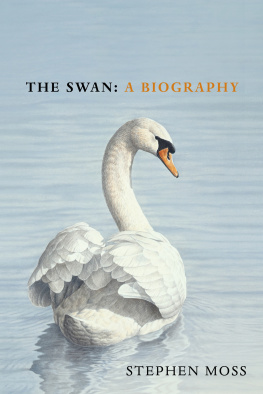

Stephen Moss

THE SWAN

A Biography

VINTAGE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published by Square Peg in 2021

Text copyright Stephen Moss 2021

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Jacket: (front) watercolour by Simon Turvey Medici/Mary Evans; (back) Christmas card The David Pearson Collection/Mary Evans; spine and inside flap courtesy of Biodiversity Heritage Library

Endpapers courtesy of Getty Images

Author photograph Graeme Mitchell

ISBN: 978-1-473-58712-0

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

To my mother, Kay Moss, who first took me down to the riverbank to feed the swans

Swan

Feathersung in blue,

you coast liquid holloways,

great wings nested.

Bone beaked and archaic,

you drift down skywaters,

cloud maps circled in your eye.

Sun winks and

galaxies explode about you.

Starfields of tiny lights

cloak you in constellation.

You are this rivers dreaming,

sun coins strewn

at your breast.

Ruth Lawrence

Prologue

The mute swan is Britains largest bird and one of the worlds heavier flying animals. It is as familiar to most people as the robin. It is graceful, confiding and much loved.

Janet Kear, The Mute Swan (1988)

When I first hear the sound, somewhere in the far distance, it doesnt seem to be made by a bird at all. A regular, rhythmic series of huffs and puffs, as if someone is overdoing their exercise regime, or fanning a fire with a set of old-fashioned bellows.

I look up into the wide, blue Somerset sky as two huge, white birds fly low over my head, before heading away towards the horizon. A pair of mute swans, contradicting their name. The sound I can hear is not, however, made vocally, but by their wings, as they beat them in a steady rhythm through the air.

This phenomenon is not easy to capture in words, as the ornithologist David Bannerman notes in The Birds of the British Isles:

The noise made by the air passing through their great wings produces, as the Handbook puts it, a musical humming throb difficult to describe, but very distinctive and audible for a considerable distance.

While on a visit to Abbotsbury Swannery in Dorset, described in his 1983 book The Kingdom by the Sea, the American author Paul Theroux chose a more graphic description:

I heard a sound two sounds a rapid sawing, a high muffled hee-haw, like the harsh hum of silk being woven in a clapping loom. It came closer, strengthened to a kind of breathing, though I could not place it. I listened and looked sharp, and I saw two huge swans flying low over the Fleet, beating their wings, tearing the air with them When they were directly overhead, they sounded like two lovers in a hammock.

But whatever image the sound conjures up, it is certainly impressive: given the right atmospheric conditions, flying swans can be heard from more than a mile away. Just like more conventional bird songs and calls, this is a communication tool: helping the birds stay together when airborne, especially when it is dark or foggy. For us earthbound mortals, it draws attention to a creature we are never likely to ignore: the largest, heaviest, and arguably most familiar, British bird.

Along with the robin, and domestic creatures such as the goose and chicken, swans are one of those birds that seem to have been in our lives forever. From our earliest memories, when we were taken to the park to feed the ducks, these huge (and to a small child, frankly terrifying) creatures have embedded themselves deep inside our consciousness.

In lowland areas of Britain, where the vast majority of us live, swans are a more or less constant presence, as Bannerman notes: The mute swan in these islands is almost a part of the countryside, for wherever one may be in rural England a pair of them is almost sure to be in possession of the village pond or nearby lake.

In towns, cities, villages and the wider rural landscape, wherever there is a stretch of water for them to find food and make their nest, you will come across swans. From village ponds to city park lakes, along narrow streams and broad rivers, and from grassy fields to coastal estuaries, they are almost everywhere.

Unlike other birds which, even when common and widespread, are often shy and elusive, swans are not just ubiquitous, but also very easy to see. Thats partly down to their bright white plumage, but also because of their huge size: an adult male swan is almost twenty times as long, and over 200 times as heavy, as our smallest bird, the goldcrest.

Their large size also means that swans simply dont fear humans, at least in the way that most other birds do. This does, however, have its downsides: as we shall discover, swans are surprisingly vulnerable to deliberate or accidental injury and death. So while at first sight swans may appear to be invulnerable, their lives are often marred by these violent, and sometimes fatal, encounters.

The ubiquity of swans has created a host of myths and legends about them: some going back to ancient civilisations, others far more recent in origin.

Swans habit of mating for life or at least until one of the pair dies, after which the survivor will usually seek out a new partner has led to them being closely linked with love, fidelity and purity (because of their whiteness). This, in turn, has inspired writers down the ages to create countless stories and works of art about them, from the Ancient Greek tale of Leda and the Swan to Tchaikovskys ballet Swan Lake.

There are modern myths about swans, too: that they are completely silent (they arent); that they all belong to the Queen (they dont); or that a single blow of a swans wing can break a mans leg or arm (it really cant).

As I showed in my previous biographies, The Robin, The Wren and The Swallow, there is often a clear connection between the behaviour of the real, biological bird and its cultural counterpart: put simply, their habits frequently give rise to their mythology and folklore. And like robins, wrens and swallows, swans have a very special place in our affections.

Just as with the robin, whose attacks on rivals can be vicious and even deadly, the way we view the swan as a symbol of love and purity is often at odds with its day-to-day behaviour. Although they cannot actually break a human limb with a single sweep of their wing, they are known to be aggressive towards any other creature including human beings that dares to venture too close to them or their young. Being confronted by a male swan, hissing and opening its wings to look as big and scary as it can, is a pretty alarming experience. As we shall discover, the swan is a more complex, and less benevolent, creature than we might first assume. As the eminent ornithologist and swan expert Christopher Perrins rightly points out, not everybody likes swans.