About the Book

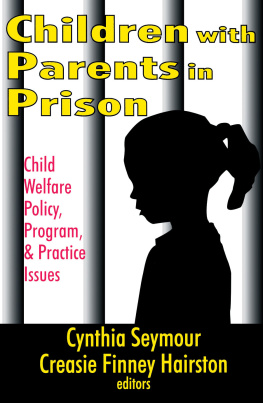

Kerry Tucker seemed to be a typical suburban mother of two, but she had a terrible secret: she had been stealing money from her employers.

When her offence was discovered it was reported to be the biggest white-collar crime committed by a female in Victoria, and she was sentenced to seven years in a maximum-security prison, alongside the states most notorious criminals. Being incarcerated with drug dealers and murderers, however, was not nearly as daunting as having to tell her two young daughters why she was leaving them. The shame was almost unbearable.

As Kerry adjusted to life behind bars, she began to see her fellow inmates as more than simply murderers and drug dealers they became real people with names and broken dreams. And as they opened up to her, she realised that many of these women had violent home lives and were not getting parole simply because they couldnt fill out the paperwork. Horrified, Kerry set about using her skills to represent them. She also began to study.

Today, Kerry has a PhD, advocates for women prisoners, and has been reunited with her daughters. In her inspiring memoir, filled with fascinating stories of life behind bars and shot through with wry humour, she reveals how one womans darkest hour can become a turning point in her life. And how, just perhaps, it can even be the making of her.

To Shannyn and Sarah.

Without you both, tomorrow wouldnt be worth the wait and yesterday wouldnt be worth remembering.

PROLOGUE

Theres a secret nether world under the skyscrapers in the heart of Melbourne. I know because Ive been down there. Every day ordinary people walk on top of it as they pass by the marble-panelled Magistrates Court, the architectural drama of the County Court of Victoria, the imposing sandstone grandeur of the Supreme Court of Victoria and countless buildings in the judicial precinct brimming with law firms and street-level cafes. But few pedestrians know about the labyrinth that exists just a metre or so beneath their feet; nor could they imagine the tide of human wreckage that flows through its hidden passageways day in, day out. Im damned sure none of them could have known I was entombed under the footpath, how I ended up there or what was to become of me. I was a prisoner. I didnt exist.

During the eighteen months I was remanded in prison while awaiting sentencing for a crime Ill come to a little later, I came to feel oddly comfortable in this strange, subterranean city. Whenever I was brought into the central business district to face court Id plunge underground into a vast garage, usually with a clutch of other prisoners, in a fortified steel wagon dubbed the Brawler. Once herded out by Corrections Officers, I hardly caught a glimpse of natural light for the rest of the day. If youre an inmate, the beacon of justice flickers out of fluorescent tubes.

The sunken caverns are linked by a network of hallways that burrow beneath the busy streets and tramlines, connecting the various court houses and ancillary services to one another. Corridors snake off to conference rooms, administration centres, a fully staffed medical facility and, of course, cells. Here men and women of varying degrees of culpability and criminal pedigree languish until summoned to the wooden docks of the courtrooms in the real world upstairs.

After one short appearance in 2003 I was escorted from the Magistrates Court back underground and locked in a cell to wait for the Brawler to cart me back to the maximum-security prison on the outskirts of Melbourne that had become my home. Glancing up, I noticed a steel grate through which a ray of sunlight trickled into the cell. Then I saw shapes moving outside; legs and feet flashing by. When I craned my neck I could clearly see the footpath of William Street and the world Id been removed from more than a year earlier.

What would they think if they knew there was someone locked in a cage down here looking up at them? I wondered. Would they get down on their hands and knees and try to talk to me? Would they care? What would they say to me? How would I introduce myself? Would I tell them I had once been just like them?

As I watched Melbournians hurry past my bunker I became transfixed by a pretty woman whose heel had become stuck in one of the footpaths steel grates. Time slowed down and as she bent down to free her trapped shoe my mind took a perfectly sharp, detailed photograph of the moment. I can still see the stitching on her shiny black stiletto heels and the fabric of her tan-coloured skirt. I liked the way it flared, as if shed just stepped out of the 1950s. Boy, I really loved that skirt.

A second later she was free again; heels clicking purposefully as she strutted down William Street. Wheres she going? I wondered. Is she heading home? Is she married? Whats her husband like? Does she have children? Maybe she has little girls like I do? Will she walk through her front door tonight, grab them, smooch them and bundle them into a bathtub full of fragrant bubbles? Oh, how I missed my own darling cherubs, Shannyn and Sarah.

The smell of their skin and hair, the softness of their little paws in mine. Their smiles. Their tears. Their voices. Their bath time. Their need for Mummy. Their very souls.

I had to be careful reminiscing was a dangerous indulgence. If I allowed myself to touch my purest emotions about my children the anguish, longing, guilt, pain and regret I risked being totally overwhelmed and losing the mental strength to make it through the years of prison that stretched ahead of me. Id already come too close for comfort a couple of times.

The familiar metallic clank of a key in the oversized lock brought me back to reality. OK, time to go, the Corrections Officer announced flatly as the cell door was opened. The Brawler was fuelled up and about to depart the underworld to take me back to purgatory on the loneliest fringe of the city. There would be no husband and kids waiting when I got there, no welcome-home glass of vino. Instead Id be eating sandwiches behind razor wire with a woman whod stabbed her husband to death and another whod suffocated her children with a pillow.

As I lay awake on my prison mattress that night I silently reaffirmed the vow Id made to my girls and to myself over and over in the depth of my heart. I will make you proud of me again. One day I will leave this place and you will be proud that I am your mummy. I promise.

It would prove easier said than done.

Forgive me, Father, for I have sinned.

And then silence.

As a little girl Id murmur those mildewed words into my lap once a week, hunched over in the stuffy confessional booth at St Josephs Catholic Church. Nine times out of ten Id leave it at that, unable to go on.

Y-e-e-e-s-s-s ? the priest would eventually prompt me in the hope of unleashing a torrent of heinous admissions from the perplexed and frightened ten-year-old on the other side of the screen.

Well, Father, the thing is I cant actually think of anything that Ive done wrong, Id explain, nervously. Unless you count how I just told you now to forgive me for I have sinned because that was pretty much a lie so maybe thats the sin you can forgive me for?

![HMP Belmarsh - A prison diary. [Volume one. Belmarsh: hell]](/uploads/posts/book/212654/thumbs/hmp-belmarsh-a-prison-diary-volume-one.jpg)