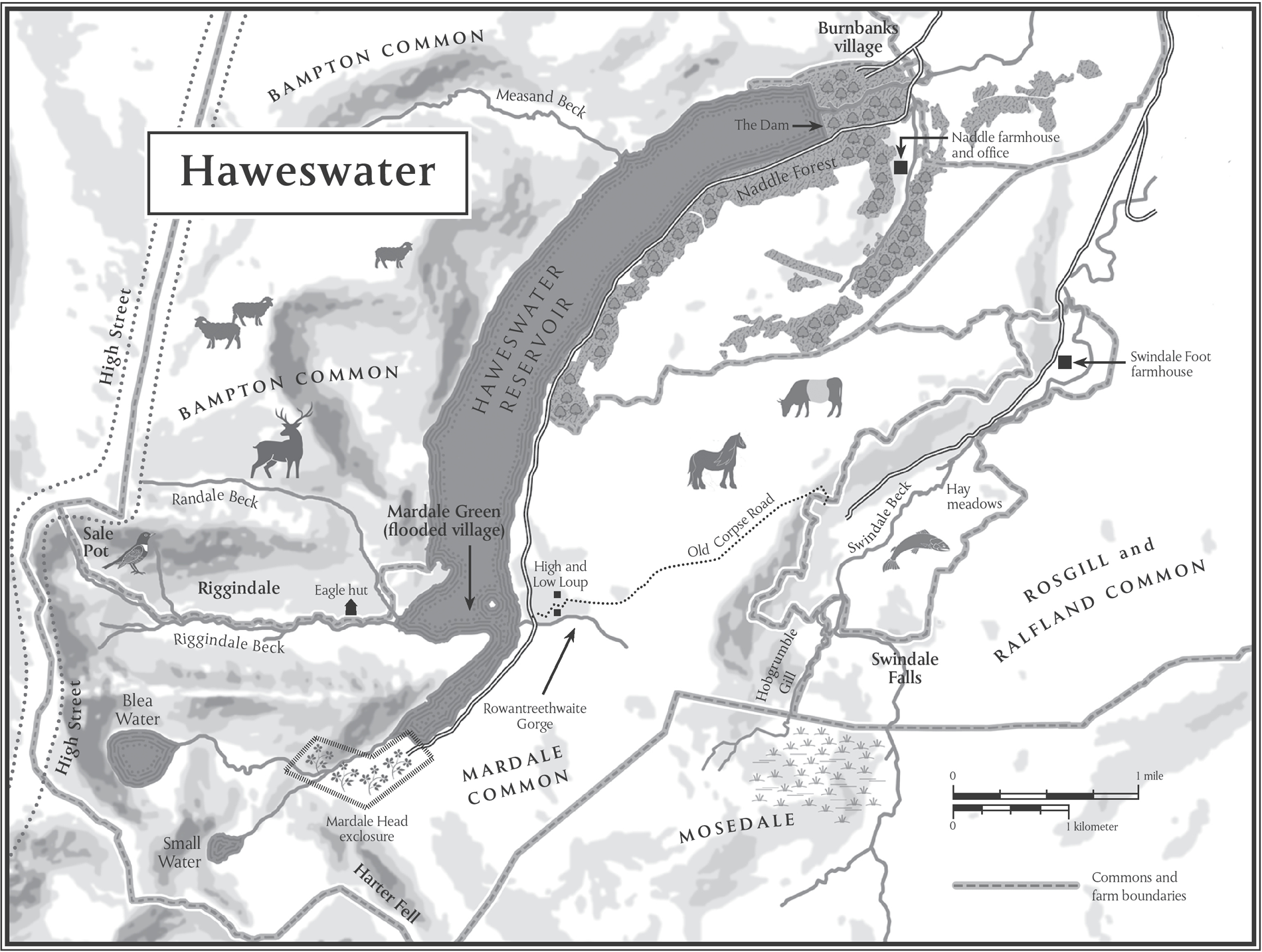

: The valley of the lake (Old Norse)

: The valley where the bedstraw grows (Old Norse)

(Matterdale): Bare hill (Cumbric)

(above Swindale): The valley with a bog (Old Norse)

: The wedge-shaped valley (Old Norse)

(Mardale and Bampton Common): The valley below the ridge (Old Norse)

(Ennerdale): The bright, light river (Old Norse)

(near Swindale): The ravine where the horses graze (Old Norse)

: The clearing with the rowan tree (Old Norse/Modern English)

: The valley where the pigs graze (Old Norse)

: Small mountain pool (from Old Norse; tjrn)

(near Swindale): The ridge above the wolf clearing (Old Norse). There are many places in the Lake District that include lfr, the Old Norse for wolf

(Mardale Common): The rocky heights frequented by wolves (Old English)

List of Illustrations

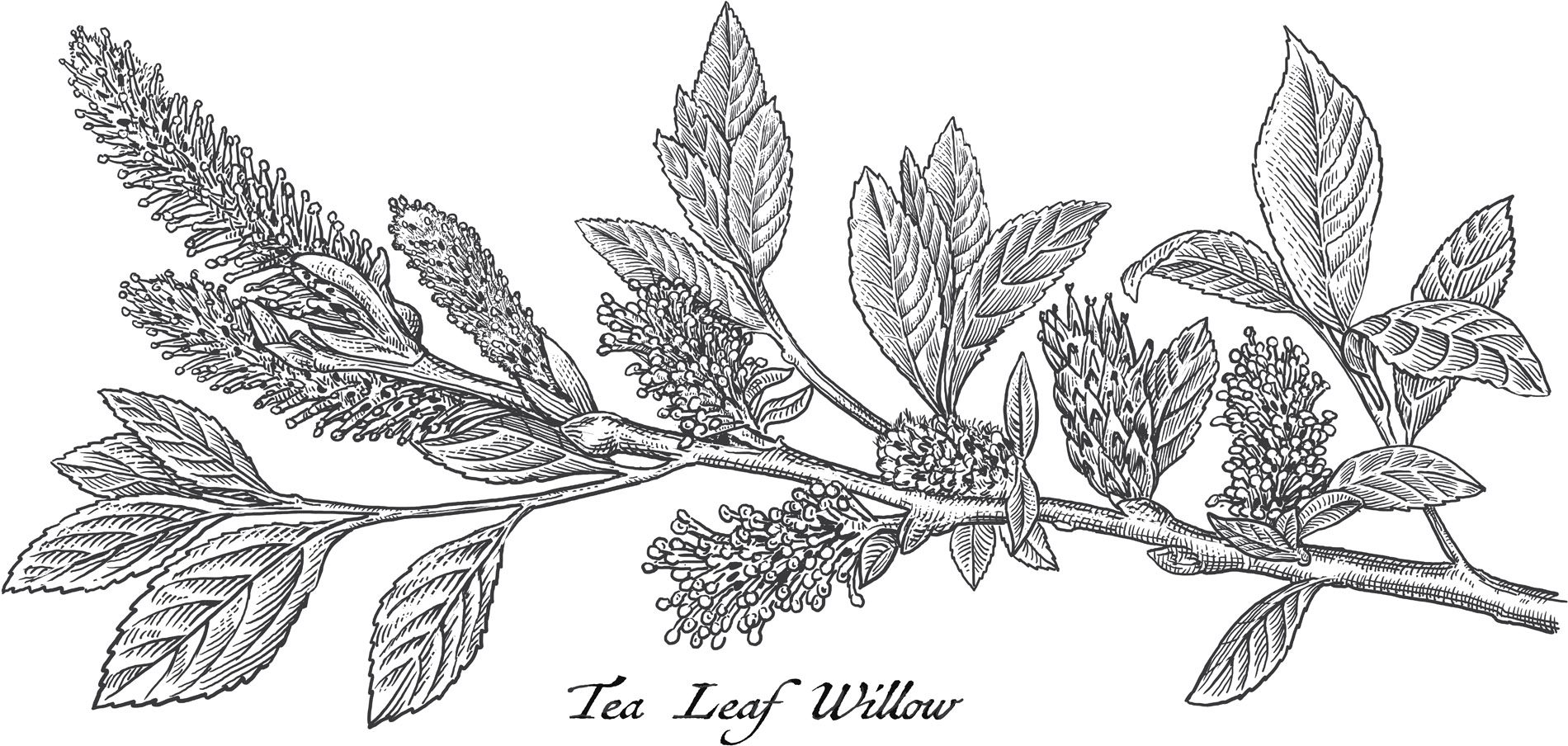

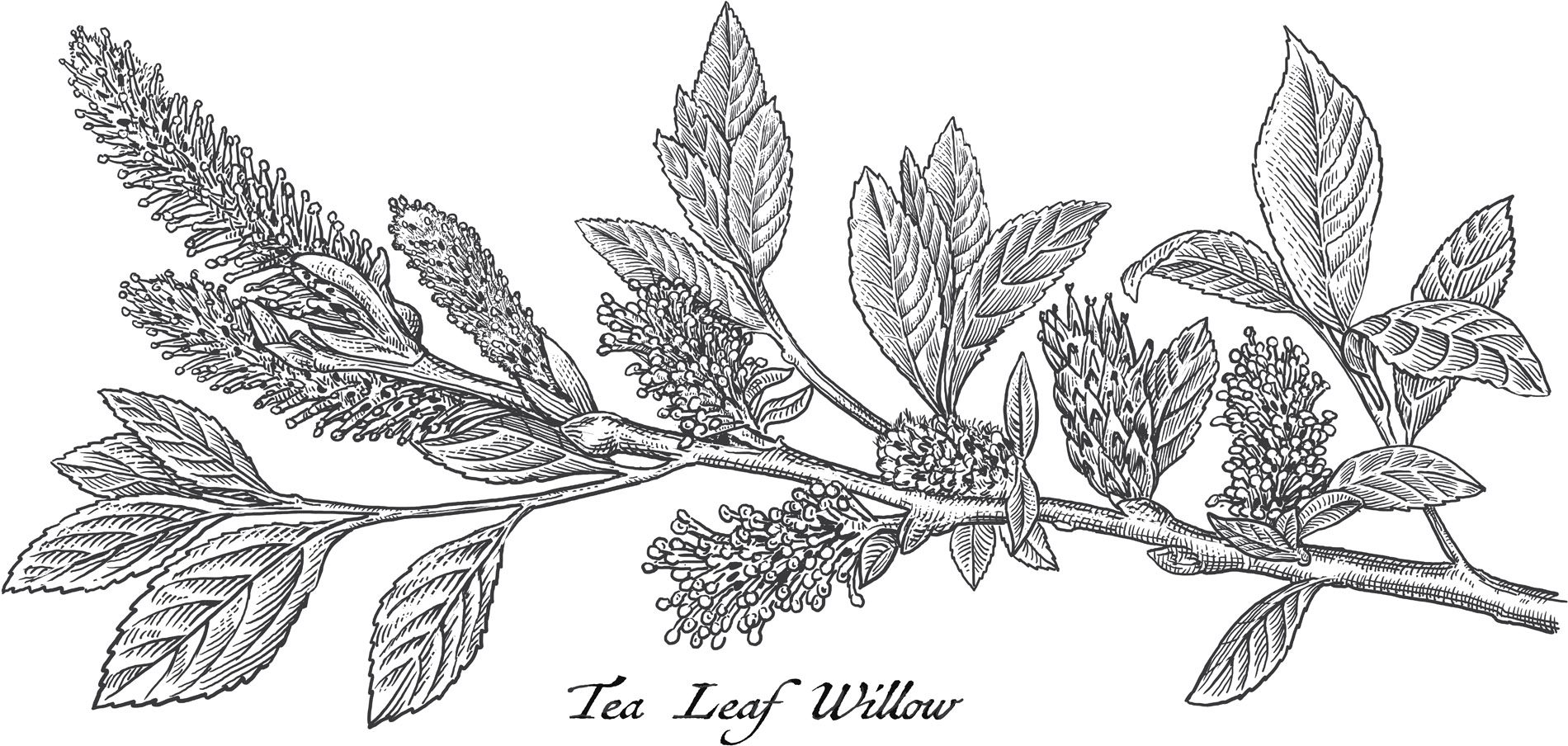

. TEA LEAF WILLOW

. GRASS OF PARNASSUS

. PYRAMIDAL BUGLE

. BUDDLEIA

. BILBERRY

. ROUND LEAVED SUNDEW

. MOUNTAIN EVERLASTING

. ALPINE SAW WORT

. ALPINE CATCHFLY

. TORMENTIL

. MOUNTAIN AVENS

. ASPEN

. BOG MYRTLE

. COMMON POLYPODY

. GLOBEFLOWER

. DEVILS BIT SCABIOUS

Introduction

The Willows

The mountain frequented by deer

(Old Norse)

Three straggly trees huddle on the fissured face of Harter Fell, high in the Lake Districts eastern corner. From thirty feet below, I can tell that they are willows, but I need to get closer to work out which species. With plenty of well-rooted birch and rowan to cling to, scrambling up the first part of the flower-hung is easy enough. The upper section, a few more degrees to the vertical, is a different matter. A loss of footing now would result in a slide, a plummet and a limb-breaking landing on the boulder scree below.

Few people set foot up here, leaving botanical treasures undiscovered in steep gullies and on brittle ledges. Water running over the crumbly, calcium-rich rocks forms patches of fertile rudimentary soil; great for flowers, not so great for climbing. Halfway up this slippery mess of a cliff, a solid-looking foot-long triangle of rock comes off in my hand, shattering on the ground below. I retreat with my pulse racing.

Working around the base of the crag, I find a gentler ascent via a narrowing grassy corridor, hemmed in by rising cliffs. As usual, my progress is slow, distracted every few steps by the summer wildflowers. Stone bramble, alpine ladys-mantle, northern bedstraw, lesser meadow-rue and starry saxifrage enliven the rocks, the poetry in their names adding to the allure of their shapes and colours.

The willows come back into view with just a narrow sloping slab bridging the gap between us, which I inch across, crab-fashion. I feel as if Im reaching hallowed ground. Growing beneath the unruly mesh of the willows branches are the fleshy stems of roseroot, the smooth oval leaves of devils-bit scabious, sturdy heather and vivid bilberry, a fragrant feast for any herbivore. That these plants are still here tells me that none have been brave or hungry enough to make the crossing. The soil is light and fluffy, with the rich mossy smell of an ancient oakwood. Any boot marks I leave will be quickly colonized, the plants erasing the evidence of my visit.

Their glossy green foliage tells me that these are tea-leaved willow, a species which grows in only a handful of places in the Lake District . No more than shoulder-height, their squat and sprawling form keeps them stable on their wind-battered refuge. The promise of such rare and beautiful plants makes botanizing in these crags intensely addictive. Theres always one more ledge to investigate, one more unexplored gully with secrets to uncover. Ive never made it back to the car anything less than hopelessly late.

Fast growing and producing huge quantities of tiny airborne seeds, willows are pioneers, quickly establishing in damp ground where the conditions are right. For thousands of years, willow bark has relieved human suffering its soothing power led to the development of aspirin. Perhaps herbivores can detect this medicinal benefit, adding to willows edible appeal. Smaller creatures are just as enticed; willows are second only to oaks in the number of insect species they support.

Next page