History for a Sustainable Future

Michael Egan, series editor; Peter S. Alagona, Benjamin R. Cohen, and Adam M. Sowards, associate editors

Derek Wall, The Commons in History: Culture, Conflict, and Ecology

Frank Uektter, The Greenest Nation? A New History of German Environmentalism

Brett Bennett, Plantations and Protected Areas: A Global History of Forest Management

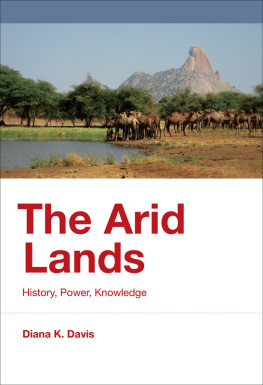

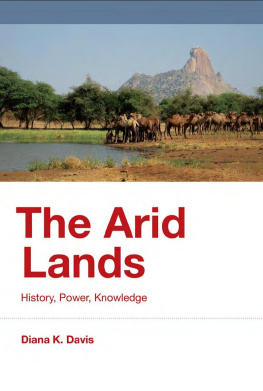

Diana K. Davis, The Arid Lands: History, Power, Knowledge

The Arid Lands

History, Power, Knowledge

Diana K. Davis

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2016 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in Sabon by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited. Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Davis, Diana K.

Title: The arid lands : history, power, knowledge / Diana K. Davis.

Description: Cambridge, MA : The MIT Press, [2015] | Series: History for a sustainable future | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015039696 | ISBN 9780262034524 (hardcover : alk. paper)

eISBN 9780262333528

Subjects: LCSH: Deserts. | DesertsHistory. | Arid regions. | Desert ecology. | Desert resources development.

Classification: LCC QH88 .D384 2015 | DDC 577.54dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015039696

10987654321

I dedicate this book to JEH, MBDH, and CADH. Always and forever. Also to my parents, Jan and David Davis, and to the memory of David Hooson, wise mentor and friend.

Very little rain falls in the land of Assyria [Iraq]. Of all the lands that we know, this is far the most fertile for Demeters crop [grains].

Herodotus, c. 440 BCE

Present wastelands and sandy deserts were fertile lands in former ages [and] the condition might be reversed.

George Hakewill, 1627

A single forest [planted in Arabia] in the middle of these burning deserts would be adequate to temper them, by leading rain to them.

Buffon, 1778

Before him lay original nature in her wild and sublime beauty. Behind him he leaves a desert, a deformed and ruined land.

Schleiden, 1848

Desertification is purely artificial. It [is] caused uniquely by human action.

Lavauden, 1927

The United Nations could be considered to have created desertification, the institutional myth.

Thomas and Middleton, 1994

Let deserts be.

El-Baz, 2008

Ergs are like waves in the desert and the desert is like the beach without the sea.

Max and Corbin, 2015

Foreword

Michael Egan

We creatures of reason, we dont live fully; we live in an arid land, even though we often seem to guide and rule you.

Herman Hesse, Narcissus and Goldmund: A Novel

Did you have a good Pleistocene? The Australian polymath George Seddon asked this question as part of his geological history of Australia.

It has long seemed to me that when the continents are being handed out, the question one should press hard is Did you have a good Pleistocene?, because glaciers and continental ice-sheets are among the great soil-makers, grinding up fresh rock full of nutrients most plants need. The Pleistocene gave America the Great Plains, China its fertile loess, and much of central Europe its good soils. Glaciers, with their deep V-shaped valleys, also provide good dam sites and, when they meet the sea, deep harbours.

In some sense, Diana Daviss book examines the relatively recent history of the regions of the world that had a bad Pleistocene: those places where good earth and ample waters have always been scarce. But her history of deserts, desertification, and arid lands is no deterministic account of deserts on the march or landscapes on the brink. Rather than compare and bemoan a series of satellite images of receding lakes and seas the world over, The Arid Lands: History, Power, Knowledge offers a much more nuanced interpretation. Inasmuch as deserts are a natural feature of our planets ecosphere, humans are responsible for the modern idea of desertification. The simple assumption would be to point to anthropogenic climate change, but Davis advocates the importance of place and of reconceiving colonial narratives.

Davis, who has lived and worked in the arid lands most of her life, wishes to complicate our common understanding of deserts as wastelands. Just as we do not have a universal quantification for arid, desertification has no agreed-upon definition. Dry and more dry are relative terms. But we can take this a step further and acknowledge that this language is loaded. In her recent work on the history of wastelands, Vittoria Di Palma reflects on the synchronous and intertwined etymologies of desert, wilderness, and wasteland. In the biblical texts, she writes, wilderness tends to signify a land that is and has always been barren. In contrast, wasteland is more often used in contexts where a place is barren and desolate as the result of an act of destruction.

Western/northern environmental ideals have shaped much of our contemporary explanations for and understanding of desertification. The ghost of Thomas Malthus looms large: famines are blamed on untenable carrying capacities: overgrazing and overpopulation, which lead to catastrophe. They are the fault of indigenous peoples not adopting modern, scientific practices, relying instead on nomadic lifestyles. Davis shows that, ironically, it was the imposition of colonial powers and export economies stressing arid lands to the breaking point that were ultimately responsible for distress. Discouraging nomadic pastoral activities, redirecting water to foster more sedentary livelihoods, and misdirecting blame for arid lands have been the bedrock of modern approaches and failures. In short, deserts do not work the same way that temperate landscapes do. This is in no way a defense of capitalist extractive practices in some regions and not in others, but rather a castigation of a one-size-fits-all interpretation of land management as conceived by colonial managers and inherited during the postcolonial period by world powers and their financial institutions. And given their land mass, we would do well to better heed the rhythms and flows of deserts. It is no accident that the majority of desert pastoralists do not stay put. Out of necessity, they remain mobile.

In Zagora, at the northern edge of the Sahara Desert in Morocco, there is a famous sign that points to Timbuktu, directly south across the desert in Mali. Rather than offering the distance in kilometers, the signfor camel trainsmarks 52 jours. According to Google Maps, the route hasnt become much easier. Its recommended passage involves a circuitous route along the coast that totals 4,695 kilometers. The 52 days seems almost easier. The underlying message remains constant: this is the edge of civilization, the border of desolation. Beyond here lies nothing.

But there are two stories that arid lands evoke. The presentist narrativebuoyed by drought and famine crises over the past half-centuryalerts us to the notion of a world on the verge of collapse. Desert creep, the expansion of arid lands, is a part of much larger global processes. Global warming has forced more and more people into migration. These climate refugees are being chased from landscapes from which they can no longer scratch out subsistence. They are the poorest of the poor, the story goes, exiled to fringe landscapes that can no longer sustain them. The consequences of these global changes have the most devastating impacts on the poorest, who historically have had limited entitlements and opportunities for growth. Deserts and their expansion constitute an important canary in the proverbial coal mine. They are sensitive landscapes, impoverished by bad Pleistocenes and scientific efforts to rehabilitate them or render them more efficient. The presentist narrative warns that these sensitive landscapes have reached their tipping point, and that the global implications of this will reach well beyond dunes and poor soils. Desertification is an omen of a bleak future.