Scribe Publications

MATESHIP WITH BIRDS

A. H. (ALEXANDER HUGH) CHISHOLM was born in Maryborough, Victoria in 1890, and worked on the Maryborough Advertiser before moving to Brisbane to work on the Daily Mail , and subsequently to Melbourne to edit the Argus . Chisholm worked with C. J. Dennis and published his major work, The Making of a Sentimental Bloke , in 1946. Chisholm died in 1977.

SEAN DOOLEY is a Melbourne comedy writer and author whose first book, The Big Twitch , outlined his attempt to break the Australian birdwatching record. Sean is currently editor of Australian Birdlife , the magazine for BirdLife Australia.

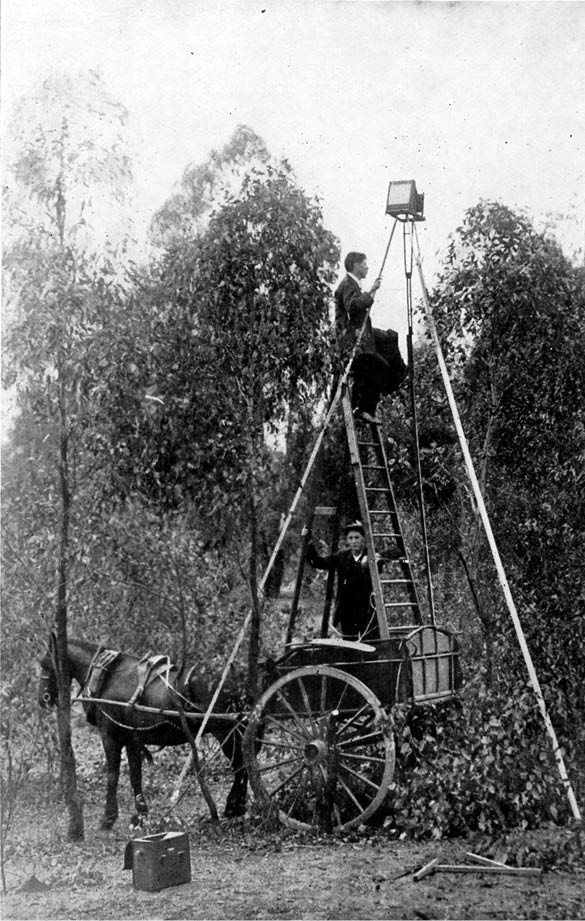

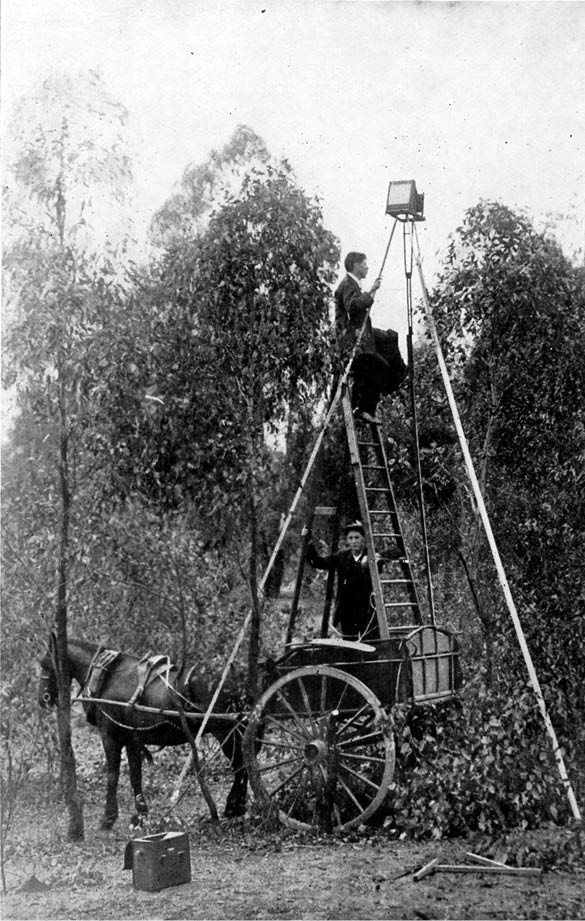

The Author at a Shrike-tits Nest.

(Photo. by N. M. Chisholm.)

Scribe Publications Pty Ltd

1820 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria, Australia 3056

Email: info@scribepub.com.au

First published by Whitcombe and Tombs Limited 1922

Published by Scribe 2013

Text copyright Alec Chisholm 1922

Foreword copyright Sean Dooley 2013

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

While every care has been taken to trace and acknowledge copyright, we tender apologies for any accidental infringement where copyright has proved untraceable and we welcome information that would redress the situation.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data

Chisholm, Alec H. (Alec Hugh), 1890-1977.

Mateship with Birds / A. H. Chisholm.

9781922072245 (e-book)

1. BirdsAustralia.

598.0994

Other Authors/Contributors: C. J. Dennis; Sean Dooley; .

www.scribepublications.com.au

CONTENTS

PART I. A PAGEANT OF SPRING

I.

II.

III.

IV.

V.

PART II. BIOGRAPHIES OF BIRDLAND

VI.

VII.

VIII.

IX.

X.

XI.

TO THE MOTHER AT HOME

FOREWORD

I KNEW ALEC Chisholms name before I knew the name of any other birdwatcher indeed before I knew the names of many birds. When I was eleven, my parents bought me my first real bird book, the 1976 edition of the Readers Digest Complete Book of Australian Birds . In it was a foreword by Alec Chisholm. He was mentioned again in the account of the Paradise Parrot as the last experienced birder to have seen this most beautiful bird before it became extinct (a fact that the dogmatic Chisholm refused to acknowledge right up until his death more than fifty years after his 1922 sighting). That alone fired my budding birdwatchers brain with awe.

It is only in recent years, however, as I have delved into the history of ornithology in Australia as the author of my own books on birdwatching, and as the editor of Australian Birdlife , that I have come to appreciate just what a colossal figure the man referred to as Chis was right up there with John Gould or Neville Cayley in terms of importance to Australian bird study and for providing a voice for Australian birds.

That Chisholm ever came to be held in such esteem is quite remarkable. In an era when the professional ornithologist ruled the roost, Alec Chisholm had no scientific training. It was in his writings, both for ornithological journals and in his innumerable newspaper articles and many books, that Chisholm left an indelible mark.

Chisholm was never a likely candidate to become such a hugely popular and influential writer who counted amongst his circle literary luminaries such as C. J. Dennis (who penned the foreword to the initial publication of Mateship with Birds in 1922) and Dame Mary Gilmore. Born in the central Victorian goldfields town of Maryborough, Chisholm left school at the age of twelve. After stints as a delivery boy and coach-builders apprentice, he almost fell into journalism through his passion for birds.

While his observations of birds encountered in his bush wanderings first started to appear at a precociously young age in journals such as The Emu , it was the publication of his first story in a general newspaper a passionate exhortation to stop the slaughter of egrets for plumes used for decoration in the millinery trade that set his career as a journalist rolling. It was to be a long and distinguished career as a reporter and editor for newspapers in three states, including stints as a sports reporter in Melbourne.

Chisholm went on to be the press officer for the governor-general, the editor of Whos Who in Australia , and the editor-in-chief of the Australian Encyclopaedia . But it is for his nature writings, particularly about birds, that Alec Chisholms legacy endures. In almost 70 years of publication, he touched and inspired generations of Australians, sharing his boundless passion for birds. While his accounts may at times seem a trifle florid to the contemporary reader, they were a welcome relief to the stuffy formality and borderline pomposity of many ornithological writings of the day. One can see that, in his writing style, Chisholm was searching for a language as rich as the birdsong he so loved.

And the range of his references, typical of such a voracious autodidact, is both egalitarian and eclectic. Chisholm happily allows snippets from Wordsworth, Shakespeare, and Greek mythology to merge with observations taken from serious ornithological literature, quotes from local schoolchildren, and examples of Indigenous bird knowledge to instil in the reader the sense of wonder that Australian birds could evoke.

Eschewing the pomposity of scientific nomenclature, Chisholms style was direct and passionate, conveyed in a plain language that could be understood by all readers. The simple title, Mateship with Birds , speaks volumes unlike the overly descriptive titles given to most bird tomes of the era, this is unadorned and direct, focusing on the connection between people and birds through the concept of mateship with which Australians so often identify.

As an example of his popular touch, thornbills are referred to throughout this book as tit-warblers a name that Chisholm knew would register with the majority of his readers even though he sat on a committee that, given the job of codifying vernacular names for Australian birds, had designated the name thornbill for the indigenous family of small, insectivorous birds.

His commitment to the popularising of bird study did not always make him popular with the professional ornithologist set. The perceived stereotype of the birdwatcher is of a gentle soul, communing with nature. In the internecine world of birdwatching politics, however, nothing could be further from the truth. Chisholm was as willing a participant in a good stoush as any, being frequently described as querulous and quarrelsome. Others noted his feisty and obdurate nature, and he was certainly tenacious in his pursuit of what he felt was the correct course of action such as his vehement opposition to egg collecting and what he regarded as the unnecessary shooting of birds for scientific specimens.

Such clashes led to insinuations that Chisholm was pandering to populist sentiment, but what still comes through powerfully in his writing is that he was a bridge between the arcane academic world of ornithology and the general public. He seemed to innately understand that all the knowledge in the world is useless if cloistered among a select few.

Next page