And out of the ground the Lord God formed every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air; and brought them unto Adam to see what he would call them: and whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof. And Adam gave names to all cattle, and to the fowl of the air

Genesis, 2:19-20

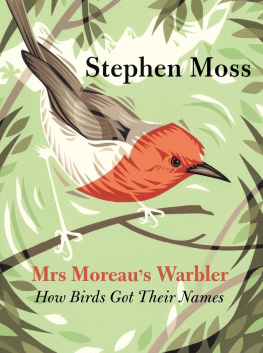

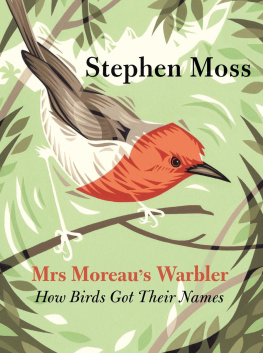

Swallow and starling, puffin and peregrine, blue tit and blackcap. We use these names so often that few of us ever pause to wonder about their origins. What do they mean? Where did they come from? And Old Testament mythology aside who originally created them?

Sometimes its easy to assume that we know what a birds name means, and often that assumption is quite correct. Treecreepers creep around trees, whitethroats have a white throat, and cuckoos do indeed call out their name.

The origin of other names can seem obvious, but may not be quite as straightforward as first appears. Even the simplest of English bird names, blackbird, turns out to be more complicated than you might imagine. There is also a whole range of folk names, from scribble lark to sea swallow and flop wing to furze wren, each of which has its own tale to tell about our language, history and culture.

*

Another pressing question is, when were birds given their names? Broadly speaking, it is reasonable to assume that most common and familiar birds were named a long time ago, by ordinary people hence the term folk names while scarce and unfamiliar birds were named much more recently, by professional ornithologists.

Another general rule is that most early names were based on some obvious feature of the bird itself: its sound, colour or pattern, shape or size, habits or behaviour. Some of our longest-standing names reflect this, such as cuckoo and chiffchaff, blackcap and whitethroat, woodpecker and great tit.

Once the professionals got involved, from the seventeenth century onwards, names began to be based on more arcane aspects of birds lives, such as where they live or the locality where they were found. These include habitat-based names such as reed, sedge and willow warblers, along with place-based names such as Dartford warbler and Manx shearwater. Many compound names, such as black-tailed and bar-tailed godwits, and pink-footed and white-fronted goose, also arose during this period, to help tell similar species apart.

The final category of bird names most of which also originated fairly recently, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is in many ways the most beguiling. These are the species called after people, such as Montagus harrier, Bewicks swan, Cettis warbler and Leachs petrel.

The stories behind these birds, and the people after whom they were named, are told in Chapters 4 and 5. They include the country parson Gilbert White, author of The Natural History of Selborne; James Clark Ross, a young midshipman who shot his eponymous gull on a failed expedition to reach the fabled North-West Passage; and the disgraced military officer George Montagu who, following a midlife crisis, fled to Devon with his mistress, where he pursued the study of birds for the rest of his days.

*

According to the opening book of the Old Testament, once Adam had been created, almost the very first thing he did was to give names to the birds. As one commentator has shrewdly pointed out, this means that more dubious claimants aside taxonomists can justifiably claim to be the worlds oldest profession.

Since then, names have always fascinated us, yet they can also frustrate us. In Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeares lovelorn heroine laments,

Whats in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet.

Superficially at least, the Bard makes a valid point. As philosophers have long argued, the name we give to a person, place or object often has little or no connection with its sense and meaning: if we called a rose something completely different, it would still be the same flower.

But is that always the case? After all, names are not always random or meaningless labels, unconnected with the object to which they are attached. More than any other words, names carry with them the baggage of their etymological history: a history that, once we begin to investigate more deeply, reveals unexpected origins, and often yields a profound association between the name and the object that bears it. Thats certainly true of onomatopoeic names, which derive from the sound the bird makes, and also of many names based on a birds colour, pattern, habits and habitat.

At other times, though, a birds name can cause confusion and misunderstanding. Some lead us down a blind alley, as in hedge sparrow long used for the dunnock which is not a sparrow at all, but an accentor. Other misleading names include stone curlew, a bird only distantly related to the true curlews; and bearded tit, which is neither bearded (it sports magnificent moustaches), nor a tit.

In an ideal world, the names we give to birds would all make perfect sense. But in the real and far more fascinating world, they do not. This is for one simple reason: they were not handed down to mankind since time immemorial, as depicted in the Book of Genesis. Instead, they were coined by a whole range of different people, over many thousands of years, from the prehistoric era to the present day.

For this pressing urge to name the things we see around us dates back to our earliest ancestors. Initially, at the dawn of human civilisation, it would have been for purely practical reasons. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors would have soon realised that they needed to give names to the various wild creatures they came across, so they could easily distinguish between those that might be good to eat, and those that might kill and eat them.

As the evolutionary biologist Carol Kaesuk Yoon has pointed out, the ability to name things and then recall what they were named at a later date would have been essential for survival: Anyone living in the wild who could not reliably order, name, communicate about, and remember which organisms were which who could not do good caveman taxonomy would most likely have led a considerably tougher and possibly shorter existence.

From roughly ten thousand years ago, the coming of agriculture brought a new dimension to the naming of living things. Those first farmers needed to know when a particular wild flower would come into bloom, or at what time of year a migratory bird would depart and return. Understanding the timing of these events allowed them to chart the changing of the seasons, and know when to plant and harvest their precious crops.

As a result of these primordial needs, human beings evolved to notice the plants and animals around them, perceive their similarities and differences, and give them names based on those characteristics. Indeed, had our ancestors not learned to read the natural world, and shape that world around their needs, it is unlikely that human society and culture would have made such rapid and spectacular progress.