Kenneth Mellanby, C.B.E., Sc.D.

S. M. Walters, M.A., Ph.D.

PHOTOGRAPHIC EDITOR

Eric Hosking, F.R.P.S.

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader in the wild life of Britain by recapturing the inquiring spirit of the old naturalists. The Editors believe that the natural pride of the British public in the native fauna and flora, to which must be added concern for their conservation, is best fostered by maintaining a high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of exposition in presenting the results of modern scientific research.

THE aim of the New Naturalist series is to interest the general reader in the wildlife of Britain. As over 80 per cent of the surface of this country is farmed in one way or another, the majority of New Naturalist books have been at least partly concerned with the effects of agriculture on our wild animals and plants. This is particularly true of the late Sir Dudley Stamps Man and the Land, the late Sir John Russells The World of the Soil, Dr Ian Moores Grass and Grasslands, my own Pesticides and Pollution, the late Dr R. K. Murtons Man and Birds and, perhaps most significantly, Hedges by my colleagues Drs E. Pollard, M. D. Hooper and N. W. Moore.

As the series already covers the subject of farming and wildlife so substantially, readers may wonder why this further volume is thought necessary. I believe that it may be valuable to consider, in one volume, the ways in which modern farming is changing our countryside and the wildlife of that countryside. I have tried throughout to concentrate on the effects of agriculture as it is practised in Britain in the second half of the twentieth century.

I could not have attempted to write this book had I not been so fortunate as to have had unique opportunities to see, at first hand, the problems of both farmers and conservationists. I was for over six years head of the Entomology Department at Rothamsted Experimental Station, the worlds senior agricultural research station. Then, in 1961, I joined the staff of the Nature Conservancy, on appointment as the first Director of Monks Wood Experimental Station, where the emphasis was on conservation, but where the effects of pesticides and changing farming practices on wildlife were investigated. I have thus had the opportunity of working with colleagues who have been closely involved with my subject. Thus lowland grassland was the main interest of the team led by Dr Eric Duffey; he has edited an authoritative book Grassland Ecology and Wildlife Management which has proved a valuable source of information on this subject. Dr Norman Moore was head of the Pesticides and Wildlife Section, and he also organised the Nature Conservancys Agricultural Habitat Team, which contributed substantially to my subject. Then I have lived for twenty years in the most intensely farmed arable area of Britain, and have had the opportunity of discussing their problems with farmers and land owners throughout the country. So I hope that I have been able to understand the point of view of both farmers and conservationists.

It would be idle to deny that there has been considerable conflict between the two groups. As I show, most recent developments in farming have been harmful to our wild plants and animals. Rare species have become rarer or extinct, and even common varieties may no longer be present for the enjoyment of the public in many parts of the country. On the other hand many conservationists have shown little understanding of the real difficulties of farmers, and have given them no help in overcoming these problems. Fortunately there is now a growing movement to bring the two sides together, to which I hope that this book will make some contribution.

In common with other books in this series, I have used common English names for plants and animals where these are generally accepted. I have also given the Latin name on the first occasion on which a species is mentioned. I have tried always to use the most generally accepted Latin names, relying for instance on The Flora of the British Isles by W. R. Clapham, T. G. Tutin and E. F. Warburg for flowering plants, and for insects I have used A Check List of British Insects and other publications by G. S. Kloet and W. D. Hincks. I apologise to any systematists if I have not given any new Latin names which their studies have established; I think that readers will be able to identify the organisms which I mention in my text.

INTRODUCTION

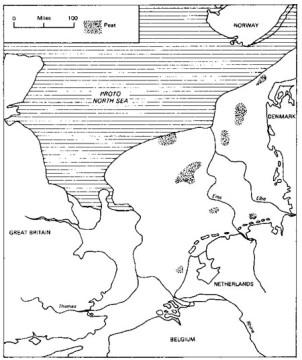

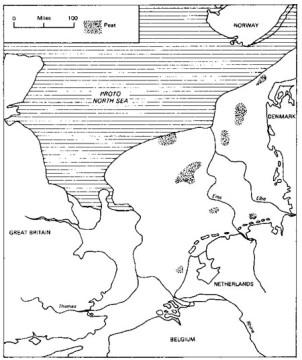

GREAT BRITAIN became an island, separated from continental Europe, some seven thousand years ago, when the level of the North Sea rose and covered what was until then dry land connecting the eastern part of England with Denmark and the Low Countries. At this time almost the whole of the British lowlands was covered with deciduous forest, mainly oak. In the mountainous area conifers took the place of deciduous trees, though the highest mountains were open moorland. Grassland only occurred in small temporary patches where the forest had been destroyed or where trees had died of old age. There were substantial areas of bogs and marshes, and the climate was warmer and wetter than it is today. The flora and fauna consisted mainly of woodland species and those living in marshes and on the sea shore.

At this time Mesolithic man was still a hunter and gatherer making little impact on his environment. His numbers were low, perhaps only a few thousand individuals in the whole country. Then about five thousand years ago Neolithic man invaded Britain, bringing pottery, polished stone implements and arable agriculture. This was when mans influence on the countryside first began to be noticeable. Small fields cleared from forest and scrub were cultivated and corn was grown, but livestock, sheep, goats and cattle, were grazed and extended the areas of grass on the chalk and limestone areas such as Salisbury Plain, the South Downs, the Yorkshire Wolds and the Cotswolds. Mans numbers grew as his food supply increased, and farming methods became more sophisticated with the successive invasions of Bronze Age (2,000 B.C. to 500 B.C.) and of Iron Age people (500 B.C. to 40 A.D.). By the time of the Roman occupation of 43 A.D. there were probably half a million Britons, and farming in the southern part of the country was so successful that wheat was exported to what is now France. Woodlands still covered most of the country, marshes and fens were undrained, but there were substantial areas of open fields with cereal crops or grass for grazing livestock.

During the period of the Roman occupation and the unsettled centuries between the withdrawal of the legions in 383 A.D. and the Norman conquest, farming continued to develop. The Saxons are generally credited with the introduction of the heavy ox-drawn plough which enabled heavy clay soils to be brought into cultivation. More of the forest was removed, and the first hedges grew up to divide fields and parishes. Grazing cattle, by preventing woodland regeneration when they ate tree seedlings or trampled them with their hooves, contributed to the spread of grasslands and to their own food supply. The human population increased slowly with the improving agriculture, reaching about one million by 1000 A.D.