The Appearing Demos

The Appearing Demos

Hong Kong During and After the Umbrella Movement

Pang Laikwan

University of Michigan Press

Ann Arbor

Copyright 2020 by Pang Laikwan

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by the

University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

First published February 2020

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pang, Laikwan, author.

Title: The appearing demos : Hong Kong during and after the Umbrella Movement / Pang Laikwan.

Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019039019 | ISBN 9780472131785 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780472037681 (paperback) | ISBN 9780472126507 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Umbrella Movement, China, 2014. | Political participationChinaHong Kong. | Protest movementsChinaHong Kong. | Sociology, UrbanChinaHong Kong. | Politics and cultureChinaHong Kong. | Hong Kong (China)Politics and government1997

Classification: LCC JQ 1539.5. A 91 P 36 2020 | DDC 322.4/4095125dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019039019

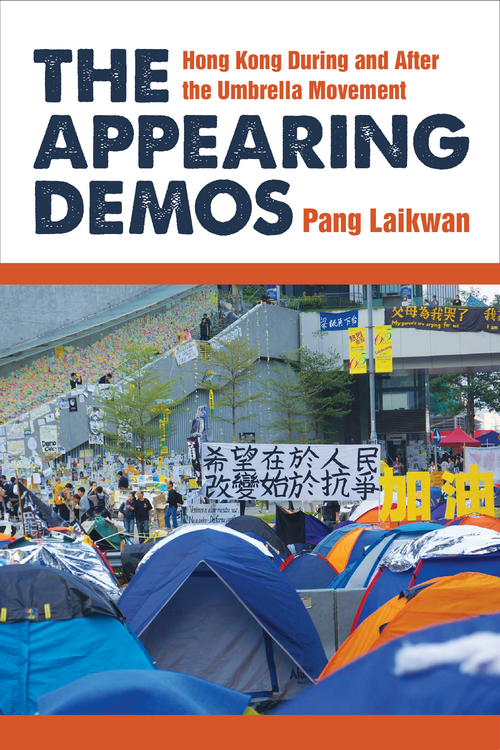

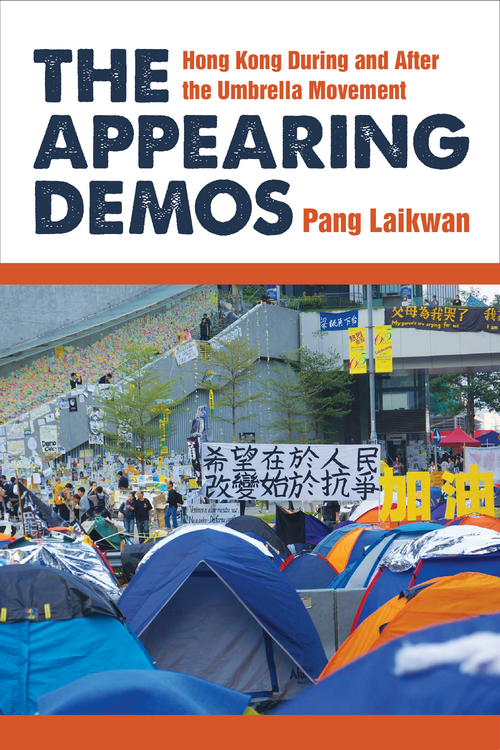

Cover photograph provided by Umbrella Movement Visual Archives & Research Collective.

Contents

Digital materials related to this title can be found on the Fulcrum platform via the following citable URL: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11357429

Page vi Page vii

So many people around me engaged in the Umbrella Movement in one way or another, and my own theorizations are fundamentally shaped by theirs. The central concern of this book, cohabitation, is less an abstract theoretical concept than it is the wisdom, fortitude, and tenderness I have learned from them. Living in Hong Kong over the last few years hasas Rainer Maria Rilke (2000, 35) writesbeen living the question: At present you need to live the question. Perhaps you will gradually, without even noticing it, find yourself experiencing the answer, some distant day.

First and foremost, I would like to thank all my interviewees for being so willing to share their experiences and reflections with me; these provided the foundation for my deliberation and writing. They are, in alphabetical order and not all real or full names: Brother Four, Elaine Chan, George Chan, Chan Hau-Chun, Chan Kin-Man, Chan Tze-Woon, Valerie Cheng, Fernando Cheung, Agnes Chow Ting, Alex Chow Yongkang, Donna Chu, Ling Chu, Chui Chi-Yin, Helen Fan Lok-Yi, Ho Sik-Ying, Sunny Huang, Rita Hui Nga-Shu, Irene, Ivy, Mary Ann King Pui-Wai, Glacier Kwong Chung-Ching, Lee Wai-Shing, Jeffrey Ngai, Horatio Tsoi, Agatha Wong, Big Uncle Wong, Joshua Wong, Old Lady Wong, Wong Ching-Fung, Kengo Yip, Wan King-Fai, and Young.

I thank Ray Lai and Sam Cheung for their remarkable assistance in locating relevant research materialsthey are outstanding young scholars, and it is my blessing to have benefited from their support. I thank Howard Yu and Joey Chung for transcribing many of the interviews, and Carol Chow for sharing with me some of her great photographs. I also thank Chong Suen for her suggestion of the book cover photo and her aesthetic tips. I am most obliged to Chan Sin-Yuk, who arranged and went with me to many of the interviews, infusing the project with her enthusiasm and curiosity. I also Page viii want to thank Cheung Chui-Yu, whose contributions to my research are everywhere. The unyielding trust and friendship of Janet Pang and Nocus Yung are a godsend to me. The intellectual insights of Joseph Li, Sampson Wong, Gary Tang, and Ko Chun-Kit have also inspired my analysis in magical ways. I am so lucky to be able to learn from all these compassionate and intelligent young people. I also wish to thank the Research Grant Council in Hong Kong for the generous General Research Fund it offered to support this research, as well as the Faculty of Arts of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) for the publication subvention support.

I thank Lisa Rofel, Michael Curtin, John Armitage, Ryan Bishop, and Shuang Shen for believing in this project and giving me much needed encouragement. I also thank Harriet Evans, Derek Hird, Margaret Hillenbrand, Jie Li, Alexander Zahlten, Marc Steinberg, and Joshua Neves for bringing me to the University of Westminster, the University of Oxford, Harvard University, and Concordia University to talk about my research. Earlier and shorter versions of chapters 3, 4, 7, and 8 were published in Cultural Politics, Social Text, global-e, and Verges. The comments and questions that I received on these occasions shaped the final version of the book in fundamental ways.

I am most humbled by the comments of the three anonymous reviewers of this book manuscript, who generously shared with me their most supportive and productive insights and opinionsthe final form of this book is partly theirs. I must also thank Christopher Dreyer and Mary Francis of the University of Michigan Press for trusting and caring about this project since the very first day, and Susan Jarvis, who provides not only the most professional editing support but also gentle friendship.

My most faithful love remains with KC, Haven, and Haydenthey complete me.

Page 1

Higher than actuality stands possibility.

Martin Heidegger

A S THE THIRD WEEK of Hong Kongs Umbrella Movement approached, things began to slow down in the occupied roads in Admiralty, Mong Kok, and Causeway Bay: the Hong Kong Special Administrate Region (SAR) government did not show any gestures of compromise, yet the occupants also did not feel any immediate threats of forced eviction. The Umbrella Movement, which began on September 28, 2014, continued but also drifted aimlessly, and some occupants began to settle into a new life of continual protest. Some of the Mong Kok occupants put together an event to celebrate the establishment of their New Mong Kok Village, and a ping-pong table was also installed on Nathan Road, luring occupants and passersby to stop by and play a game in this space originally intended for cars only (figure 1). People began to line up, and spectators gathered and cheered. Mahjong tables and hot-pot parties were set up, showing that some people had decided to enjoy the occupation. But a few occupants found the lightness too much to bear and rebuked these activities as carnivalesque. Knowing that blocking the citys major roads was causing a lot of inconvenience and irritation to many, these exhorters warned their fellow protesters not to give the impression that they were taking to the streets just for fun. People started to argue, challenging the intentions and political correctness of one another. The ping-pong table silently disappeared.

As the Hong Kong Occupy movement became more protracted, debates about strategies and public image continued to arise and intensify, manifesting in many different forms. The ping-pong table could be seen as one of the Page 2 first signs of the movements internal discord, but it also revealed some fundamental features of this movement. A ping-pong match could certainly be considered an analogy for the political stage, where antagonistic political forces clashed, but ping-pong is also one of the most easily handled and amiable ball games. Ping-pongs portable table, light paddles, and small balls make it a leisure activity that is popular across diverse ages and cultures. Facing each other across a table, opponents can spend a lot of time in the game just chatting and hanging around. While table tennis is a competitive sport involving individual players driven to win, the ping-pong table on Nathan Road revealed that this dissident movement was also a communal event, allowing a crowd to gather and appear. Playerswho at the same time were spectatorswaited and watched until their turn came. The game engenders a sense of community by engaging people, who relate to each other in gritty or relaxed ways, through playing and watching, cheering or booing.

Next page