Horace T. Martin, Castorologia

INTRODUCTION

The beaver has a major image problem. A chubby rodent with goofy buckteeth and a tail that looks like it was run over by a tractor tire its no wonder beavers prefer to work under cover of darkness. Theyre ungainly on land and ride so low in the water when theyre swimming that from a distance they can be easily mistaken for floating deadwood.

At best, some might say, the beaver is an icon of insipidness: although often lauded as a paragon of diligence and industriousness, the beaver could just as well be described as a monogamous, workaholic homebody.

At worst, beavers are embarrassing. Not only has their name been co-opted as smutty slang for female genitalia (a usage that first appeared in print in the 1920 s), but theyre also wimps in comparison to charismatic national animals like the American eagle, the English lion and Chinas giant panda.

Unofficially, the beaver has represented Canada since before the country achieved full nationhood. In 1851 , years before Confederation, the Province of Canadas newly independent postal system issued its first postage stamp, the Three-Pence Beaver, which depicted the eponymous animal crouched on a bank beside a cascading stream. But when it came to devising a coat of arms for Canada in 1921 , the beaver didnt make the cut. In the blunt words of Under-Secretary of State Thomas Mulvey, a member of the design committee, It was decided that as a member of the Rat Family, a Beaver was not appropriate. (Actually, beavers belong to their own, exclusive family, the Castoridae, and are only distant cousins of rats and other members of the Rodentia order, but such distinctions probably wouldnt have swayed Mulvey.)

The only reason the beaver eventually gained official standing as Canadas national animal may have been that Americans were threatening to usurp the emblem. Apparently no Canadians had noticed when Oregon, long known as the Beaver State because of its fur-trade history, adopted the beaver as a state mascot in 1969 . When New York announced plans to do the same a few years later, Canada finally asserted its own claim. In 1975 , Parliament passed Bill C-, An Act to provide for the recognition of the Beaver (Castor canadensis) as a symbol of the sovereignty of Canada.

However, a fancy title doesnt guarantee respect. In 2011 , Senator Nicole Eaton stood up in the Red Chamber and called for the beaver to be stripped of its honours and replaced by the polar bear. Canadas symbol of sovereignty was, she said, nothing more than a dentally defective rat and a toothy tyrant that wreaks havoc on farmlands, roads, lakes, streams and tree plantations. Her denunciation hinted at a revenge motive, for she also mentioned her ongoing battle to keep beavers from damaging the dock at her summer cottage.

I have never outright scorned beavers, but I did, for a long time, take them for granted and underestimate their worth. What are you writing about? friends would ask when they found out I was working on a new book. Beavers, Id mutter, in the early days, and change the subject for fear of hearing the word boring in response. Yet I quickly came to realize that beavers arent boring. I just didnt know how fascinating they would turn out to be.

The truth is, the humble and much-maligned beaver is actually the Mighty Beaver, arguably North Americas most influential animal, aside from ourselves. For no less than a million years, and possibly as long as million, beavers in one form or another have been sculpting the continental landscape by controlling the flow of water and the accumulation of sediments filling whole valleys and rerouting rivers, in places. For an equal length of time, theyve also been nudging other species down distinctive evolutionary paths, from trees that have developed defenses against the woodcutters to a multitude of plants and animals that rely on beaver-built environments. Beavers even have an exclusive parasite, the louse-like beaver beetle (Platypsyllus castoris), which spends its whole life roaming through its hosts fur or hiding out in the ceiling of the beavers lodge.

Two things are behind this far-reaching influence: a unique lifestyle and sheer ubiquity. No other animal in the world lives quite like the woodcutting, dam-building beaver. Although eccentric, this way of life is what makes Castor canadensis a classic keystone species that is, the indispensable creator of conditions that support entire ecological communities; an unwitting faunal philanthropist.

Before the fur trade devastated their population, these ecosystem engineers were extraordinarily abundant and prevalent. Picture at least million beavers (or million if the high-end estimate is correct) spread out across almost every part of the continent. At least million dams. And countless biodiversity hotspots beaver ponds, beaver wetlands, beaver meadows all teeming with life. Todays numbers pale in comparison, but beavers are back on the job in many places.

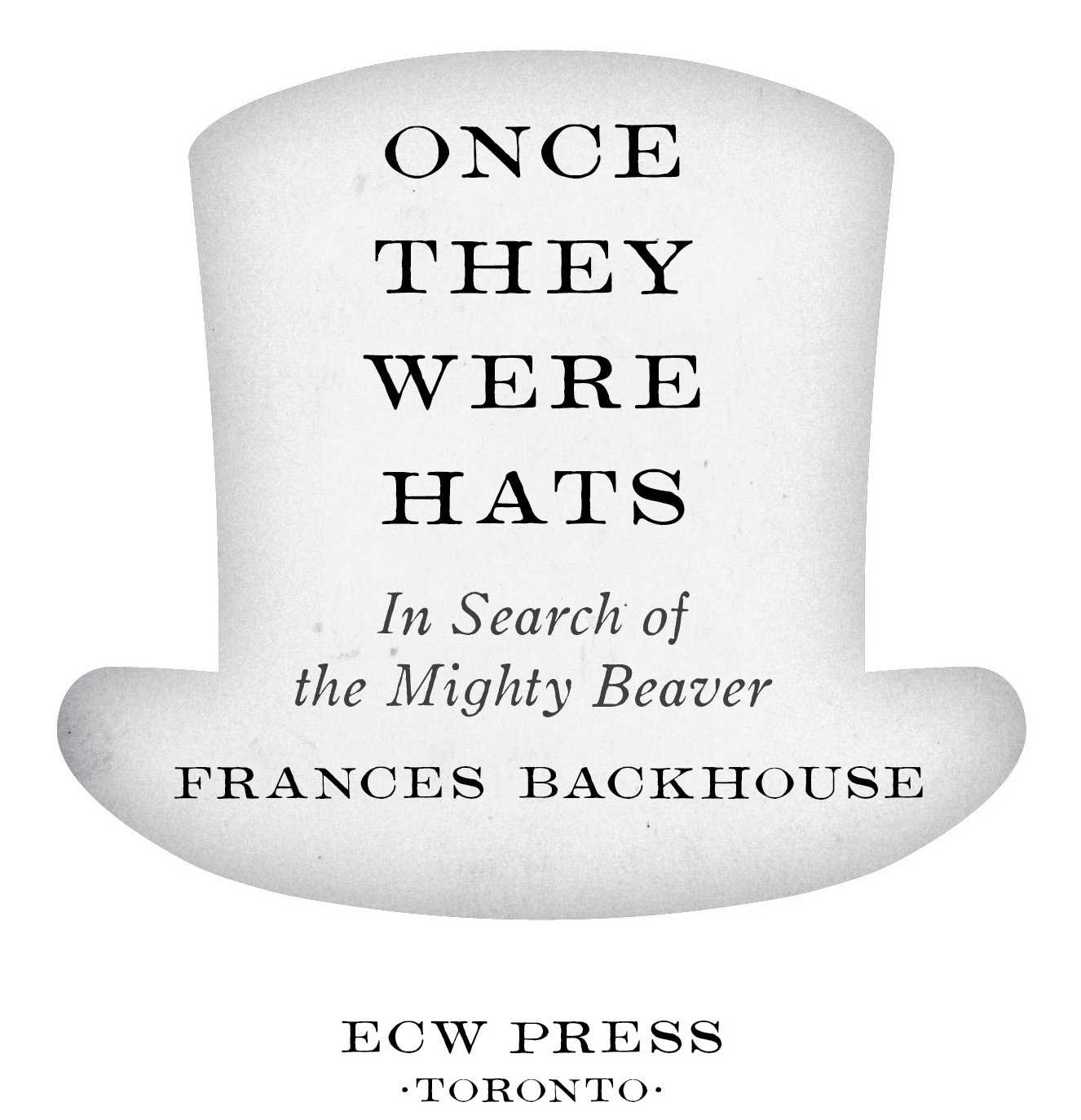

This book is a journey of sorts, one that meanders through the millennia of castorid existence in the company of paleontologists, archaeologists, First Nations elders, historians, hatters, fur traders, trappers, biologists and, of course, beavers. It begins in the watery realm where Castor canadensis once ruled, then plunges back in time to meet the beavers ancient kin, from lumbering giants to pint-sized burrowers. It explores the perspectives of the beavers first human acquaintances, peoples who knew this venerated animal by hundreds of different names, and follows the fur-hungry Europeans who arrived at the close of the fifteenth century and fanned out across the continent in ruthless pursuit of the pelts that were to them like brown gold. After tracing the species nosedive to near extinction and its subsequent revival (one of North Americas most notable conservation success stories), we enter the twenty-first century, where the beaver, so long appreciated mainly for its fur and its legendary busyness, is making a comeback as an ecological hero. Its journey is not over, after all, and there are new vistas ahead on our travels together.

For as long as humans have inhabited this continent, beavers have played a significant role in our lives. They have fed and clothed us, inspired spiritual beliefs and cultural traditions, driven the course of history, lent their name to countless landmarks and kept our water reservoirs charged. Until recently, weve tended to overlook this last contribution, but as we struggle to adapt to the vagaries of climate change, water stewardship may prove to be the beavers greatest gift to us.

kl

.One.

INTO THE HEART OF BEAVERLAND

In 1497 , when the Anglo-Italian navigator and explorer John Cabot landed on Newfoundlands rocky shores and kicked off the European invasion of North America, beavers inhabited almost all of what we now call Canada and the United States, plus a sliver of Mexico. They ranged from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific and from just south of the Rio Grande to the Mackenzie and Coppermine river deltas on the Arctic Ocean. The only off-limit regions were the Arctic barrens, the parched deserts of the extreme southwest and the alligator-patrolled swamps of the Florida peninsula. Otherwise, wherever they could find water and wood, beavers were present.