23/7

23/7

PELICAN BAY PRISON AND THE RISE OF LONG-TERM SOLITARY CONFINEMENT

KERAMET REITER

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Amasa Stone Mather of the Class of 1907, Yale College.

Copyright 2016 by Keramet Reiter.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Scala and Scala Sans types by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

ISBN 978-0-300-21146-7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016939153

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To anyone who has lived or worked inside an American prison

CONTENTS

ABBREVIATIONS

| AB | Aryan Brotherhood |

| AC | Adjustment Center (at San Quentin Prison) |

| ACLU | American Civil Liberties Union |

| ADX | Administrative Maximum (a federal prison in Florence, Colorado) |

| ATF | Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms |

| BGF | Black Guerrilla Family |

| CCPOA | California Correctional Peace Officers Association |

| CCR | Center for Constitutional Rights |

| CDC | California Department of Corrections (until 2005) |

| CDCR | California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (after 2005) |

| DSL | determinate sentencing law |

| ICC | Internal Classification Committee |

| IGI | internal gang investigator |

| JLCPCO | Joint Legislative Committee on Prison Construction and Operations |

| La | Eme Mexican Mafia |

| LWOP | life without the possibility of parole |

| NF | Nuestra Familia |

| PLO | Prison Law Office |

| SHU | Security Housing Unit |

| SMU | Special Management Unit |

| USP | United States Penitentiary |

| YACA | Youth and Adult Correctional Authority |

Introduction

When Prison Is Not Enough

ON AUGUST 12, 2015, STEVE NOLEN WAS listening to the radio when mention of a melee in a California prison caught his attention. He rarely thought about California prisons anymore. Decades had passed since he spent every Sunday shuttling between visits with his brother Cornel, at San Quentin, and his brother W.L., a founding member of the Black Guerrilla Family, at Soledad State Prison. Cornel served his time and eventually was released. But W.L. had been shot to death on a California prison yard thirty-five years before, when Steve was a junior in college.

In the intervening years, Steve had established a successful career selling medical devices; he had never set foot in prison except to visit his brothers. But as he listened to news of the melee, he heard a name he recognized. The one prisoner killed in the fight was his brother W.L.s old radical buddy Hugo Yogi Pinell.

I asked Steve, When you heard about Yogi, did it bring back memories of W.L. and

Instant flashback. Instant. I fell off my chair. Literally fell off my chair... And I said, Yogi, still fighting like a young warrior out there. Seventy-one years old. Seventy-one. By then they should have had compassion and let him go. But these guyspeople dont understand these guys... They dont forget.

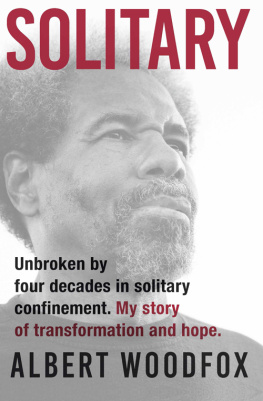

Prison officials never forgot that Pinell was one of six prisoners accused

In 2015, things changed. Prison officials, who make such decisions freely, transferred Pinell from Pelican Bay into the general prison population at California State Prison, Sacramento, as part of an effort to reduce Californias use of long-term solitary confinement. In the Sacramento prison, Pinell hugged his mother for the first time in forty-five years. A few weeks later, two prisoners in their late thirties, both with histories of committing assaults, approached Pinell on the prison yard and stabbed him to death.

Yogi Pinell lived through the entire story of the supermax, or super-maximum-security prison: he was part of the event that inspired its creation, he spent most of his life in one, and he witnessed the first efforts at reformefforts that led to his own death.

At the center of this story is Californias Pelican Bay State Prison, a windowless concrete bunker with hundreds of cells designed for keeping prisoners in total solitary confinement not for days or weeks, as with previous solitary cells, but for years. The Bay opened in 1989. By 2010, more than five hundred prisoners had lived in continuous isolation there for more than ten yearsa decade without a handshake or a hug. Not one of those five hundred was held because of a specific crime committed inside or outside prison. Instead, officials alleged that they were all dangerous gang affiliates, based on their tattoos, books, letters, or drawings. No judge or jury ever reviewed the decision to place any of these men in solitary, or the decision to keep them there. How did isolation like this become routine practice in California and across the United States?

First, no one was watching. Prison officials envisioned the first sleek, automated supermaxes and sited them in out-of-the-way places. In the 1980s, rural towns such as Crescent City, California, located on the Oregon border, vied for the chance to become home to one of the many new prisons popping up all over the United States. Even after Pelican Bay opened in Crescent City, neither citizens nor local legislators knew what kind of prison had been built in their backyard. No politician took credit for imposing its harsh conditions of isolation.

This was a surprisingly overlooked political opportunity in the era of penal populism, Supermajorities of California voters approved billions of dollars in public bonds to finance new prisons, and legislators and governors competed to look the toughest on crime. Today, Pelican Bay is an icon of this mentality, but in 1989 it was functionally invisible. This book introduces a prison official you have never heard of, Carl Larson, who told me that he designed Pelican Bay. Administrative discretion, the supermax story reveals, is even more powerful than penal populism.

No one was watching when prison officials opened Pelican Bay in 1989, but everyone had been watching eighteen years earlier. On August 21, 1971, George Jackson, best-selling author and founding member of the Black Guerrilla Family (then a behind-bars affiliate of the Black Panthers), was shot to death on the San Quentin prison yard. Prison officials said Jackson had been trying to escape from the isolation unit where he was housed. Three guards and two white prisoners also died in the alleged escape attempt. Two weeks later, prisoners at New Yorks Attica Correctional Facility rioted, taking control of the prison for four days. The state police effort to retake the facility killed more than forty people. In the face of this organized, radical violence, prison officials knew that prison was no longer enough. To them, George Jackson proved that new times required new tools of control.

Next page