Contents

Smithsonian Air Disasters Series

Suspenseful stories of tragedy and triumph are brought to life in the Smithsonian Air Disasters television and book series through investigative reporting, official reports, and interviews with the pilots, air traffic controllers, and survivors of historys most terrifying crashes. From the cockpit to the cabin, from the control room to the crash scene, the Air Disasters series uncovers what went wrong and reveals the changes that were made to ensure such disasters never happen again.

Other titles include:

The Flight 981 Disaster: Tragedy, Treachery, and the Pursuit of Truth

Southern Storm: The Tragedy of Flight 242

2018 by Cineflix Media Inc. and Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Based on Air Disasters: Up in Flames, created by Cineflix and shown in the United States on the Smithsonian Channel.

Published by Smithsonian Books

Director: Carolyn Gleason

Creative Director: Jody Billert

Managing Editor: Christina Wiginton

Editor: Laura Harger

Editorial Assistant: Jaime Schwender

Edited by Gregory McNamee

eBook design adapted from printed book design by Jody Billert

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Chittum, Samme, author.

Title: Last days of the Concorde : the crash of Flight 4590 and the end of supersonic passenger travel / Samme Chittum.

Other titles: Smithsonian air disasters series.

Description: Washington, DC : Smithsonian Books, [2018] | Series: Smithsonian air disasters series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018011673 | ISBN 9781588346292 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Aircraft accidentsInvestigation. | Concorde (Jet transports)Accidents. | Concorde (Jet transports)History.

Classification: LCC TL553.5 .C486 2018 | DDC 363.12/40944367dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018011673

Ebook ISBN9781588346315

v5.3.2

a

Contents

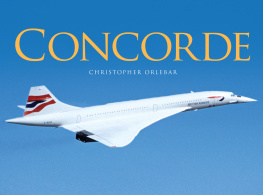

The White Bird

Through its small oval windowsno larger than an outspread human handa Concorde jet plane zooming through the stratosphere at supersonic speed offered its passengers a view like no other. The limitless darkness of space seemed almost near enough to touch, while below the distant earth revealed its subtle curve, best appreciated from the passengers lofty height of 17.7 kilometers (11 mi) above sea level. Travelers were temporary superheroes, flying faster than a speeding bullet, and with a celebratory flute of fine champagne in hand. The futuristic lines of the slender white plane emphasized the rarefied nature of travel within it.

Concorde was a time machine. By reducing intercontinental flight times by almost half, it effectively turned back the clock, making it possible for passengers to leave Paris at 10:30 a.m. and step off the plane in New York at 8:15 a.m. Concorde itself seemed always a step ahead of the present, a hypermodern dream machine whose sleek delta wing, ultrathin fuselage, and characteristic needle nose made it both odd and arresting. Above all, flying Concorde was an experience, one that conferred a feeling of exclusivity and a sense of adventure. Passengers enjoyed the sense of a guaranteed happy ending to such flights, too, for during its 31-year history, not a single Concorde had been involved in a fatal accident.

Tuesday, July 25, 2000, was a weekday much like any other at the one of the busiest international airports in Europe, where air traffic controller Gilles Logelin was working the second shift in the southern control tower at the Aroport ParisCharles de Gaulle. Early-morning storm activity had delayed flights in France and elsewhere in Europe, creating a backlog of planes waiting to take off and land. Frustrated travelers stood in long lines, only to be told they could not make their connecting flights at other airports. By early afternoon, however, although the air remained muggy, the skies had cleared, making life and working conditions pleasant for controllers stationed near the top of the 22-story tower. It was a perfect summer daya typical summer day that you have in the Paris area, and a good day for flying, recalls Logelin. Only a few clouds remained in the otherwise blank blue sky. Summer is holiday and tourist season in France, and July and August are the busiest months of the year at Charles de Gaulle, informally known as the Roissy Airport for the district that surrounds it. Logelin remembers that Tuesday as a normal day, despite an adjustment to his schedule that at the time seemed trivial. One of my colleagues had asked to exchange his shift with mine, so I was on duty on this particular afternoon instead of being on duty in the morning.

Four other controllers were stationed in the tower. Logelin was the acting local controller, whose job it was to observe the planes using the two parallel runways that run east to west across the southern sector of the airport near Terminal 2no small feat, given the 1,500-plus aircraft that landed and took off from Charles de Gaulle every 24 hours. Planes of all sizes, both commercial and private, came and went seven days a week from the gateway airport, which sits 25 kilometers (16 mi) northeast of the capital. Learjets and Cessnas carrying corporate executives to other cities in France made use of the same runways as larger commercial airplanes, including long-range jetliners such as the Boeing 747 and McDonnell Douglas DC-10, and the short/medium-range planes like the Airbus A320 and McDonnell Douglas MD-80.

Thus Logelins normal Tuesday included the usual bustling mass of air traffic, which he monitored both on his radar screen and through the windows of the ultramodern control tower. His perch in the observation post of the concrete and aluminum tower, completed in 1999, was designed for maximum exterior visibility and granted him a unique eagles-eye view of the two runways to the south. The faade of the towers supporting column was made primarily of tinted glass; at the very top, the oval observation post where Logelin and the other controllers worked was surrounded by specially made floor-to-ceiling nonreflective windows.

Charles de Gaulle Airport in some ways resembles a small city that must manage and maintain 71 kilometers (44 mi) of taxiways connecting its four runways and three terminals, along with the welter of restaurants, hotels, car rental offices, parking lots, currency exchange counters, and endless outbuildings characteristic of any great airport. In the year 2000 alone, the airport was the pass-through point for 48 million passengers. As befits a country famed for aesthetics, the airport is renowned for its design; it even commissioned its own sleek sans-serif typeface, once called Roissy and now known as Frutiger, to grace its internal signage. Its distinctive 10-story Terminal 1, which opened in 1976 and was designed by international starchitect Paul Andreu, is often compared to an octopus because of its modernist circular structure and the iconic white connector tubes that shuttle passengers among its seven satellite gates. Terminals 2 and 3 were added in the 1980s and 1990s to allow the airport to expand. Terminal 2, a series of seven connected buildings, sits south and east of Terminal 1 and is known for the gigantic wood-and-glass-framed hall known as Terminal 2E. The airport has a pair of control towers; the southern one, Logelins base, sits near Terminal 2.