The best nature writer working in Britain today. D AVID C RAIG , The Los Angeles Times

Enthralling and often strident. The Observer

The writing is glowing and compelling. The Countryman

Jim Crumley soars with eagles and we watch with our mouths open, not just because the presence of the eagle fills us with awe but the virtuoso writing does, too. P AUL E VAN , Countryfile Magazine

Well-written elegant. Crumley speaks revealingly of theatre-in-the-wild. Times Literary Supplement

Crumleys distinctive voice carries you with him on his dawn forays and sunset vigils. S IR J OHN L ISTER -K AYE , Herald

Precise and resonant phrase-making Crumley is quite exceptional. J IM P ERRIN , The Great Outdoors

Crumley conveys the wonder of the natural world at its wildestwith honesty and passion and, yes, poetry. S USAN M ANSFIELD , Scottish Review of Books

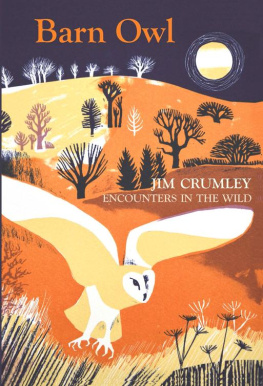

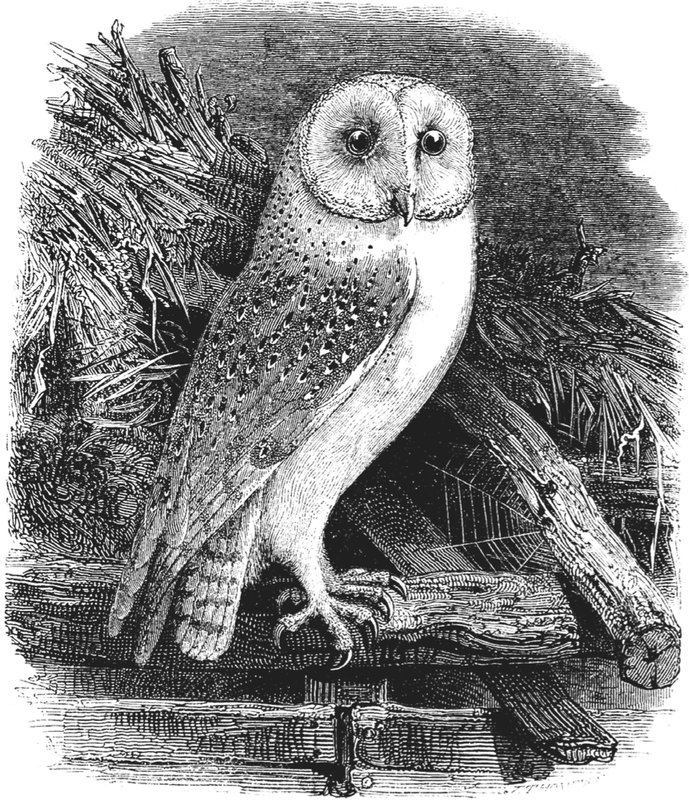

I WAS VERY YOUNG when I understood why a heart shape symbolises love. It was the shape of the fair face of barn owls and I loved barn owls.

Prefab childhood in 1950s Dundee was essentially lived more out of doors than in. The prefabs were neatly buttoned to a west-facing hillside along the last street in town, and the farmland of Angus began across the road. Fields were as much for playing in as growing crops. From the top of the highest fields the land fell away northwards and rose again to the promise of the Sidlaw Hills. I considered winter geese and spring and summer skylarks to be as much my neighbours as my fellow prefab-dwellers ever were.

The entrance to the farmyard was no more than a quarter of a mile away from our prefab, but it was forbidden territory, and inhabited by what Lewis Grassic Gibbon would have called coarse brutes. Thinking about it now, they must have been simply people who did not know how to get on with the non-farming neighbours surrounding them on three sides. I hid when I saw them coming, though it does me no good to admit it now. One of them, only slightly older than myself, once opened a nasty cut in the side of my leg with an astonishingly well-aimed stone.

But the stackyard was a different proposition from the farmyard. I thought of it as no-mans land. It belonged to the farm, of course, and farming things happened there, but it was frontier land that lay between the farmyard and the street from which it was only flimsily fenced off. And mine was the kind of childhood that did not pay much heed to flimsy fences.

Haystacks were shifting, unchancy creatures, especially at night. They seemed to appear overnight then stood around for weeks, or months, and grew dishevelled in gales and downpours. Voles, mice and rats and other furry beasts I couldnt name sped along the curved alleyways between stacks, and barn owls loved voles, mice and rats as much as I loved barn owls, albeit a different kind of love.

So my first barn owls coursed silently through my most impressionable years, low-flying, head-down hunters that tilted and swerved on one wingtip or the other as the light faded over the Tay estuary far below and the lights of villages on its Fife shore glittered in small clusters. The darker the night, the brighter the face, the breast and the underwings of the moping, mopping-up owl, and the more predatory its grip on my young imagination.

* * *

T HE FARM (it seems to me now) was a poor, run-down place with run-down barns, and these are the barn owls favourite kind. Any evening I happened to be walking home that way (and always just a little heart-in-mouth at the proximity of the forbidden territory), there was always the chance of meeting head-on and at close quarters the fair, heart-shaped face of the haunter of no-mans land. These were encounters with nature at the edge of things, the edge of the day and night and the edge of my comfort zone, beyond which the black outline of the farm buildings bleakly inked in my discomfort zone.

* * *

T HE EDGE OF THINGS has since become my preferred terrain the edge of the land, the edge of the sea, islands beyond the edge of the land, the Highland edge and the Lowland edge wherever the two have been in constant collision for well, since the world began, but the last ten thousand years will do for the moment and the sake of argument; wherever the tribes of nature rub shoulders and overlap wherever Highland eyes Lowland and a golden eagle arrows down a fast mile from the first and last mountain to lift a dainty pink-footed goose from the first and last tilting field, the goose deceived into thinking it was just a buzzard until it was much too late; wherever a shoreline-hunting fox might stare out at the ocean with ears forward to catch the cadences of a singing humpback whale.

The barn owl is an ambassador for life on the edge. It is the night owl that also hunts fearlessly by day; the silent flier with a sudden shriek that can shatter glass (and in the brain of a short-tailed field vole it must sound like the shrill anthem of death itself); the restless sentry of the outside edge of the woods with one ear attuned to the grassy banks and the other to the first and last tree shadows; the stone-still embellishment on a country kirkyard gravestone beyond the edge of the village, looking in moonlight like nothing so much as the sculptors final inspired flourish.

* * *

A LL THIS I CAN SEE CLEARLY NOW as a line drawn across the map of my life, a line that began in the stackyard of childhood, although of course the line truly began long before it first crossed my wandering, wondering path, began back on the dwindling edge of the last ice, the edge of the first woods after the ice, the edge of the first settlements along the edge of the first woods, the edge of the first group of stone buildings, the edge of the first farms, stackyards, estate buildings, clock towers that rose purposefully and ticked away the seasons of the centuries until they fell into disuse. It quested among all the new edges of the advance of the people, until, in the late-twentieth and the early-twenty-first centuries the people realised that they could counter the worst side-effects of intensive agriculture, not to mention farmyard renovations and conversions from barns into houses, by building barn owl nest boxes in new metal-roofed barns and in the trees near the edges of new woods and old.

Thus, in the course of one nature writers life, the barn owls capacity for exploiting the edge of things (however and wherever the edge evolves) has allowed it to recover from every setback and to thrive again where less accommodating creatures have succumbed. And because I am a traveller along the edge of things myself, I have been accustomed for much of my life to meeting barn owls along the way.

Those childhood barn owls survive only as a patchwork of memories, memories of glimpses, as unrevealing as moths darting in from the darkness to dance at a flame and vanish again. I remember nothing other than impressions of a few seconds of flight at a time, usually into the insipid glow of street lights, then fading away into the gloom, always fading away into that other world where owl and farmyard conspired to do whatever it was they did together. Except once.

That once was when I was lured by forces beyond my control across no-mans land and into hostile territory, the forbidden world beyond the haystacks. It was the first time I ever saw the owl fly in daylight. It was a sunny early morning of spring although why I might have been near the farm in early morning escapes me now. The owl had appeared among the stacks with its beak clamped round a mouse that hung down from its heart-shaped face like a moustache (a mousetache), and I had not seen