Foreword

Families have quarrels. Sometimes, they even have bust-ups and, as a consequence, split forever. Sociologists, had they been observing them at the time, might well have foreseen such ructions, long before the family itself realised what was happening. Animal sociologists ethologists to give them their proper name can often do exactly the same thing. Those studying animals that live in families, troops or herds, spend years observing such communities, trying to understand the rules that govern them, and they can, as a consequence, sometimes predict that animals are about to do the same sort of thing. What happens next can be not only dramatic but also very revealing of the nature of the animals themselves. But recording such events would be difficult.

Individual animals are often not as easy for us to identify as individuals of our own species. Sometimes ethologists have to attach radio-tags to the animals they are studying so that they are able to be absolutely certain of their identities. They also give them names so that they can easily describe what is happening or is about to happen. Usually the names they choose have no similarity to the names we use for our children and friends. They do that in order to avoid being accused of one of the cardinal sins of ethology anthropomorphism, that is to say, attributing human characteristics and emotions to an animal without adequate justification.

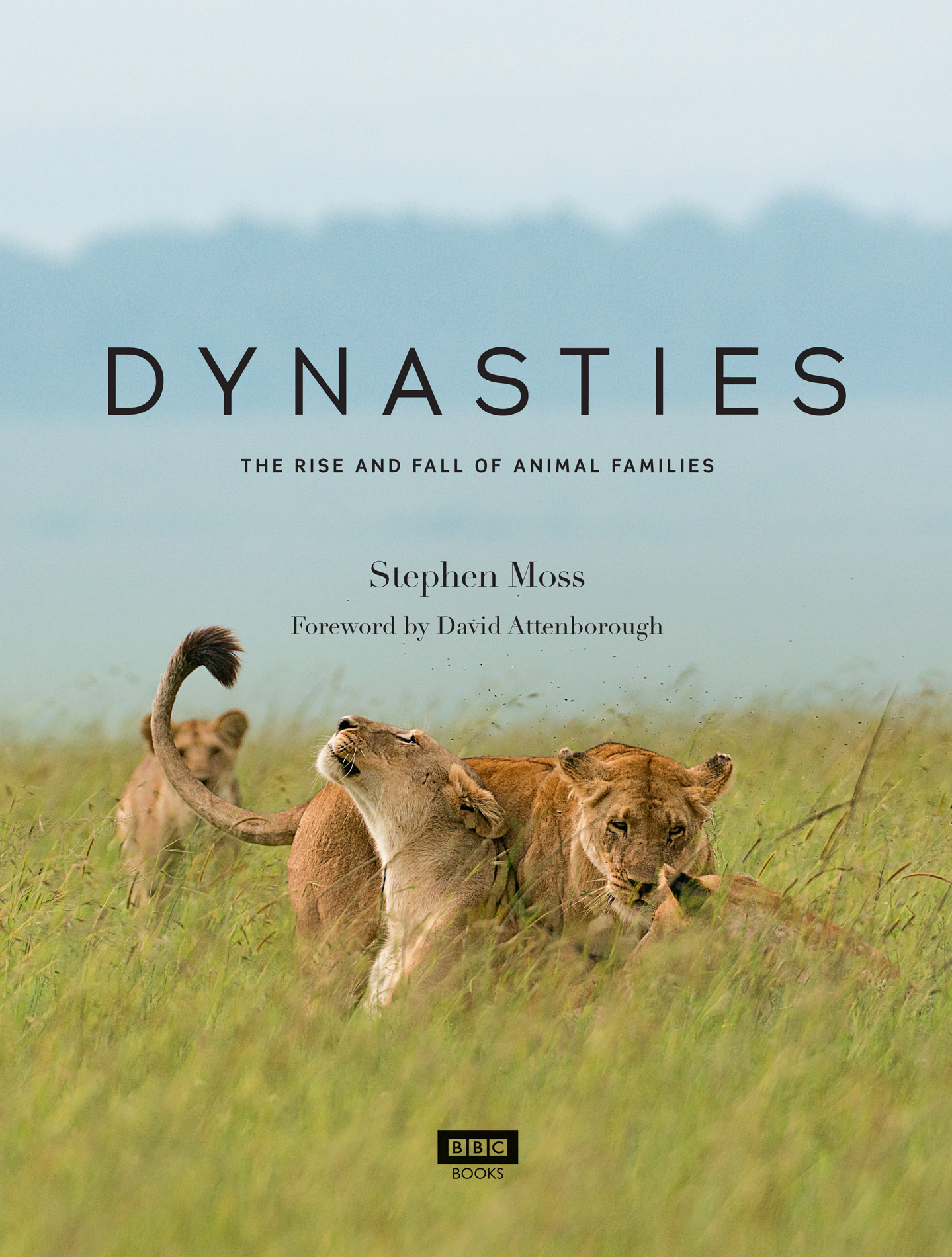

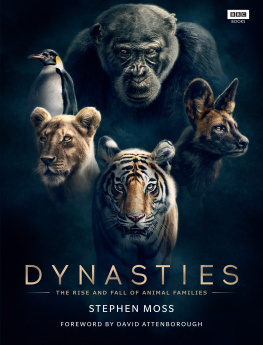

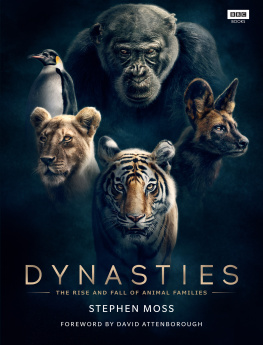

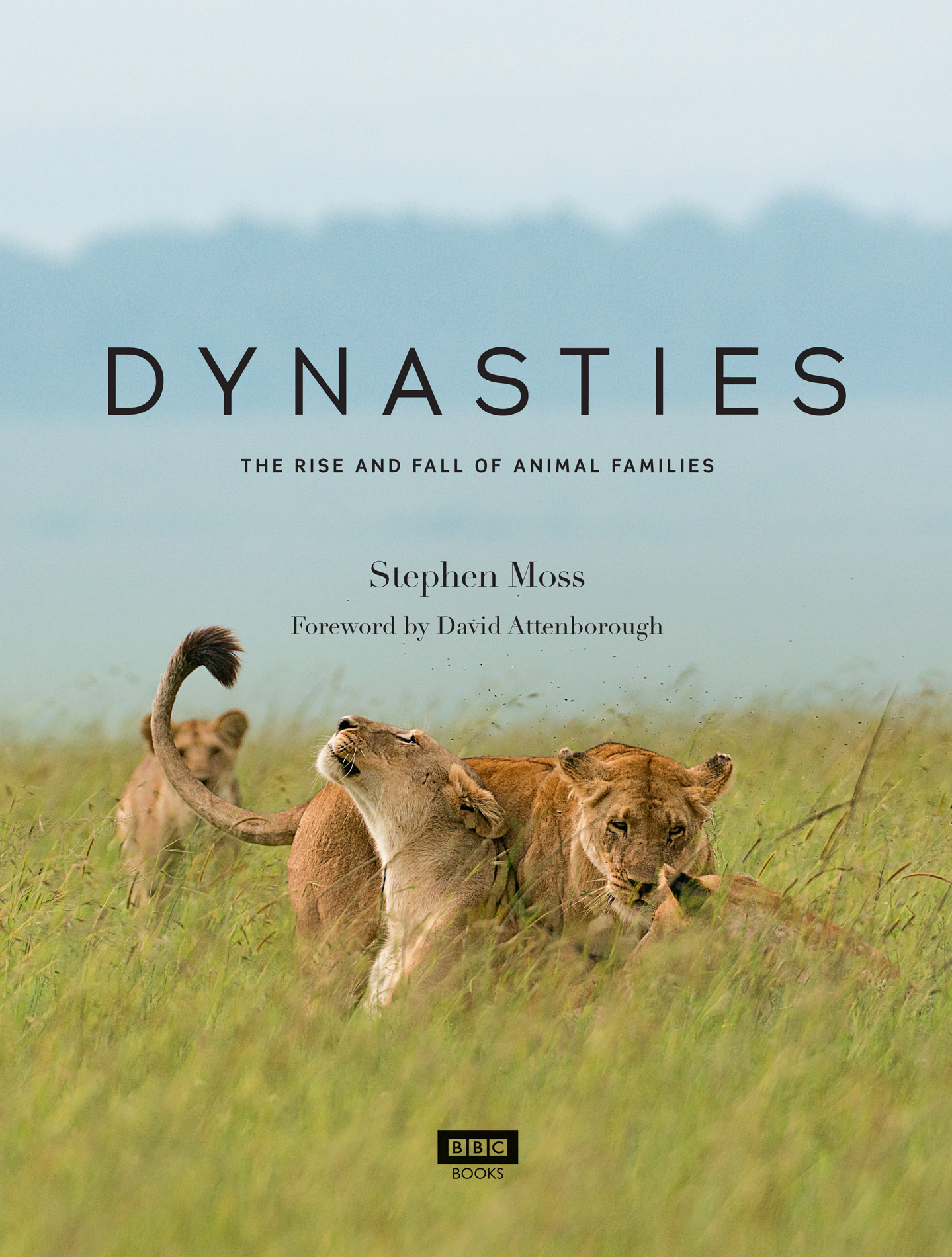

Some degree of anthropomorphism, of course, is justifiable and inevitable. If an elephant, on seeing you, lifts its trunk, flaps its ears and then charges, you are justified, at the very least, in saying that it is angry. That, certainly, is attributing a human emotion to an animal. What other word in our everyday vocabulary do we have to describe its feelings? But suppose you watched an elephant coming across a pile of elephant bones, picking them up with its trunk, one by one, as if caressing them. It would be tempting to say that the animal was mourning the death of a relative tempting, but unjustified. Even if you know that the bones had belonged to a member of that elephant family, you could not be sure of what was in its mind. Calling this book, and the television series on which it is based Dynasties might in itself seem to be sinfully anthropomorphic. It will, after all, remind many of the famous American television series, Dynasty, which ran for many years about a human oil-rich family in the United States whose interpersonal relationships were so sensational and so fractious. Happily, however, the dictionary legitimises such use, for it says no more than that the word refers to a succession of rulers of the same line or family. Animals have families, just as we do, and that is exactly what this book, like its parent series, is about.

Sir David Attenborough with the pack of painted wolves, one of Africas most sociable animals.

To choose their subjects, the producers consulted ethologists all round the world, asking whether the particular animal group they were studying was itself approaching one of the crises which inevitably overtake even the most amiable and well-established families. From the answers, they selected five, as varied as possible both in the nature of the animals themselves and the sort of dramas that were likely to overtake them. Camera teams then joined the scientists and followed the fortunes of each of those families for up to two and a half years.

It was a risky plan. It could be that in spite of the ethologists predictions, nothing dramatic would happen, that the animals concerned, day after day, month after month, would continue doing exactly the same sort of thing, without any radical change. In such a case, even though they were filmed over such a long time, there would be scarcely enough incidents to justify an hour-long programme. It might also be that a crisis would lead not to happier times with a new generation, but a failure of the animals concerned to meet the demands of their new situation. But the producers determined before the series went into production that, once a community had been chosen, the drama would be told exactly as it happened.

You must now be the judge as to whether these varied and extraordinary histories are tragedies or triumphs.

David Attenborough

Helicopter pilot Gert Uys flew all the aerials of the painted wolves, including some remarkable manoeuvres filming Sir David Attenboroughs introduction.

SOFT RAIN FALLS across the plains of Kenyas Masai Mara, soaking trees, grass and every living thing in its path. Little groups of vultures hunch beneath the broad canopies of acacia trees, seeking shelter from the steady downpour. Giraffes and zebras, impalas and gazelles, buffaloes and wildebeest, stand around in loose herds, always alert to any danger. And hidden in the long grass beneath an acacia tree, out of sight of all but the most acute observer, a lion waits patiently for the rain to stop. Her name is Charm, and she is a mature, experienced female, the leader of her pride.

A typical lion pride usually contains between 12 and 15 lions: several adult females (normally sisters or cousins), along with between two and four adult males and their offspring, which range in age from newly born cubs to adolescents between one and three years old. However, some prides may be far bigger, with up to 30 (and in one instance, in South Africas Kruger National Park, almost 50) animals in all. Territory size varies too: where food is plentiful, as here in the Masai Mara, it may be as small as 50 square km (20 square miles); but in dry areas it can be as large as 2,000 square km (roughly 800 square miles).

All other big cats are essentially solitary animals, the lion being the only one that habitually lives in a larger social group, whose members help one another both by hunting together and by safeguarding the cubs. So the pride is subject to complex rules, to ensure that it remains stable and sustainable.

Typically, the most mature female like Charm leads a lion pride. The younger females, who between them keep the pride fed and look after the cubs, then support her. The males, in turn, keep the females and youngsters safe. So although at first sight the bigger, stronger and more impressive-looking males appear to be in charge, the reality is rather different.

But Charms pride was far from typical in that it had no fully mature males. When the team began filming, there were just ten lions in the Marsh Pride, all of which were related to Charm, and so formed part of her dynasty. As well as her cousin Sienna, Charm had four offspring: three-year-old male Tatu, the lion equivalent of a teenage boy, and her eldest daughter Yaya, likewise three years old; and two younger ones a male, Alan, and a female, Alanis. Sienna also had four: her three-year-old son Red, Tatus constant companion; and one younger son and two daughters from a later litter. But none of the males was yet old or experienced enough to do the duties expected of mature males.

Next page

Sir David Attenborough with the pack of painted wolves, one of Africas most sociable animals.

Sir David Attenborough with the pack of painted wolves, one of Africas most sociable animals.  Helicopter pilot Gert Uys flew all the aerials of the painted wolves, including some remarkable manoeuvres filming Sir David Attenboroughs introduction.

Helicopter pilot Gert Uys flew all the aerials of the painted wolves, including some remarkable manoeuvres filming Sir David Attenboroughs introduction.