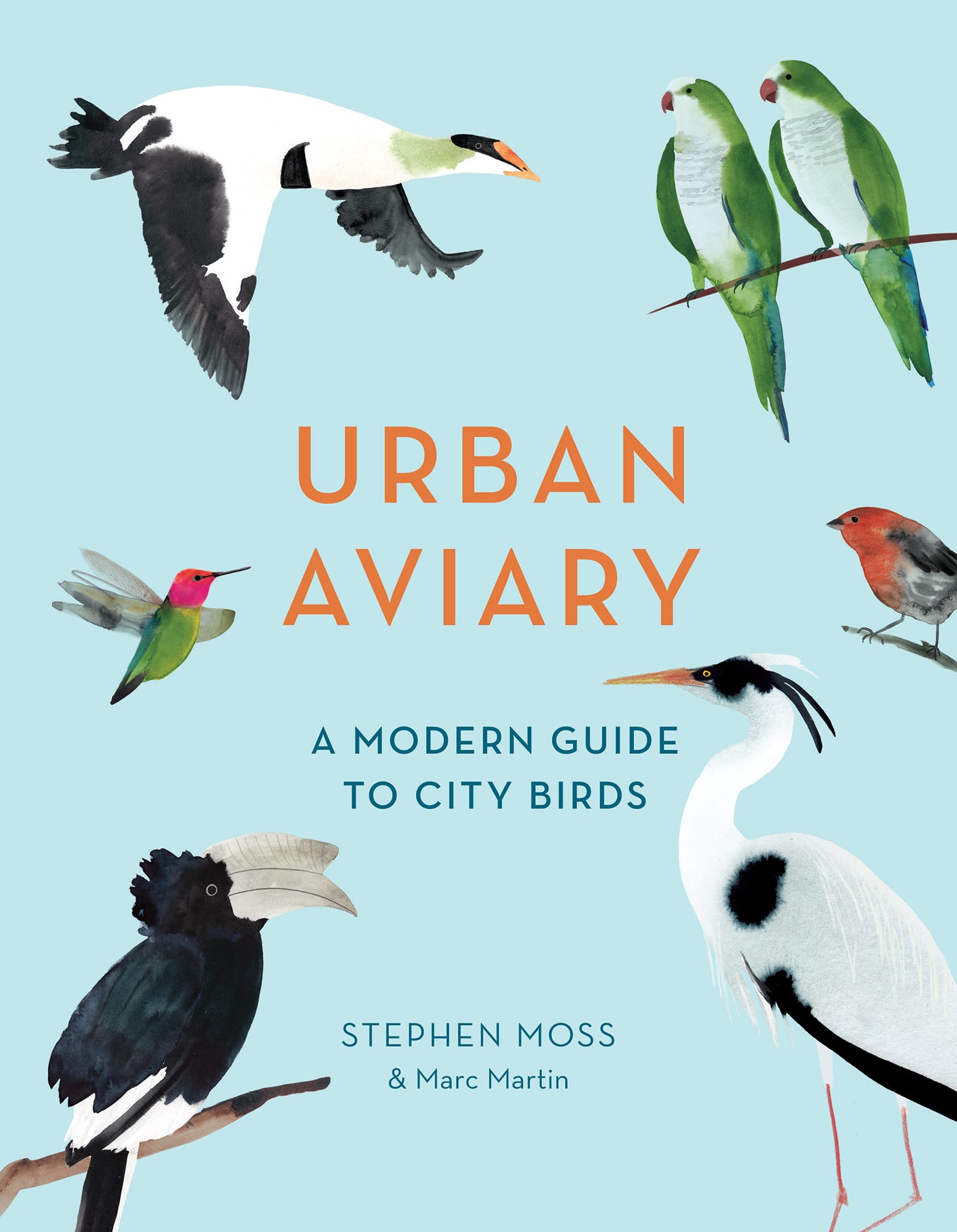

URBAN AVIARY

A MODERN GUIDE TO CITY BIRDS

STEPHEN MOSS

and Marc Martin

INTRODUCTION

At first sight, the phrase Urban Jungle suggests a bleak, lifeless, dystopian environment like the one portrayed in the film Blade Runner. Less dramatically, it is also perceived as a dull, grey, concrete city filled with drone-like commuters, travelling to and from their places of work.

Try looking at the phrase in a different way, however. If you take it literally, rather than metaphorically, then it begins to make sense. Thats because many towns and cities around the world have become a haven for a wide range of wild creatures that have adapted to life alongside us in new, different and unexpected ways.

Think about this a little longer, and you will realise that a city can provide everything wildlife needs for survival. There is plenty of food either accidentally or deliberately provided by us. There are sources of water and places to roost, shelter and breed. In temperate regions, cities tend to be several degrees warmer than their surroundings, particularly in winter. This effect has led to cities being described as urban heat islands, and allows the breeding season to get off to a head start.

No group of animals is more visible, ubiquitous or easier to see than birds. From the smallest hummingbirds to some of the largest birds on the planet, such as swans and ostriches, many birds have adapted to urban life. While this includes species we might expect crows, gulls and pigeons, for example there are also some real surprises.

Half a century or so ago, when the peregrine was threatened by poisoning and persecution, who would have imagined that the fastest creature on the planet would later become a regular resident in the centres of Barcelona, London and New York? Who expects to see hornbills in Kampala, turkey vultures in Washington, DC or the wrybill, one of the worlds rarest waders, in Auckland?

From frigatebirds soaring over Rio de Janeiro to bowerbirds displaying in the suburbs of Canberra, from penguins in Cape Town to pelicans in San Francisco, and from flamingos in Montpellier to huge flocks of starlings roosting around the Colosseum in Rome, a remarkable array of avian sights, sounds and spectacles are to be found in the worlds cities. Birds have adapted to urban life, too not least the crows of Tokyo, which use passing traffic to crush the shells of nuts so they can get at the food inside.

Today, more than half of the worlds population makes its home in cities; by 2050, projections suggest that there will be close to ten billion people on our planet, and two-thirds will live in cities. In the industrialised West, the proportion is even higher: whereas in the year 1800 just one-fifth of Britons lived in towns and cities, today that has risen to over ninety per cent. The figures for China read just as dramatically, from just one in seven people in 1950 to close to half today. Even in the United States, often regarded as more rural in character than much of Europe, more than four out of five people are city dwellers.

This has crucial implications for the future of both birds and ourselves. If we welcome birds into our cities, by providing food, water and places to nest, we will benefit too. All the evidence shows that regular contact with nature improves our physical, mental and emotional health. If we shut out the birds, pushing them to the fringes and eventually providing nowhere for them to live, we will lose out as well. Its a simple choice.

For the past decade or so I have lived in Somerset, in the heart of the English countryside. But for the first half of my life I lived in and around London, where, as a child, I first discovered the wonders of birds.

Since then, I have travelled to all six of the worlds inhabited continents, and enjoyed memorable days birding in cities from Lima to Reykjavk, Sydney to Seville, and Barcelona to Buenos Aires. That has given me a special love of urban birds, including many of the species I have chosen to include here.

This book aims to provide city dwellers around the world with a guide to some of the most extraordinary species of birds that live alongside them. By showing how these birds dont just survive, but thrive in our cities, I hope to encourage people to appreciate them, and welcome them into their busy lives.

STEPHEN MOSS

KEY

average length

average length

average wingspan

average wingspan

average weight

average weight

Note on measurements

Measurements given in each entrys statistic box are the combined male and female average figure for a fully grown, adult bird. The length measurement for each entry is the distance from the tip of the beak to the tip of the tail. The wingspan measurement for each entry is the distance between the tips of the longest primary feathers on each wing when outstretched.

ANNAS HUMMINGBIRD

Vancouver, Canada

10.5cm (4in)

10.5cm (4in)

12cm (4/in)

12cm (4/in)

4.5g (/oz)

4.5g (/oz)

The election resulted in a landslide, with the winner taking over forty per cent of the vote, easily beating her three rivals. This poll, held in the Canadian city of Vancouver in May 2017, wasnt won by a human candidate, but by a bird: Annas hummingbird.

This tiny creature, weighing just 4.5g (/oz) on average, and only 10.5cm (4in) long, was named the city of Vancouvers official bird, in an online vote, beating the spotted towhee, varied thrush and northern flicker (a kind of woodpecker).

It certainly merits its win. Like all hummingbirds, this is a jewel-like creature, with iridescent feathers that sparkle and gleam as the bird turns towards the light, producing a flash of bright emerald. In spring and summer, the male develops a magenta head, face and throat, with a white flash through his eye.

It may come as a surprise that any hummingbird a family usually associated with the tropics of South and Central America would venture this far north at all. Yet Annas is just one of several species that breed up the west coast of the United States and Canada, having spread north from California since the 1930s. And now, in a major change of habits, Annas hummingbirds have begun to winter in the northern parts of their range including Vancouver.

This is partly down to the urban heat-island effect (see ). But, here, it is also because Vancouvers citizens lend a helping hand to these tiny birds, putting out sugar water on which they feed, and making sure that this doesnt freeze during cold spells. The planting of nectar-rich flowers some of which bloom in winter has also helped the hummingbirds survive.

average length

average length average wingspan

average wingspan average weight

average weight