To find a common future together, we must reconstruct our common past.

Manning Marable,

The Great Wells of

Democracy

P eople said that Mrs. Newton kept Negroes in her attic, that her abandoned house was haunted. Those were rumors circulating in Highland Park in the mid-1950s, in the days before it became such an exclusively wealthy white township of comfortable homes inside the city of Dallas. I was about ten when I first heard whispers of Cosette Faust Newtons story. My return as an adult, to research her story for an article, set me off on a path that eventually led me to the story of Love Cemetery, a small, rural, African American burial ground in East Texas.

Cosette named her house the Miramar, after her street, a few blocks from my grandparents home in Highland Park. The front yard of the Miramar was surrounded by a barbed-wire-topped chain-link fence. Heavy jail-bar doors and barred windows hung throughout the house, inside and out, and were clearly visible from the street. The rest of the block was filled with large, well-landscaped homes.1 Instead of a neatly trimmed lawn like her neighbors, Cosette had scattered thirteen open red-and-white metal umbrellas, anchored in concrete blocks, around the front yard. As a finishing touch, she had hand-lettered a sign stuck in the front yard that read: For Sale to Negroes Only.

When I was sixteen, I finally worked up the nerve to try to sneak in and up to the third-floor attic, where she supposedly kept Negroes imprisoned, to see if there were still any chains there. Just as my girlfriend, my accomplice of the moment, and I started up the third-floor stairs, we heard footsteps. We froze, convinced that the house was really haunted. But when we turned around, we saw two uniformed Highland Park police officers. We were arrested and taken down to the station and booked on charges of trespassing. My mother came and bailed us out. Cosette pressed charges. We made our court appearance and escaped punishment by swearing that we would never again go in the Miramar.

I kept the promise Id made to the judge that late summer day in Dallas and forgot about the Miramar until I was an adult, a writer living across the country. Then, one night, a poem I was reading, called Abandoned Places, brought that house back to methat battered, abandoned, bizarre place out of my childhood.2 I went back to investigate, discovered the other side of the story, and wrote about it.3

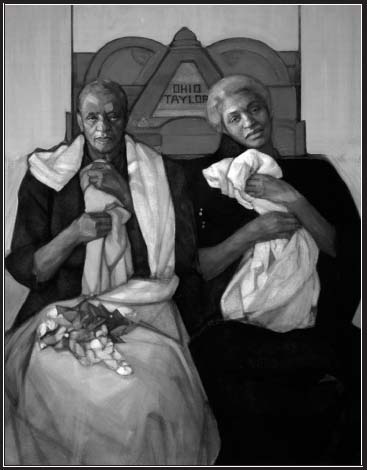

It wasnt a ghost story; Cosette, a Ph.D., M.D., and a former Dean of Women at Southern Methodist University with half a dozen more degrees, had kept a prisoner in her attic. In a front-page story in the Dallas Morning News of July 30, 1938, was a photograph of Cosette and her African American gardener, Mickey Ricketts, just after he had been rescued by the police. Mickeys face was wrapped in medical bandages with only a large opening for his mouth. He had been captive in her attic; no one was quite sure for how long, less than a week it seemed. I tracked down Chief Gardner, the retired police officer who had arrested her for kidnapping. Chief Gardner had carried the weakened Ricketts down three flights of stairs. When I asked the officer why Cosette would have kidnapped Mickey, he assured me that Mrs. Newton was just crazy.

Then I went looking for Mickey Ricketts. I wanted to hear his side of the story. He could have still been alive when I started my research in the 1970s, so I plunged into the black community to find him. As I started to ask questions, I heard a different narrative than the one reported by the officer or the press. I found the sister of William Earl Harrison, Cosettes chauffeur, one of the African American men Cosette employed to help kidnap Mickey. Harrisons sister told me that Cosette knew exactly what she was doing; she wasnt crazy. She wanted him for sex.

I had entered another side of the story.

A different African American woman with whom I spoke claimed that Dr. Frank Newton, Cosettes husband, knew about and tolerated Cosettes sexual use of Mickey. Dr. Frank never said no to Cosette. She told me that Cosette bathed Mickey, perfumed him, dressed him in satin pajamas, and that Mickey was utterly terrified of her. Mickey ran away from Cosette. He wanted out. Thats why she had him kidnapped.

Cosette claimed that Mickey had stolen a valuable jade ring from her and that what went on in the attic was simply an interrogation, with the help of a former FBI agent, to get the truth out of Mickey. In the end, the charges against Cosette were reduced to a misdemeanor. Mickey Ricketts settled out of court for $500 and left town.

But there was another crime here, a murder. According to Harrisons sister and others in the African American community, William Earl, Cosettes chauffer, had stepped forward to testify on Rickettss behalf and got shot for it by one of her lawyers. In fact, there were newspaper accounts that one of Cosettes attorneys had killed a Negro man who entered the office. The attorney claimed self-defense and was never charged for Harrisons murder, even though Harrisons death certificate listed homicide as the cause. Harrison, unarmed, had been shot three times in the neck and head, in the attorneys office. Harrisons family sued for damages. But it was the white attorneys word against a dead black mans in Texas in the 1930s. The suit went nowhere.

I kept looking. I found out that there was a black newspaper published in Dallas in the 1930s. Founded in 1892, the Dallas Express had a different perspective on Cosettes story than the Dallas Morning News , the mainstream white paper. It echoed the points of view I had heard in the black community, while the News painted Cosette as merely eccentric and intimated that Mickey must have done something wrong to have gotten himself into such a position. The Dallas Express gave credence to the idea that there was more to the story and that Harrison, who was about to talk, had been murdered to keep him quiet.

Though I found no proof of the nature of Cosettes relationship with her gardener, I did find the court records, the newspaper storieslargely from the white perspectiveand William Earl Harrisons death certificate.

Over the years, as I continued the lines of research that Cosettes story had started me on, I discovered a history full of lynchings, of Ku Klux Klan and Citizens Council violence, of black disenfranchisement, and I understood that this history was part of a larger narrative that continues to unfold today, like a troubling, transparent overlay on the map of the United States, especially the map of TexasEast Texas, where my great-grand-parents on my mothers side settled in 1900 and where the story of Love Cemetery begins.