DESERTS AND STEPPES

THE LIVING EARTH

DESERTS AND STEPPES

EDITED BY JOHN P. RAFFERTY, ASSOCIATE EDITOR, EARTH AND LIFE SCIENCES

Published in 2011 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.)

in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2011 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2011 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

John P. Rafferty: Associate Editor, Earth and Life Sciences

Rosen Educational Services

Alexandra Hanson-Harding: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Matthew Cauli: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Catherine Vanderhoof

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Deserts and steppes / edited by John P. Rafferty1st ed.

p. cm. -- (Living earth)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-391-5 (eBook)

1. Deserts. 2. Desert ecology. 3. Steppes. 4. Steppe ecology. I. Rafferty, John P.

GB611.D475 2011

551.41'5dc22

2010022143

On the cover: Sidewinder snakes, like the one pictured here, live in deserts of the U.S. Southwest and northern Mexico. They prey on lizards and small mammals. Paul Chesley/Stone/Getty Images

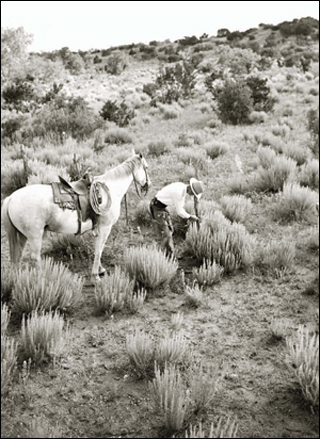

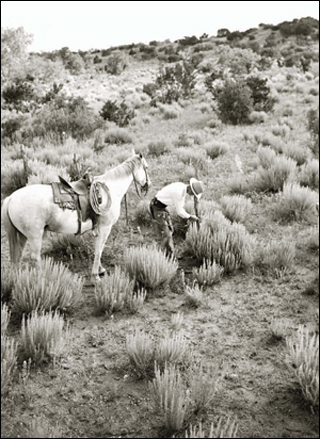

Page : A cowboy repairs a fence in the avid U.S. Southwest. Hansel Mieth/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

On pages : Sand is rippled by the wind at the Imperial Dunes, part of the Colorado Desert, near Winterhaven, California. David McNew/Getty Images

INTRODUCTION

F or many people, the thought of the desert conjures up images of vast expanses of sand, shifting dunes, sparse vegetation, and little water. Such a landscape is one type of desert, but it is neither the only nor the most typical one. The Gobi desert in China and Mongolia, for example, is not a sandy desert. It is made up of nearly 1,300,000 square km (500,000 square miles) of mostly bare, flat rock. In contrast, the desert landscape found in the Great Basin in Nevada and Utah is largely made up of a series of mountain ranges and closed valleys, and the American Southwest is rich with distinctive saguaro cactus. In this book you will explore the unique deserts of the world, along with the different semiarid environments that often surround them.

Deserts are one of Earths major biomes, covering 20-30 percent of Earths land area, depending on which definition is used. They are surprisingly diverse in their landforms, vegetation, and animal life. Unlike temperate forests, which appear as wide swaths of continuous growth, each desert is an isolated environment. In other words, no two deserts share the exact same flora and fauna, although they may support similar species with similar adaptations to the harsh desert environment.

One characteristic that all deserts have in common is an extreme lack of rainfall. Some parts of deserts may go years without any rain at all. More typically, deserts experience long months of little or no precipitation, interspersed with short, heavy rains that fall on a few days a year. Desert rainfall generally amounts to less than 400 mm (16 inches) of annually. Some classification systems limit true deserts to those areas receiving less than 250 mm (10 inches) of water per year.

The lack of rainfall also leads to another characteristic common to all deserts, which is the sparseness of vegetation. Trees are generally absent, and much of the ground has no plant cover at all. The plants that do exist have adapted in a variety of ways to the lack of available moisture. Succulents, such as cacti, take in water when its available and store it in their tissues. During moist conditions, plants that produce seeds, which remain dormant until water is available, suddenly blossom and set seed again within days. Some plants in coastal desert regions even absorb water from fog and dew directly through their leaves.

The sparse vegetation of desert regions limits the number of animals that the desert environment can support. Most deserts have few large herbivorous species, although one group, the camels, are famously adapted to desert life. In Africa and Arabia, most camels are in domesticated herds. Wild camels, however, can be found in Asia and also in the Australian Outback, where they were introduced in the 1800s. Smaller mammals, such as porcupines, hares, and jerboas, are common in many deserts, and some deserts also support a wide variety of lizards and other reptiles. Kangaroos and related marsupials such as wallabies and bandicoots range through the Australian Outback. Desert carnivores include hyenas, foxes, and a variety of large cats, as well as many species of carnivorous birds such as vultures.

Deserts are not generally conducive to human habitation. The Sahara desert, the largest in the world, is approximately the same size as the United States, but supports only about 2.5 million inhabitants. The deserts human residents are clustered in small settlements wherever reliable water sources allow for farming or the grazing of animals. The Gobi also supports a population of mostly nomadic livestock herders that occur in densities of about 1.3 persons per square km (about 1.1 persons per square mile). The Namib desert in southwestern Africa contains large areas set aside as conservation preserves, but it is almost completely uninhabited except along the coast. In the Arabian peninsula, the discovery of vast oil reserves under the desert have allowed significant development in that region, and many of the traditional Bedouin, a nomadic people, have settled into permanent habitations.

In many cases, intensive agriculture and the stresses of human settlement in or near desert regions have caused the spread of desert conditions into bordering semiarid grazing or agricultural areas. Such desertification is typically caused by the overuse of the land and its resources. Specifically, desertification may result from deforestation, overgrazing, unsustainable irrigation practices, or combinations of these factors. Desertification is of particular concern in the Sahel region of Africa just to the south of the Sahara, as well as areas adjacent to the Kalahari desert of southern Africa. It occurs in parts of Australia, in Central Asia near the Gobi and Takla Makan deserts, and even in parts of North America. The United Nations has declared desertification, along with its associated effects on human populations, to be one of the most severe environmental challenges the planet faces.

Next page