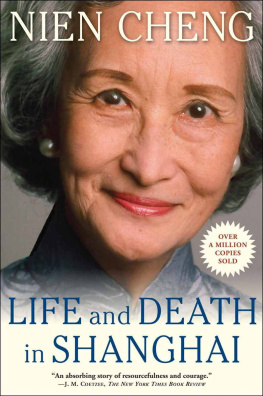

Cheng - Life and Death in Shanghai

Here you can read online Cheng - Life and Death in Shanghai full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: China, year: 2010;1986, publisher: Grove Atlantic;Grove Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

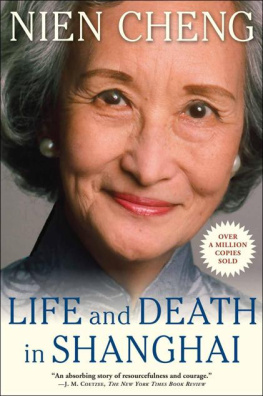

- Book:Life and Death in Shanghai

- Author:

- Publisher:Grove Atlantic;Grove Press

- Genre:

- Year:2010;1986

- City:China

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life and Death in Shanghai: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Life and Death in Shanghai" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Cheng: author's other books

Who wrote Life and Death in Shanghai? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Life and Death in Shanghai — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Life and Death in Shanghai" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Praise for Life and Death in Shanghai:

Far from depressing, it is almost exhilarating to witness her mind do battle. Even in English, the keenness of her thought and expression is such that it constitutes some form of martial art, enabling her time and again to absorb the force of her interrogators logic and turn it to her own advantage.

Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, The New York Times

A triumph of the human spirit Here is the most stunning human document out of China since the Cultural Revolutionperhaps since the Revolution itself.

Clifton Fadiman

A harrowing story of personal suffering and tragedy, and at the same time a savage and compelling indictment of Mao Zedongs Cultural Revolution, if not of Chinese communism itself an extraordinary testament to human brutality.

Elena Brunet, Los Angeles Times

Her book is unquestionably one of the best ever written about the Cultural Revolution.

Houston Chronicle

An almost unbearably vivid picture of personal suffering and triumph.

Chicago Tribune

Nien Cheng

Copyright 1986 by Nein Cheng

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or permissions@groveatlantic.com.

Printed in the United States of America

E-Book ISBN: 978-0-8021-9615-6

Designed by Irving Perkins Associates

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

To Meiping

THIS BOOK is a factual account of what happened to me during the Cultural Revolution. The events are recorded in chronological order, just as they occurred. Every word spoken at the time, the reader will soon understand, was vitally important. Indeed, my survival depended on what was said to and by me. I had ample time again and again to recall scenes and conversations in a continuing effort to assess their significance. As a consequence, they are indelibly etched on my memory, and my book, including the words quoted as direct discourse, is as nearly as possible a faithful account of my experiences.

With some reluctance, I use in this book the now standard pinyin system for the transliteration of most of the Chinese names. Among the few exceptions are such old, familiar forms as Hong Kong (pinyin: Xianggang) and Kuomintang (Guomin-dang), and my husbands, my daughters, and my own name (Zheng), which I prefer to continue to spell in English as I have done for more than fifty years.

I

THE WIND OF REVOLUTION

II

THE DETENTION HOUSE

III

MY STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE

THE WIND OF REVOLUTION

Witch-hunt

THE PAST IS FOREVER with me and I remember it all. I now move back in time and space to a hot summers night in July 1966, to the study of my old home in Shanghai. My daughter was asleep in her bedroom, the servants had gone to their quarters, and I was alone in my study. I hear again the slow whirling of the ceiling fan overhead; I see the white carnations drooping in the heat in the white Qianlong vase on my desk. Bookshelves line the walls in front of me, filled with English and Chinese titles. The shaded reading lamp leaves half the room in shadows, but the silk brocade of the red cushions on the white sofa gleams vividly.

An English friend, a frequent visitor to my home in Shanghai, once called it an oasis of comfort and elegance in the midst of the citys drabness. Indeed, my house was not a mansion, and by Western standards, it was modest. But I had spent time and thought to make it a home and a haven for my daughter and myself so that we could continue to enjoy good taste while the rest of the city was being taken over by proletarian realism.

Not many private people in Shanghai lived as we did seventeen years after the Communist Party took over China. In this city of ten million, perhaps only a dozen or so families managed to preserve their old lifestyle, maintaining their original homes and employing a staff of servants. The Party did not decree how the people should live. In fact, in 1949, when the Communist army entered Shanghai, we were forbidden to discharge our domestic staff lest we aggravate the unemployment problem. But the political campaigns that periodically convulsed the country rendered many formerly wealthy people poor. When they became victims, they were forced to pay large fines or had their income drastically reduced. And many industrialists were relocated inland with their families when their factories were removed from Shanghai. I did not voluntarily change my way of life, not only because I had the means to maintain my standard of living, but also because the Shanghai municipal government treated me with courtesy and consideration through its United Front Organization. However, my daughter and I lived quietly, with circumspection. Believing the Communist Revolution a historical inevitability for China, we were prepared to go along with it.

The reason I am so often carried back to those few hours before midnight on July 3, 1966, is not only that I look back with nostalgia upon my old life with my daughter but mainly that they were the last few hours of normal life I was to enjoy for many years. The heat lay like a heavy weight on the city even at night. No breeze came through the open windows. My face and arms were damp with perspiration, and my blouse was clammy on my back as I bent over the newspapers spread on my desk reading the articles of vehement denunciation that always preceded action at the beginning of a political movement. The propaganda effort was supposed to create a suitable atmosphere of tension and mobilize the public. Often careful reading of those articles, written by activists selected by Party officials, yielded hints as to the purpose of the movement and its possible victims. Because I had never been involved in a political movement before, I had no premonition of impending personal disaster. But as was always the case, the violent language used in the propaganda articles made me uneasy.

My servant Lao-zhao had left a thermos of iced tea for me on a tray on the coffee table. As I drank the refreshing tea, my eyes strayed to a photograph of my late husband. Nearly nine years had passed since he died, but the void his death left in my heart remained. I always felt abandoned and alone whenever I was uneasy about the political situation, as I felt the need for his support.

I had met my husband when he was working for his Ph.D. degree in London in 1935. After we were married and returned to Chongqing, Chinas wartime capital, in 1939, he became a diplomatic officer of the Kuomintang government. In 1949, when the Communist army entered Shanghai, he was director of the Shanghai office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kuomintang government. When the Communist representative, Zhang Hanfu, took over his office, Zhang invited him to remain with the new government during the transitional period as foreign affairs adviser to the newly appointed mayor of Shanghai, Marshal Chen Yi. In the following year, he was allowed to leave the Peoples Government and accept an offer from Shell International Petroleum Company to become the general manager of its Shanghai office. Shell was one of the few British firms of international standingsuch as Imperial Chemical Industries, Hong KongShanghai Banking Corporation, and Jardinesthat tried to maintain an office in Shanghai. Because Shell was the only major oil company in the world wishing to remain in mainland China, the Party officials who favored trade with the West treated the company and ourselves with courtesy.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Life and Death in Shanghai»

Look at similar books to Life and Death in Shanghai. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Life and Death in Shanghai and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.