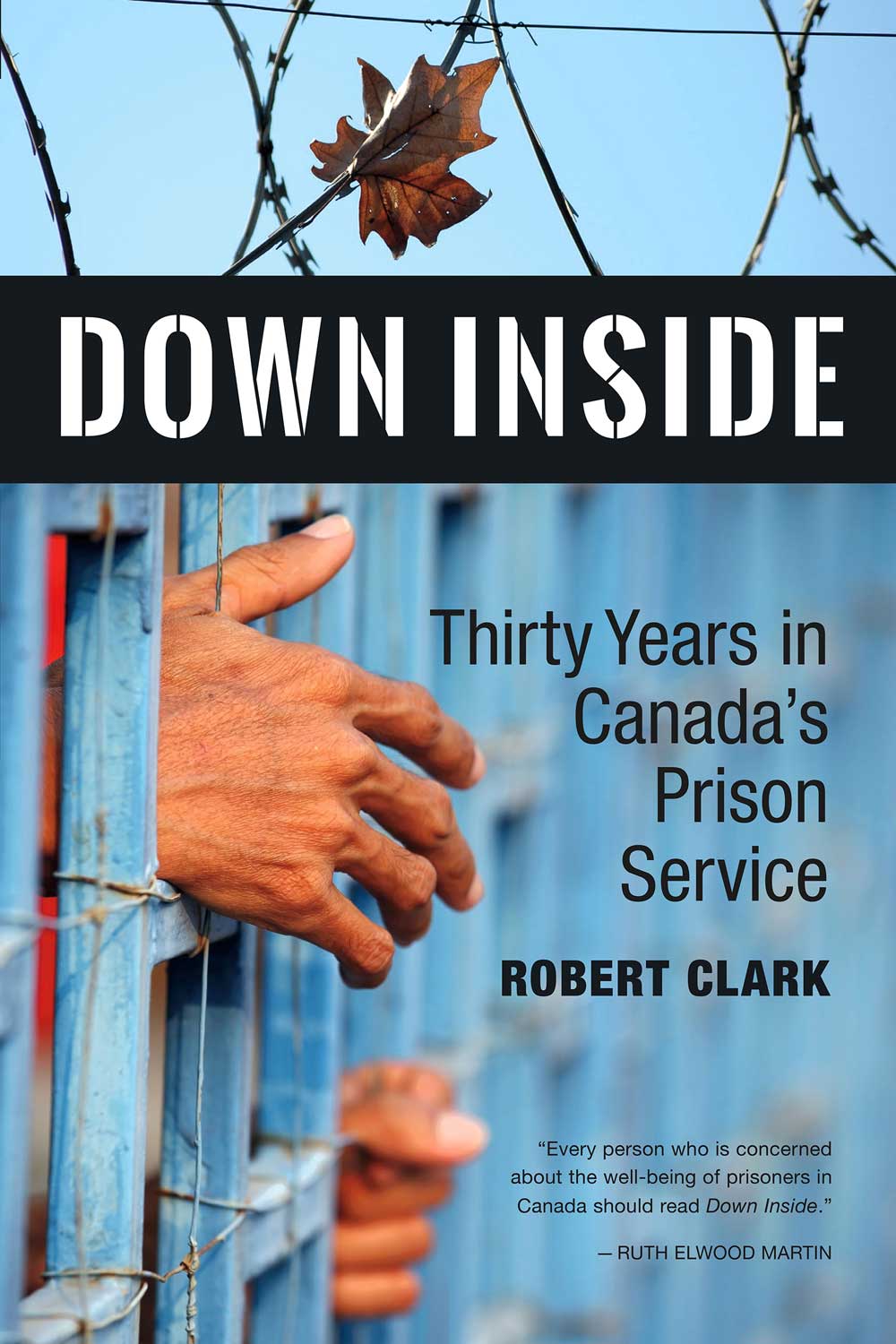

Robert Clarks candid writing about the inner workings of federal corrections illustrates why things can go so terribly wrong. Robert shows us that a healthier environment results when prisoners feel that they are being treated like human beings. As he concludes, The secret to this complex issue, the key to the lock, is the environment that we create.

Ruth Elwood Martin, Director, Collaborating Centre for Prison Health and Education, UBC, School of Population and Public Health

During his career with Corrections Canada, Robert Clark rose through the ranks of the Canadian prison system from student volunteer to deputy warden. He worked with some of Canadas most notorious prisoners, including Tyrone Conn and Paul Bernardo, and he dealt with escapes, lockdowns, murders, suicides, and a riot. But he also arranged ice-hockey games in a maximum-security institution, sat in a darkened gym watching movies with three hundred inmates, took parolees sightseeing, and consoled victims of violent crimes.

In Down Inside , Clark takes readers into prisons large and small, from the minimum-security Pittsburgh Institution to the Kingston Regional Treatment Centre for the mentally ill and the notorious (and now closed) maximum-security Kingston Penitentiary. A compelling personal memoir and a scathing indictment of bureaucratic indifference and agenda-driven government policies, this book challenges head-on the popular belief that a tough-on-crime approach makes prisons and communities safer, arguing instead for humane treatment and rehabilitation and for an end to the abuse of solitary confinement.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). To contact Access Copyright, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call 1-800-893-5777.

Edited by Jill Ainsley.

Cover and page design by Julie Scriver.

Cover images: (hands) sakhorn38, iStock.com; (leaf) majorosi, iStock.com.

Printed in Canada.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Clark, Robert, 1955-, author

Down inside : thirty years in Canadas prison service / Robert Clark.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-86492-969-3 (softcover).--ISBN 978-0-86492-970-9 (EPUB).--ISBN 978-0-86492-971-6 (Kindle)

1. Clark, Robert, 1955-. 2. Prison wardens--Ontario--Biography. 3. Criminals--Rehabilitation. I. Title.

HV9505.C63A3 2017 365.92 C2016-907049-2

C2016-907050-6

We acknowledge the generous support of the Government of Canada, the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Government of New Brunswick.

Goose Lane Editions

500 Beaverbrook Court, Suite 330

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3B 5X4

www.gooselane.com

This book is dedicated to my wife, Linda, and my children, Stephanie and Adam. If not for their unconditional love and support, this book would not have been possible. I love you all more than I can ever express in words.

In my view, if anything emerges from this inquiry,it is the realization that the absence of the Rule of Law is most noticeable at the management level, both within the prison and at the Regional and National levels. The Rule of Law has to be imported and integrated, at those levels, from the other partners in the criminal justice enterprise, as there is no evidence that it will emerge spontaneously.

Whether prisoners should have certain rights, such as the right to counsel, the right to effective segregation review, to family contacts, to exercise, etc., is for Parliament to decide in compliance with any constitutionally mandated entitlement. One must resist the temptation to trivialize the infringement of prisoners rights as either an insignificant infringement of rights, or as an infringement of the rights of people who do not deserve any better. When a right has been granted by law, it is no less important that such right be respected because the person entitled to it is a prisoner.

Justice Louise Arbour, Commission of Inquiry into Certain Events at the Prison for Women in Kingston , 1996

Contents

Introduction

Hell is the state of the soul after death, but it is also the state of the world as seen by an exile whose experience has taught him no longer to trust the worlds values.

John Freccero, Foreword to Dante, The Inferno , Robert Pinsky, trans.

One of my earliest memories of growing up in Toronto was my parents telling me, Lock the door after we leave. As the eldest of three, this instruction became for me and other urban kids of my generation a mantra for personal safety. Locked doors gave our parents peace of mind when they left us alone. When we lock doors, we feel safer. That is what locks are for.

But locks can make things worse. Locked doors can prevent us from seeing whats on the other side. How do we know its dangerous? What if were mistaken? And locks can keep out the wrong things, like a chance to explain what really happened to someone who will truly listen. In prison, locks sometimes keep out the hope of being heard at all, of getting a message home, of seeing ones children, of life getting better. Locks can cause people to succumb to resignation over dreams, to rage over co-operation, to death over life. And locking doors is essentially what prison is all about.

If the true goal of prison is to reduce the likelihood of prisoners committing further crimes when released, then it follows that another goal of prison should be to maximize the likelihood of positive change, individually and collectively. This book reveals what really goes on inside Canadas federal prisons as I experienced it first-hand. In telling the stories of my thirty years down inside, I argue that humane treatment is the most effective way of managing a prison safely and creating conditions to rehabilitate prisoners to become productive members of society. The more humane the environment, the safer for all concerned, prisoners and staff alike; my three decades of experience convince me beyond a doubt that this is true. We must begin by unlocking doors and discovering who and what we are really dealing with.

My career in Canadas federal prison system began in February 1980. I was twenty-four years old and had signed a nine-month contract to work at the Joyceville medium-security prison in Kingston, Ontario, replacing an employee in the gymnasium area. I saw the job as a temporary measure until I could find a teaching job in Toronto, which was my home. As is often the case, however, my plans did not work out the way I expected. I ended up staying with the Canadian federal prison service, and over the next three decades I worked inside seven different federal prisons in Ontario, at all three levels of security, including both of the maximum-security prisons in the Kingston area, Millhaven and the now-defunct Kingston Penitentiary. One reason I moved around so much was that I rose through a series of promotions; the other reason was curiosity.

The vast majority of this thirty-year career was spent working right on the front lines, in the cellblocks and other areas where staff and prisoners interacted face to face every day. I was down inside among prisoners and staff in every facet of prison operations. I locked and unlocked cells, completed prisoner counts, and took prisoners to the hole (solitary confinement) against their will. I took four or five prisoners outside the prison on work details by myself, conducted strip searches, and put out fires on the ranges (hallways of cells) following a murder. At Christmas, I allowed some prisoners phone calls home and declined to release others. I played hockey with the prisoners in a maximum-security prison yard and sat in a tower with a rifle overlooking the same yard. I consoled prisoners when their mothers died. I had a prisoner grab me by the throat, and I had my life threatened more times than I can remember. I had coffee poured for me and urine thrown at me. I saw a lot of blood.