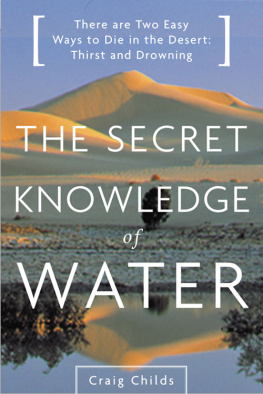

Copyright 2000 by Craig Childs

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Originally published in hardcover by Sasquatch Books, March 2000

Hachette Book Group, 237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

The Sasquatch Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: May 2001

ISBN: 978-0-316-05530-7

Book design by Kate Basart

Craig Childs

contributes regularly to National Public Radio's Morning Edition. He camps in the wilds of the American West several months of the year, usually living in the back of his truck, out of a river vessel, or from his backpack. His other books include Crossing Paths: Uncommon Encounters with Animals in the Wild.

The Secret Knowledge of Water

A Top Ten Book Sense Pick

Selected by the Los Angeles Times as one of the best nonfiction books of the year

Selected as a Southwest Book of the Year

The scenes Childs takes us to and the facts he recounts are utterly memorable and fantastic. This is a direct book in which the author is on fire with his subject and grabs whatever lies at hand that might help him testify. It's an approach that is without affectation, and that puts the reader right there with him dropping down that waterfall into what turned out to be a waist-deep pool. The net result is that one comes out of the book feeling that the experiences recounted in it are one's own. Certainly no reader will ever see the desert in the same way again.

Suzannah Lessard, Washington Post

An astute observer of nature and a concise writer with a knack for storytelling, Childs meticulously records each significant occurrence in an attempt to understand how the absence or presence of something most of us take for granted dictates life and death in the harsh environment. Highlights include terrifying accounts of flash floods and a fascinating cave exploration, complete with wet suits, deep in the Grand Canyon.

Tim J. Markus, Library Journal

The Secret Knowledge of Water exhibits an almost spiritual feel for the desert and its inhabitants. Childs's knack for storytelling, his broad knowledge of the desert environment, and his conversations with a diverse group of geologists, ecologists, conservationists, and archaeologists bring added insight to his narrative.

Cait Goldberg, Science News

Sometimes a book comes along that is pure oxygen. Be forewarned: Like all truly oxygenated items, The Secret Knowledge of Water is an extremely erotic book. Childs rubs desert lavender between his hands. He hears voices in his ears; he clutches sandstone and the walls of caves; best of all, he describes sounds: 'the liquid timbre in thin canyons, water running where there is no sound elsewhere, no water even if I walked for days. Vowels lifted from purl. Whole words.'

Susan Salter Reynolds, Los Angeles Times Book Review

Sprinkled throughout the book are fifteen line drawings by Regan Choi that are usually delightful, like shining gems in the desolate sand. Also sprinkled throughout the book are wonderful uses of the English language. The Secret Knowledge of Water certainly deserves to be considered in the same company as Edward Abbey's Desert Solitaire and Marc Reisner's Cadillac Desert.

Martin Napersteck, Salt Lake Tribune

Stone Desert: A Naturalist's Exploration of Canyonlands National Park

Crossing Paths: Uncommon Encounters with Animals in the Wild

Grand Canyon: Time Below the Rim photographs by Gary Ladd

Grand Canyon Stories: Then and Now with Leo W. Banks

Colorado

photographs by Art Wolfe, with Gavriel Jecan

In memory of Josh Ruder,

who was taken by the water

Without the inspiration, hard work, and friendship of Walt Anderson, few of these words would have come to paper. I have been humbled by his knowledge and propelled by his enthusiasm.

I am also indebted to my editor, Gary Luke, for asking gentle, necessary questions, drawing this story into the light. There have been many other people who have made this work possible, countless researchers who have added to the body of knowledge from which I have drawn. Among them, I especially thank Ellen Wohl, Bob Webb, Dennis Kubly, Father Charles Polzer, W. L. Minckley, Gale Monson, and Gayle Hartmann. I also thank the Nature Conservancy's Muleshoe Ranch and Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge for allowing me to perform research on their lands. Finally, thank you to my father, who was born in the desert and, during the floods and storms recorded in this book, died in the desert. Thank you for making certain that my eyes were always wide open.

First Waters

MY MOTHER WAS BORN BESIDE A SPRING IN THE HIGH desert, just north of where West Texas and Mexico meet along the Rio Grande. Born three months premature, she was kept alive in an incubator heated with household lightbulbs. An eyedropper was used for feeding. The water from the spring bathed and filled her body, tightening each of her cells. It filled the hollow of her bones. Years later, as the water passed from mother to child like fine hair or blue eyes, I grew up thinking that water and the desert were the same.

Beyond the spring grew pion and juniper trees, their wood grossly twisted from years of drought, while here, where my mother was born, cress and moss grew from the spring. A weeping willow, imported from an unfamiliar place, dusted the surface with seeds. I traveled there once, walking up and pushing away the downy willow seeds with the edge of my hand. I dipped two film canisters below the surface. I capped these, walked back to my truck, and drove away before a Introduction stranger could appear from the nearby house to run me off the property.

I figured that the water might come in handy someday. If my mother ever grew ill and her death was near, I would bring this water to her. The spring had kept many people alive before her. It was an essential stopover for Spanish explorers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and for whomever traveled the desert for the previous millennia. I would slip its water between her lips, tilting her head up with my palm. Her body might recognize it, the way salmon make sudden turns to follow obscure creeks, the way dragonflies work back to the one water hole held between desert mesas.

An early memory of the low Sonoran Desert where I was born is of my mother walking me out on a trail. I remember three things, each a snapshot without motion or sound. The first is lush, green cottonwood trees billowing like clouds against the stark backdrop of cliffs and boulders. The second is tadpoles worrying the mud in a water hole just about dry. Each tadpole, like the eye of a raven, waited black and moist against the sun. The third is water streaming over carved rock into a pool clear as window glass. These three images are what defined the desert for me. At an early age it was obvious to me that water was the element of consequence, the root of everything out here. Even to say the word Sonoran required my lips to form as if I were about to take a drink, and the tone of the word hovered in the air the same as agua or water.

The desert surface is carved into canyons, arroyos, caoncitos, ravines, narrows, washes, and chasms. The anatomy of this place has no other profession but the moving of water. When you walk out here, you walk the places where water has gonethe canyons, the low places, and the pour-offsbecause travel is too difficult against the grain of gullies or up in the rough rock outcrops.