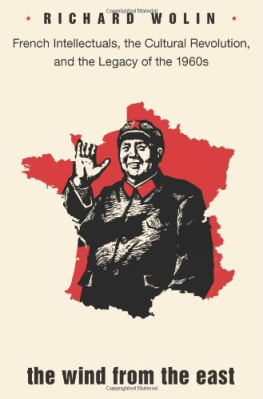

The Wind from the East

O THER B OOKS BY R ICHARD W OLIN

Walter Benjamin: An Aesthetic of Redemption

The Politics of Being: The Political Thought of Martin Heidegger

The Heidegger Controversy: A Critical Reader

The Terms of Cultural Criticism: The Frankfurt School, Existentialism, Poststructuralism

Labyrinths: Critical Explorations in the History of Ideas

Karl Lwith, Martin Heidegger and European Nihilism (editor)

Heideggers Children: Karl Lwith, Hannah Arendt, Hans Jonas, and Herbert Marcuse

The Seduction of Unreason: The Intellectual Romance with Fascism from Nietzsche to Postmodernism

Herbert Marcuse, Heideggerian Marxism (coeditor)

The Frankfurt School Revisited and Other Essays on Politics and Society

The Wind from the East

French Intellectuals, the Cultural Revolution,

and the Legacy of the 1960s

Richard Wolin

P RINCETON U NIVERSITY P RESS Princeton & Oxford

Copyright 2010 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

All Rights Reserved

L IBRARY OF C ONGRESS C ATALOGING-IN -P UBLICATION D ATA

Wolin, Richard.

The wind from the east : French intellectuals, the cultural revolution, and the legacy of the 1960s / Richard Wolin.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-12998-3 (hardcover : acid-free paper)

1. IntellectualsFranceHistory20th century. 2. IntellectualsFrancePolitical activityHistory20th century. 3. FranceIntellectual life20th century. 4. CommunismFranceHistory20th century. 5. ChinaHistoryCultural Revolution, 19661976Influence. 6. Mao, Zedong, 18931976Influence. I. Title.

DC33.7.W75 2010

305.5'52094409046dc22 2009041630

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Bembo and Helvetica Neue

Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

F OR MY S TUDENTS AT THE U NIVERSITY OF P ARIS

AND THE U NIVERSITY OF N ANTES, 20052008

There are now two winds blowing in the world: the

Wind from the East and the Wind from the West.

According to a Chinese saying: either the Wind from

the East will triumph over the Wind from the West,

or the Wind from the West will triumph over the

Wind from the East. In my opinion, the nature of the

present situation is that the Wind from the East has

triumphed over the Wind from the West.

Mao Tse-tung

Contents

Prologue

If you can remember anything about the sixties,

you werent really there.

Paul Kantner, Jefferson Starship

According to an oft-cited maxim, all history is the history of the present. Try as they might, historians are incapable of abstracting from contemporary issues and concerns. In fact, were they to do so, their work would surely reek of antiquarian sterility. At best, historians can make their biases clear to ensure they do not exercise an overtly disfiguring influence on their presentations and findings.

The presence of the past is especially true of the 1960s. Analysts and commentators have heatedly debated their meaning and import, but nearly all agree that the decade was a watershed. Whatever their ultimate meaning, the 1960s were a caesura that signified the impossibility of returning to the status quo ante. Thus, today the 1960s remain an inescapable rite of passage for those who seek to fathom the nature of the political present. First, their range and extent was genuinely international. In an age of instantaneous, mass communication, virtually no corner of the globe could remain immune from their influence and legacy. Second, the decades effects, rather than being confined to one specific manifestation or mode, were, to invoke French anthropologist Marcel Mauss, a total social phenomenon. The 1960s and their aftereffects influencedand left permanently transformedthe realms of politics, society, fashion, art, and music.

By the same token, it would be impossible to deny that the 1960s have also become historical. Thus the decade has provided fertile ground for interpreters who are seeking to distill and comprehend the origins and bases of contemporary politics and society. Yet, as history, the 1960swhose study threatens to metastasize into another academic growth industrypossess a temporality with a peculiar and profound bearing on the historical present. As such, as a cultural and political phenomenon, the decade remains a pivotal way station on the road toward comprehending who we are and what we would like to become. Hence, to contribute to the historicization of the 1960s is at the same time a method of coming to grips with the history of the present.

According to one celebrated maxim, the 1960s are an interpretation in search of an event. Indeed, a dizzying vortex of interpretations has emerged seeking to fathom and clarify what transpired and why. Having both studied these events and lived through them as a youth (although, admittedly, many memories remain enshrouded in a Hendrix-esque purple haze), at this point, when asked about their ultimate meaning, I am often tempted to fall back on Chinese premier Zhou En-lais immortal response when asked to comment on the historical import of the French Revolution: Its too soon to tell.

Yet, if pressed to define the rational kernel of the 1960s, I would say that it was quite simply the era that rediscovered the virtues of participatory politics. The 1950s had witnessed the triumph of political technocracy. At the time, it had become an intellectual commonplace that government by elitesin most cases, white, male eliteswas preferable to the perils and risks of popular participation. Political mobilization from below was viewed as irrational and untrustworthy, a prelude to totalitarianism in either its right or left variant. The 1950s were a decade when the so-called welfare-warfare state was ascendant, culminating in the debacle of Vietnam and kindred foreign policy disasters that often resulted in massive and abhorrent human rights violations. (Sadly, in many cases, the promissory note on such violations remains past due.) In the United States and elsewhere, the 1960s signified an attempt to wrest control of the political from elites: to counter the ills of technocratic liberalism via recourse to logics of grassroots political engagement and thereby to restore confidence in basic democratic norms.

But the 1960s were also, significantly, the moment when the valence of the political itself underwent a significant transformation and expansion. Henceforth, politics no longer remained confined to the trappings and rituals of electioneering: registering to vote, canvassing, mass rallies, sound bites, televised debates, and the culminating, frequently anticlimactic, solitary act of the secret ballot. Instead, politics was redefined to incorporate cultural politics. Politics began to include acts of self-transformation and the search for personal authenticity. Citizens realized (and here, the American civil rights movement stands out as Exhibit A) that they were not cut from the same mould. Politics became part and parcel of a new quest for personal identity, a quest that is also reflected in much of the literature of the period, for in the modern world identities no longer arise preformed and ready-made. Instead, they must be created, fashioned, and nurtured. This development helps to account for the new proximity between culture and politics. Today, culture has become one of the primary vehicles of political self-affirmation and group self-expression. Thus, one of the 1960s crucial legacies is the idea of cultural politics. The lesson we have learned is that the