Contents

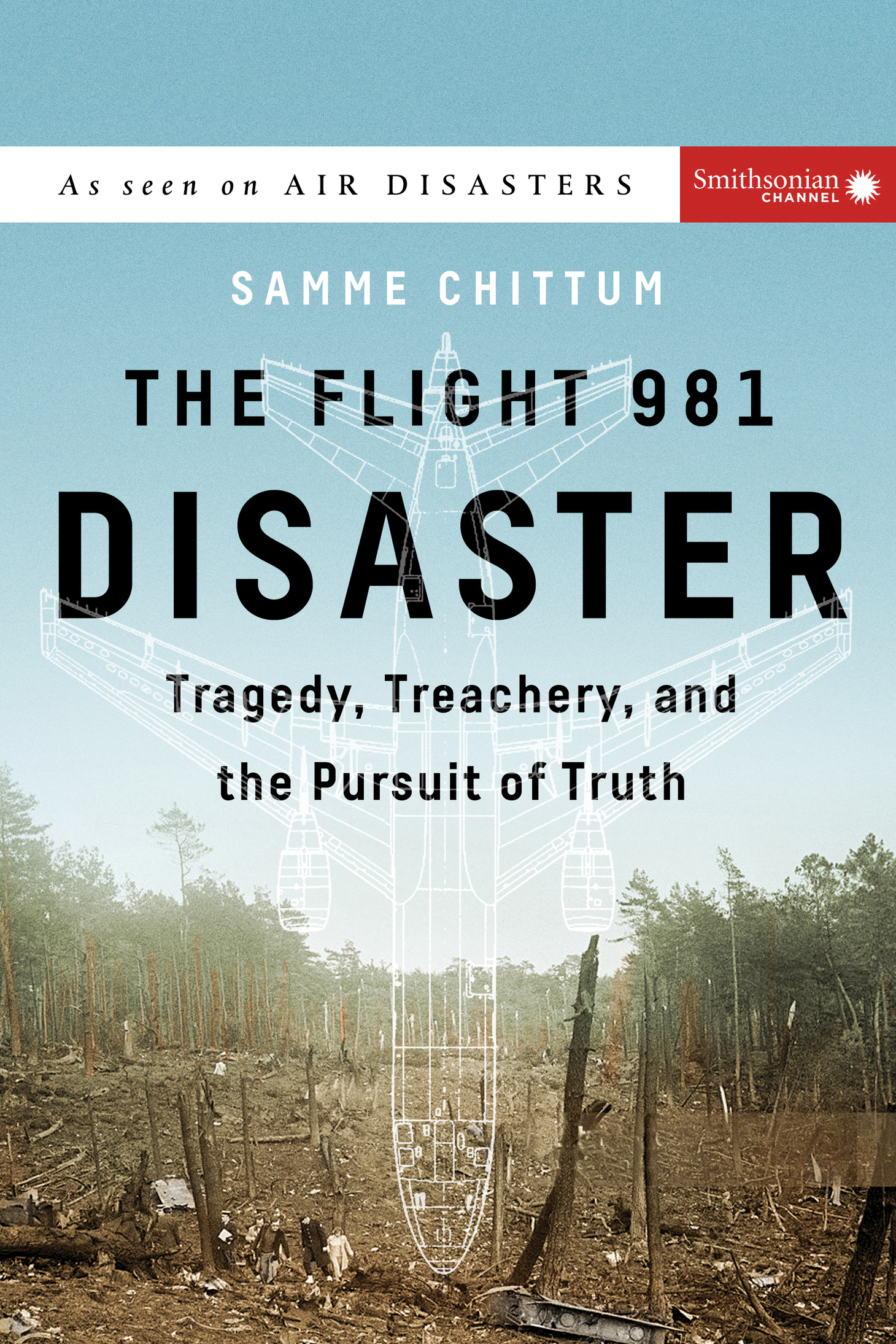

Smithsonian Air Disasters Series

Suspenseful stories of tragedy and triumph are brought to life in the Smithsonian Air Disasters television and book series through investigative reporting, official reports, and interviews with the pilots, air traffic controllers, and survivors of historys most terrifying crashes. From the cockpit to the cabin, from the control room to the crash scene, the Air Disasters series uncovers what went wrong and reveals the changes that were made to ensure such disasters never happen again.

Upcoming titles include:

Southern Storm: The Tragedy of Flight 242

Explosive Evidence: The Air India Flight 182 Disaster

2017 by Cineflix Media Inc. and Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Based on Air Disasters: Behind Closed Doors, created by Cineflix and shown in the United States on the Smithsonian Channel.

Published by Smithsonian Books

Director: Carolyn Gleason

Managing Editor: Christina Wiginton

Project Editor: Laura Harger

Editorial Assistant: Jaime Schwender

Edited by Emily Park

eBook design adapted from printed book design by Jody Billert

Indexed by Scribe Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Chittum, Samme, author.

Title: The Flight 981 disaster : tragedy, treachery, and the pursuit of truth / Samme Chittum.

Description: Washington, DC : Smithsonian Books, [2017] | Series: Air disasters | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017001139 | ISBN 9781588346032

Subjects: LCSH: Aircraft accidentsFranceSenlis RegionInvestigation. | McDonnell Douglas DC-10 (Jet transport). | AirplanesCrashworthiness.

Classification: LCC TL553.53.F8 C45 2017 | DDC 363.12/4650944264dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017001139

Ebook ISBN9781588346049

v4.1

a

Blowout in Midair

T he tropopause is not a moment but a placea blue boundary between above and below, an intermediate zone in the earths atmosphere. Below it is the troposphere, where weather rules and humans live and breathe. Above it is the higher, ethereal stratosphere, the second major atmospheric layer above the earth, where jets cruise like celestial ocean liners. The height or ceiling of the troposphere and the bottom of the stratosphere vary with seasons and latitudes, ranging from 3.7 miles, or 20,000 feet, to 12 miles, or 65,000 feet.

For pilots, the tropopause is a perimeter to be crossed in order to escape wind, rain, and lightning. But for most of us, crossing this boundary is an experience made noteworthy by the moment on a flight when we realize that we have ceased to look up at clouds and instead are looking down on them. This view is circumscribed by the essential geometry of an airplanes design, the framing oval window and the bisecting, slanted edge of a wing. But it retains its power to invoke our inner poet: the one who ponders the fragility of life and the mysterious physics of flight that enable a 215-ton aircraft to fly at altitudes higher than the peak of Mount Everest; the one who wonders how we would feel or behave if something were to go wrong, if one of the thousands of vital parts that make up an airplane were to cease to perform in harmony with all the other parts, and to do what machines sometimes do, which is to break, give way, and fail.

On June 12, 1972, American Airlines Flight 96 should have come very close to the tropopause at its assigned flight level of 21,000 feet, but it never made it that far. As a practical matter, aircraft seldom experience problems in midair. The vast majority of accidents occur during takeoff or landing, when pilots put themselves and their planes through their paces. The stratosphere is where jet engines function most efficiently, where autopilot systems are switched on and the crew in the cockpit can collectively relax. Thus, all seemed well at 11,750 feet when Flight 96, a DC-10-10, broke through a spotty cloud layer over the Canadian industrial city of Windsor, Ontario. Just five minutes had passed since the wide-body jet had lifted off the runway at Michigans Detroit Metropolitan Airport at 7:20 p.m. Captain Bryce McCormick took a moment to appreciate the 180-degree view through the expansive, curved window of the cockpit. The gray spires of half a dozen high-rise buildings and an unremarkable cluster of office buildings defined downtown Windsor, which lies on the southern bank of the wide and winding Detroit River. In the fading spring light, McCormick could still see motorboats plying the silvery surface of the choppy river. He had flown southeast out of Detroit many times before, but he never tired of the panoramic view of this corner of the magnificent Great Lakes system. The Detroit River is a natural boundary between the United States and Canada and a visual marker for pilots. And it links Lake Saint Clair, to the north, with Lake Erie, to the east, where the plane was headed. The immense and brooding lake, famous for its squalls, got its name from the Iroquoian word erie, for cat, because it is unpredictable.

The weather was unseasonably wet and mild for June, but the temperature inside the cockpit was neither too cool nor too warm. McCormick leaned back and took a sip of coffee from a cup cradled in the black vinyl console next to his seat. Flight 96 was on its way to LaGuardia Airport in New York City, with a stopover in Buffalo, New York. McCormick had flown the first leg of the flight, out of Los Angeles, that morning, so he let First Officer Peter Paige Whitney, 34, fly the takeoff from Detroit. All the gauges on the instrument panel registered as normal. And the planes three turbo-fan Pratt & Whitney engines, two under the wings and one mounted on the tail, were performing beautifully. The autopilot was on, but Whitney kept his hands on the yoke out of habit.

McCormick glanced upward and spied a Boeing 747 in the skies far above them. The regal jumbo jet was climbing toward its eventual 30,000-foot cruising altitude in the lower stratosphere. Smaller jets, such as their DC-10-10, were built to cruise as high as 42,000 feet above sea level, but it did not need to go that high during shorter flights, such as this one from Detroit to Buffalo. Whatever the altitude, the planes internal environment was completely contained and regulated. If the passengers closed their eyes, they could easily imagine they were sitting in their own living rooms. McCormick turned to Whitney, pointed at the Boeing 747, and said, There goes a big one up there. His first officer leaned forward to get a better look at the jumbo jet and its impressive 200-foot wingspan.