Pagebreaks of the print version

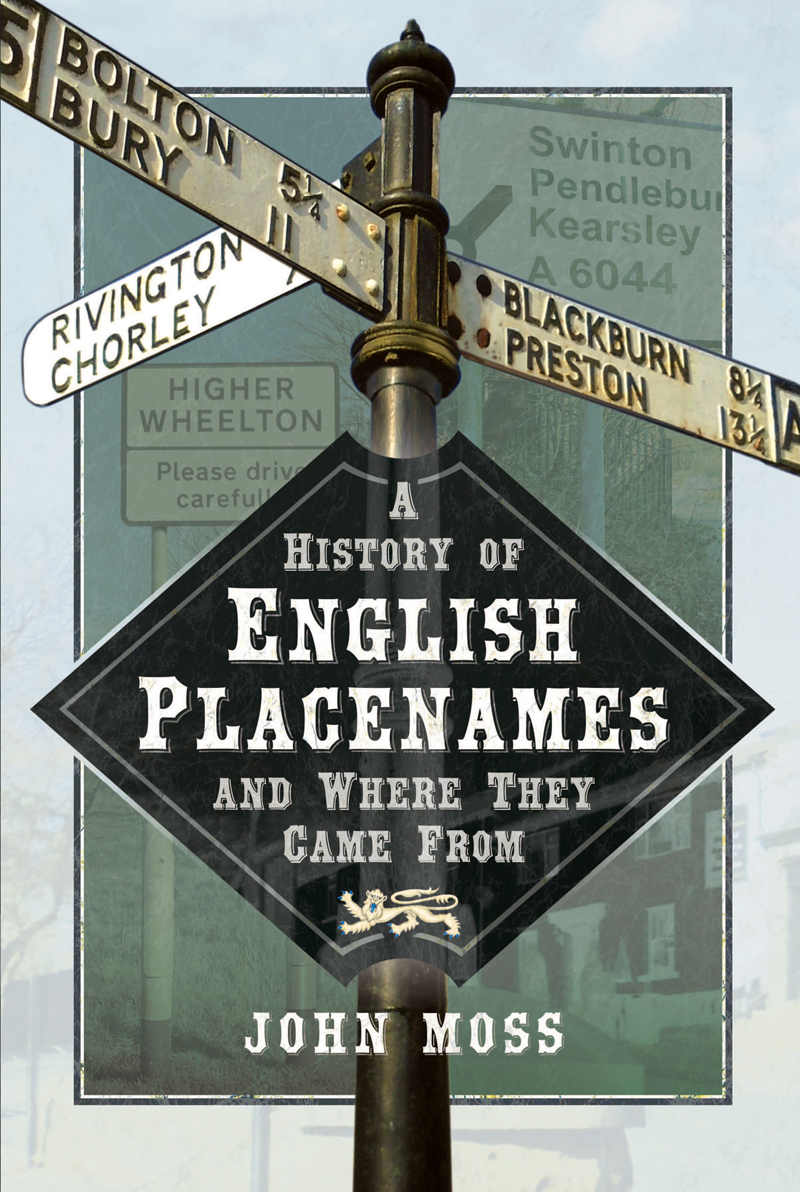

A HISTORY OF

ENGLISH PLACENAMES

AND WHERE THEY CAME FROM

We do not make history history makes us

Martin Luther King

A HISTORY OF

ENGLISH PLACENAMES

AND WHERE THEY CAME FROM

JOHN MOSS

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright John Moss, 2020

ISBN 978 1 52672 284 3

eISBN 978 1 52672 285 0

MobiISBN 978 1 52672 286 7

The right of John Moss to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Foreword

In my earlier book, Great British Family Names and Their History, I wrote that while many families are named after places, some placenames come from the people who founded them. It seemed logical, therefore, that this book would follow, and that while it comes from a more-or-less opposite direction, it complements the first, bears out the original premise and completes the picture.

This is a book about the derivation of many English cities, townships, villages and hamlets placenames whose origins lie shrouded in history; names that come from the days when Celtic tribes occupied these islands and were later overtaken by Romans, Angles, Jutes, Danes and Saxons, as well as the Norman French invaders of 1066. These immigrant cultures were all assimilated, and from them emerged the common placenames we recognise today, even though the passage of time may have obscured their origin.

I began this project after taking early retirement, at a time before online resources were commonplace. My research entailed many months spent in Manchester Central Library, making copious long-hand notes. In those days there were no smart phones, laptops or tablets my well-worn Schaeffer fountain pen, a pot of black ink, a notebook and the empty silence of a library full of books were the only resources at my disposal.

I found several printed publications of particular value, and I have made great use of them. First, William the Conquerors Domesday Book, sometimes referred to as the of 1086, originally called The Book of Winchester, and specifically the excellent complete translation of the survey by Dr Ann Williams and Professor G.H. Martin. This immense resource is the ultimate reference work and my book would have been almost impossible to complete without it. Second, I must mention Anne Savages scholarly translation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles , which offered essential information regarding anything pre-dating the Norman Conquest. A.D. Mills Dictionary of British Placenames also proved a most useful starting point, in its comprehensive, if brief listings of over 17,000 places in Britain.

Then, given the profusion of material now in the public domain, thanks to the exponential growth of online resources, I feel obliged to make a passing reference to the Internet. While its factual information is voluminous and its accessibility has enabled almost anybody to publish anything, no matter how trivial or fatuous, the veracity of much of its content is frequently dubious, trivial or erroneous. The reader should tread warily and guardedly, and the maxim should always be let the reader beware.

It is a fortunate and convenient fact that nowadays almost every town, city, village and in England has its own website, as do most local history societies, each extolling the pride and virtue of their particular place. These have proved an invaluable boon and I have found that, for the most part, they are rich veins of trustworthy information. This is particularly true of official local authority and council websites, who have direct access to their community records of history, charters, grants and foundations, and I have used some of these sources in compiling this work.

The interpretation of the meaning of English placenames is not an exact science. Often there are several possibilities as to an exact translation, especially when dealing with old Saxon words, many of which were not written down, or if they were, it was at a time before the English language, as we understand it, was formally fixed. This being so, it is not surprising that spellings vary and explanations of name derivations differ from one authority to another. This is to be expected; ancient placenames are often ambiguous and it is impossible to be absolutely certain of their true meaning or origin, so that a fair amount of educated guesswork as well as traditionally accepted interpretations are called upon to make sense of them.

Many medieval words have long fallen out of common usage and their significance is almost lost. This is particularly true of land measurements referred to in the Conquerors survey of 1086, where the meaning of ancient words like carucate, hide, bovate and sokeland are lost to most contemporary readers. In an age before measuring tapes and rulers existed, when the general populace was neither literate nor numerate and precise units of measurement were unknown, such calculations had to be based on rather more subjective criteria. Therefore, I have included a glossary at the beginning of this book in explanation of the most frequently occurring terms.

Of course, there are far too many townships and villages in England to deal with all of them in the degree of detail they might deserve, or to include every possible name. So, what follows is a selection of around 2,000 English placenames a purely personal choice.

As to my definitions, in general terms, for the purpose of this book, I define a town as a fully operational entity with its own council, public services and elected councillors; a village is identified as a suburb of a larger towns local authority which will normally have a church at its centre, and a hamlet as a small collection of dwellings with no church. However, as many great cities began life as small hamlets, I have used the word townships, as a generic term for all such embryonic settlements, no matter how big, small, or important they were to become.

What follows, therefore, are some of the explanations and derivations of many placenames in England. And, while much of the material that I have included may be available elsewhere, in this book I have attempted to produce a valuable, concise and eminently readable reference document.