I am most obliged to all those who have kindly accepted my invitations for interviews, which are very important to ground my analyses and open up my horizons. This book was also made possible by many who generously lent a helping hand with my research at different stages, including Joseph Li, Tang Ching-kin, Zhang Chuntian, Wei Ping, Wu Weimian, Teresa Chan, Nocus Yung, and Donald Yeung. Those distinguished PRC scholars who have provided me valuable information and research comments include Jin Dalu and Zhang Lianhong at Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, Cao Chunsheng at Jingdezhen Ceramic Institute, Xie Shaocong and Ching Mei-bo at Sun Yet-sen University. Independent ceramic scholar Ken Lo, Director Lou Tai Seng of Museu de Arte de Macau, Mr. Liang Yanlan of Guangdong Cantonese Opera Theatre, and Director Yang Peiming of Shanghai Propaganda Poster Art Center are all very kind to have shared their professional knowledge with me. Thanks from the bottom of my heart also to my cousin Guo Jianling for driving me from Nanchang to Jingdezhen, Stella Qu for bringing me to the Jianchuan Museum Cluster, and Yang Yang for connecting me to the National Ballet of China. Daisy Yuan, Irene Guo, and Edward Luper also pointed me in interesting research directions.

I thank Denise Ho, Harriet Evans, Chris Berry, Paul Clark, Ban Wang, Yiching Wu, Chris Connery, and Catherine Yeh for sharing with me their profound knowledge about the Cultural Revolution. I specifically want to thank Rebecca Karl for believing in my works, which I do not at times. Tony Bennett, Margaret Hillenbrand, Andrew Jones, Carlos Rojas, Zhang Chuntian, Qian Ying, and Li Jie have kindly invited me to their institutions to talk about my Cultural Revolution research. I thank them and all those who have generously shared their comments and knowledge at my talks. I am blessed by the Universities Service Centre for China Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, whose rich collections and vibrant lunch talks witnessed and nurtured every single step of my research. I also thank Librarian He Jianye of C.V. Starr East Asian Library of UC Berkeley for introducing me to their rare collection. Hong Kongs Research Grant Council (General Research Fund) and the Chinese University of Hong Kong (Direct Grant and South China Programme Research Grant) offered me generous financial support to conduct this research. I am most grateful to Audrea Lim at Verso for her excellent editorial comments, through which I have begun to understand the subtle differences between being pedantic and being erudite. Obviously I am still learning.

My sons Haven and Hayden let me in on their happy childhoods, which are completely different from my academic life, and the two parallel universes make each other more original, creative, and joyful. My husband KC continues to accept and ignore my incessant forgetfulness, sudden silence, and groundless anxiety with his composure toward the external world. My mother Ng Wing and my late father Pang Ho Ting gave me and my brother their most precious effort to nurture us into dignified and responsible human beings. Only in my family members do I see how I can be myself.

Shorter versions of are based on two of my previous essays, which appeared in Challenging (the) Humanities, edited by Tony Bennett (Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2013) and Visualizing China: Moving and Still Images in Historical Narratives, edited by Christian Henriot and Wen-hsin Yeh (Leiden: Brill, 2012) respectively, although the chapters in this book are substantially different from the previous articles.

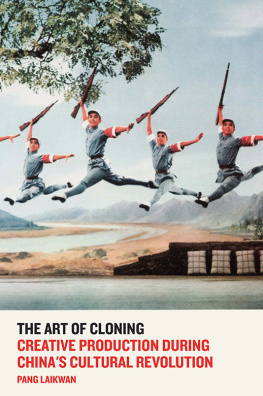

I f we compare todays China with the country of fifty years ago, it is not difficult to reach the conclusion that Maoist China produced identical subjects. In the 1950s, the Chinese people were already described as blue ants: they all dressed the same, looked the same, and walked the same. Entering the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, which officially began in 1966, this uniformity seemed to extend from the look to the mind, and people thought and acted in ways that connected them with Mao and unified them. It could be seen as an immaculately monotonous world, one full of repetition and imitation. There were clearly people who were out of line with the mainstream, but the price was often too high, and the pressure too intense, for anyone to flaunt difference. Indeed, many displayed very little resistance against the call for uniformity.

From the outside, it is easy to conclude that this uniformity resulted from fanatical politics, an authoritarian government, and a compliant people with a submissive history. This book will explore all of these issues. However, a closer look reveals that this world of uniformity also offered a diversity of cultural experiences and an obscure sense of freedom. During the Cultural Revolution, ordinary Chinese citizens read many books, traveled to different parts of the country, and engaged in various kinds of cultural production. Their lives were not necessarily more deprived or boring than ours, which are diverse mainly because of different versions of pseudo-individualized cultural consumption. Other than the models of trauma and victimization, how can we account for the individuals who conceptualized themselves as autonomous, despite being highly conformist?

Let me begin with an example. Those who grew up during the Cultural Revolution are now in their late fifties or sixties, and among the more educated we find a common nostalgia for their Cultural Revolution reading experiences. Writers from Han Shaogong to Bei Dao, from Zhu Xueqin to Wei Guangqi, and from Wang Anyi to Zhi An all meticulously recount the books they read and how they read them. Through an intimate description of their book lists, these intellectuals demonstrate the autonomy they were able to exercise in an age of extreme control. They also prove an insight into their intellectual independence, realized through their unique efforts to acquire knowledge without any institutionalized schooling. But behind the discrete accounts of epistemological pursuit, a common pattern of emotions can also be found among these stories, characterized by similar excitement and pleasure among the authors about reading, exchanging, and copying books. Recent research shows that a vigorous independent reading culture developed during the Cultural Revolution, and people were exposed to a wide variety of books circulating around. But there was also considerable overlap in the books the educated youth read, such as the so-called yellow-cover or grey-cover books published in the early 1960s for the partys internal reference only. These banned books they read with such excitement were those already preselected by the party. In these personal tales, we can find a subtle dialectics of individuality and collectivity: on the one hand, below the surface of extreme uniformity there was enough space available for individuals to articulate their personalities; however, on closer inspection, these so-called individualities were not that distinguished from each other. Even these rebellious acts were conducted within a highly homogenous environment, and each persons private experiences and independent actions were also shared widely among the same generationthese individuals are both unique and not so unique.