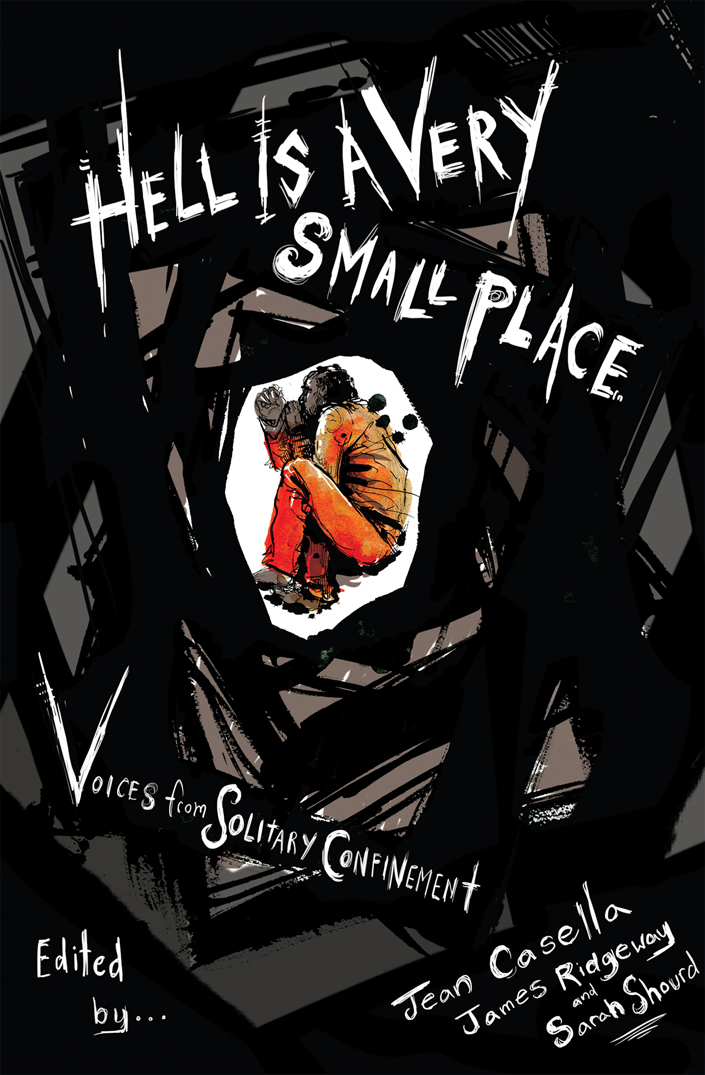

Compilation and headnotes copyright 2016 by Jean Casella, James Ridgeway, and Sarah Shourd

Preface copyright 2016 by Sarah Shourd

Introduction copyright 2016 by Jean Casella and James Ridgeway

Afterword copyright 2016 by Juan E. Mndez

Individual essays copyright 2016 in the names of their authors

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Writing Out of Solitude by Shaka Senghor is excerpted from an essay that originally appeared in Fourth City: Essays from the Prison in America, edited by Doran Larson (Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2014).

Portions of Dream House by Herman Wallace originally appeared in The House That Herman Built, by Jackie Sumell and Herman Wallace (Akademie Schloss Solitude: 2006). Reprinted by permission of Jackie Sumell.

Excerpt from September 1, 1939 by W.H. Auden from Another Time, published by Random House. Copyright 1940 W.H. Auden, renewed by the Estate of W.H. Auden. Used by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd.

Psychiatric Effects of Solitary Confinement by Stuart Grassian is excerpted from an article published in the Washington University Journal of Law and Policy 22 (January 2006).

How to Create Madness in Prison by Terry Kupers is adapted from a chapter in Humane Prisons, edited by David Jones (Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing, 2006).

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2016

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

ISBN 978-1-62097-138-3 (e-book)

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Book design and composition by Bookbright Media

This book was set in Bembo and Avenir

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For those who find the courage to break the silence

For those too shattered to do so

And especially for Billy

Contents

Table of Contents

Guide

SARAH SHOURD

AT SOME POINT YOURE GOING TO SNAP. THIS MIGHT BE AFTER ONE week or one year, depending on how youre wired. At first the scream ripping through your throat is a welcome release. You ball up your fists and pound on your cell door, vomiting every expletive you can think of. You damn the guards to hell along with the system and every person who ever cursed your life. A guard yells at you to shut the fuck up. You tell him to fuck himself and scream louder, choking on your own snot and angry tears. After a while you collapse, curl up on the hard floor of your cell, and enjoy a few of the best hours of sleep youve had in a very long time.

When you open your eyes again your system is immediately flooded by the same instinctual rage. You begin pounding on the steel door of your cell, but this time when you scream no one shouts back. Hours later, when the lunch cart rumbles by you find youve been skipped. You start up againyour fists raw, your knuckles chaffed and bloody. When the guards do arrive they come with tear gas, batons drawn. They come to make you choke on your screams.

Days later youve appeared to calm down. To settle in. Yet the scream doesnt stop. You try not to hear it as you brush your teeth, take your meds, force yourself to do push-ups, or attempt to focus on reading a magazine. As long as youre stuck in this coffin that silent scream becomes the backdrop of every moment of your waking life. It could last a month, a year, a decade, or the rest of your life, yet no one will ever hear it but you.

I spent 410 days in solitary confinement while being held as a political hostage by the Iranian government from 2009 to 2010. Upon returning to the United States I discovered that this draconian practice, antithetical to any pretense of rehabilitation, is used as a routine control mechanism in U.S. prisons, far more extensively than in any country in the worldor any country in history.

In solitary confinement, a grey, limitless ocean stretches out in front of and behind youan emptiness and loneliness so all-encompassing it threatens to erase you. Whether youre in that world a month, a year, or a decade, you experience the slow march of death. Day by day you lose your connection to everything outside the prison walls, everything you once knew and everything you once were.

People in solitary commit suicide at a much higher rate than any other incarcerated population. Some go visibly crazy, whipping their skin raw, eating their own feces, or cutting off their genitals. Others adjust, showing no outward signs of insanity. But what if the adaptation is itself proof of how effective this form of torture can be? What if the silent scream internalizes whats being done to you, making you identify with, or even become, your own torturer?

As you will read in this anthology, the conditions and so-called privileges allotted to people in solitary confinement in the United States vary from state to state, facility to facility, and prisoner to prisoner. Some cells have small windows. Prisoners can usually communicate with each other, sometimes by shouting through a wall, and sometimes by sending clandestine notes. Many are allowed books, television, pen and paper, photographs, and limited access to a phone, email, canteen, and no-contact visitation. Though some isolation units in U.S prisons are filthy and dark, harking back to medieval dungeons, others are hyper-modern, where cell doors are opened and closed remotely by guards you may never even see.

Over time you experience a social death. You wake up every morning to the reality that if everyone you knew hasnt already forgotten you, chances are they eventually will. Even if you do get out, you fear the you who has walked through the world since the day you were born might be irrevocably damaged, changed, and unrecognizable. If days, weeks, months can pass without a single person on the outside seeing or (as far as you know) even thinking about youwhos to say you even exist?

While held hostage in an Iranian prison, it was six months before I was allowed a phone call. At times, I was reduced to an animal existence, pacing back and forth eight or ten hours at a time, eating with my hands, crouched by the food slot in my door listening for something, anything, to remind me that I was still in the world of the living. Sometimes I wouldnt eat or move for days; at other times, I screamed and beat at the walls of my cell until my knuckles bled.

The misery of prisoners confined to the hole or box in U.S. prisons is often compounded by physical abuse: being beaten and raped by sadistic guards, subjected to freezing-cold temperatures, fed rotten food, and left to die without medical care. This alone would be enough to break a human being, but I would argue that the crueltythe tortureof solitary confinement targets a part of us perhaps more essential than even our physical bodies: the part that makes us human.