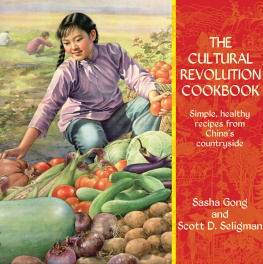

THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION COOKBOOK

Copyright 2011 Sasha Gong and Scott D. Seligman

ISBN-13: 978-988-19984-6-0

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in material form, by any means, whether graphic, electronic, mechanical or other, including photocopying or information storage, in whole or in part. May not be used to prepare other publications without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information contact .

Published by Earnshaw Books Ltd. (Hong Kong).

Table of Contents

A Revolution is Not a Dinner Party

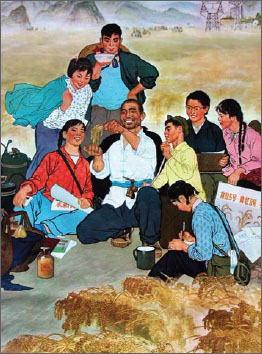

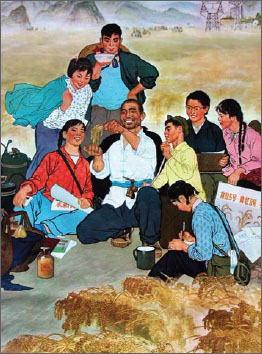

Take the classroom into the fields, 1975. Open the school doors and take the classroom into the fields was a mid-1970s movement that brought university students and professors into factories and farms to learn firsthand from workers and peasants.

It was Chairman Mao Zedong (18931976) who famously wrote this line, and most of those forcibly sent down to the countryside during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976 would surely agree. Most came to feel that leaving their education and professions behind to work side by side with the peasants was a tragic waste of their productive years and an unmitigated disaster for China.

It was, in fact, both of those things. But for many it was not completely devoid of redeeming aspects. Hard toil in the communes was not pleasant, but it was a learning experience for the many city dwellers sent down during that tumultuous decade. And like it or not, it shaped their lives and remains to this day a vital part of their personal histories.

Living among the peasants was difficult, and food was seldom abundant. But those who experienced it learned to make do with what there was. They learned to cook with the fresh, wholesome foods that were in season and to conserve scarce fuel by flash-cooking over a very hot flame. And they learned to prepare remarkably tasty and healthful dishes with enough nourishment to sustain them through long, arduous days in the fields.

The many awful accounts of the bad times, during which people were forced to eat insects and tree bark, were true, but they dont tell the entire story. Living in the countryside made many into frugal cooks who learned to get the best flavors out of low-calorie foods, devoid of chemical preservatives, fresh from the fields and ponds.

These are their recipes. They dont require exotic ingredients; everything you need can be found in a reasonably well-stocked grocery store. The step-by-step instructions are easy to follow, and substitutions are suggested where appropriate. The Cultural Revolution was, indeed, no dinner party, but that didnt stop many Chinese cooks from working culinary wonders with what they did have readily available: the fresh, local, healthy foods of the countryside.

A Personal Story

By Sasha Gong

Guangzhou, 1962: I Learn to Cook

I started my cooking career at age six. The year was 1962, and I had just entered elementary school. My parents, both faculty members at a college in Guangzhou (Canton), had to work from seven in the morning until 11 at night, so nobody was home to take me to school, and nobody was there when I got home. My mother gave me instructions on how to whip up breakfast and dinner for myself on our small, coal-burning stove. Breakfast was normally a bowl of noodles with a sprinkling of salt and soy sauce, and a typical dinner might be a bowl of rice with boiled vegetables or an occasional egg. With just a few drops of cooking oil, a fried egg tasted heavenly if one was lucky enough to get ones hands on one. Just a single egg could make my day.

Me at age five. We were living in Guangzhou.

China was just coming out of its worst famine ever, a disastrous consequence of the Great Leap Forward, an exercise in accelerated central planning gone amok that created shortages of nearly everything people needed to live. If coal was hard to get, meat was even harder. One of my brothers, aged five at the time, was questioned in kindergarten about his view of communism, which had of course been held up to all of us as an ideal society. His answer? Communism is when we all have meat to eat at every meal! Most of the time, of course, it meant precisely the opposite. To supplement our meager rations of meat, in fact, I was assigned the duty of feeding four rabbits being raised on our balcony. I gave them fresh grass harvested from the school yard, and when they reached maturity, they were a welcome addition to the family dinner table.

Rabbits werent the only food people raised at home. During those lean years, most food was rationed, and urbanites like us grew whatever we could in our tiny apartments, on our balconies or if we were lucky on small plots of land. People raised chickens, guinea pigs and ducks in their homes and grew chives, squash, eggplant, cucumbers and cabbage. Only grain was off-limits; the government insisted on a monopoly on rice, wheat and other grains, for which you had to line up at city markets and wait for hours before you could get your monthly allotment in exchange for cash and a ration coupon.

Xinqiaohe, Hunan Province, 1965: We are Sent to the Countryside

In 1965, my siblings and I were sent to live with my grandparents because my parents found it too onerous to care for us. Unfortunately, just two months later, my grandfather, a World War II hero who had fought the Japanese in the 1940s, got into political trouble. He was accused by the government falsely of being a counter-revolutionary, and as a consequence lost not only his job, but his right to live in the city, which even today is considered a privilege in China. He was forced to return to the small village in Hunan Province where he had been born, and which he had left in the 1920s. As members of his household, my grandmother, my brothers and sister and I had to go along with him.

Our entire family six in all was assigned to a 200-sq. ft. room in a three-room house in the village of Xinqiaohe. Our room came complete with a small pit in which a few chickens slept. Half the kitchen, which we shared with another family, was taken up by a large stove with two burners. There was a huge wok and a smaller pot that kept water warm for bathing and drinking. This was fed from a large water tank (which we children filled every day, bucket by bucket, from a local pond). There was also a wooden table with a slice of a tree trunk we used as a cutting board and a few miscellaneous utensils a spatula, a ladle and a large pair of chopsticks.

The village had neither a store nor a market, and the closest grocery was a three-hour hike away. So except for a very few items such as salt and soy sauce, virtually everything we ate was produced nearby. Eggs came from the hens pecking for morsels under our dinner table, or for bugs outside. We learned that when a young hens face turned red, it meant she was about to begin egg production. Occasionally, a hen would refuse to come out of the pit. Two weeks later, she would show up with a dozen noisy chicks, proudly strolling through the neighborhood.

Next page