Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Cal Cook, my partner,

Lily Cook, my heroine,

and

Pamela Marin, the gamer I admire most of all

A tanned, weathered hand lifts a VHS cassette. Clacks it into a videotape player.

Wheres the remote thingy?

A voice from the next room. Dad, are you watching it again?

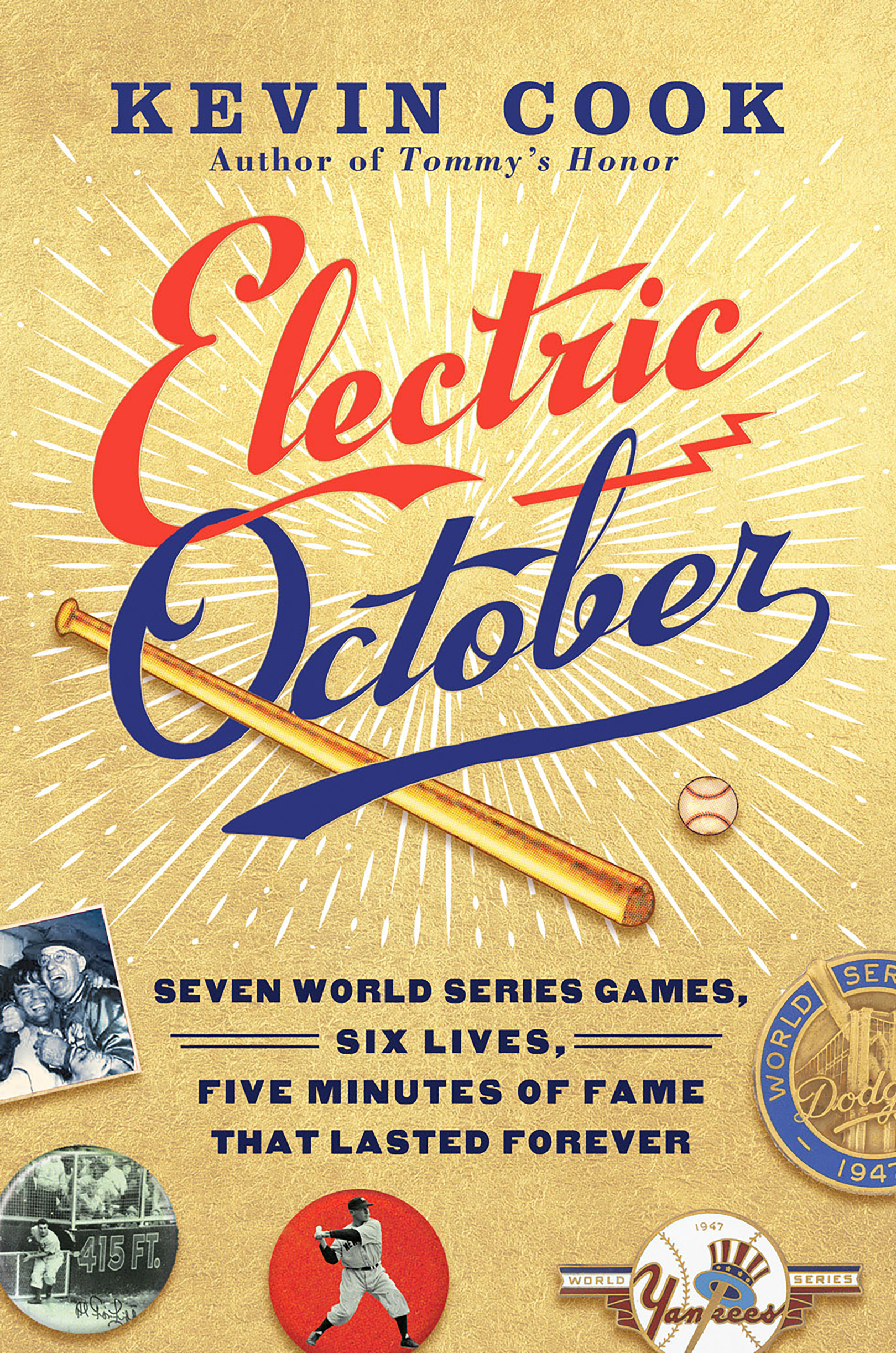

On the TV, Red Sox pitcher Bob Stanley peers in for a sign from Rich Gedman. Its October 25, 1986, Boston vs. the New York Mets in the most-watched World Series ever. Fifty million Americans see Mookie Wilson foul off Stanleys pitch. But in this little ranch house in the Bay Area, its not 1986 for long. The brightly colored TV screen blinks and reappears in black and white. Men in baggy flannel uniforms jog to their positions on a diamond that has bare spots in the grass. DiMaggio, Rizzuto, Berra. Its Game Four of the 1947 World Series, the New York Yankees against the Brooklyn Dodgers. The games most popular teams had both broken attendance records, the mighty Yanks at their gleaming stadium in the Bronx and the hope-springs-eternal Dodgers at Ebbets Field, their cracker box in Flatbush. Now they faced off in the first truly modern World Series.

It was the first integrated Series thanks to Jackie Robinson, who broke baseballs color line that year. It was the first televised World Series. But some things never change. Late in Game Four the Yankees, winners of ten World Series to Brooklyns total of none, are taking command. One more victory and theyll lead the 47 Series three games to one. And theyre practically rubbing the Dodgers noses in it. With two outs in the ninth inning Bill Bevens, the Yanks rangy fireballer, has thrown eight and two-thirds innings of no-hit ball. Hes one out from the first no-hitter in World Series history.

But Bevens is spent. He has thrown 135 pitches. His jersey soaked with sweat, he rears back and uncorks another fastball.

Pinch hitter Cookie Lavagetto swings through it. He shakes his head at himself. The pitch was high and away, right where he likes em, and he missed it.

Thirty-nine years later, watching the scratchy black-and-white screen, he calls to his son in the other room.

Want to watch?

Sure, why not?

Ernie Lavagetto joins his old man in front of the TV. They have seen this tape many times.

On the screen, Bevens winds up and fires, shutting his eyes as he lets the ball go.

Another fastball, Cookie says, watching his younger self lunge at the pitch.

You can hear his bat meet the pitch with a clack that sends the ball on a long arc toward the GEM RAZOR billboard on the right-field fence at Ebbets Field, toward baseball history and the rest of his life.

* * *

This is the story of half a dozen men who shared a week that changed their lives forever. The six of them played, practiced, traveled, fought, laughed, ate and drank, won and lost with a couple of immortals whose names are still celebrated seventy years later: Jackie Robinson and Joe DiMaggio. But Cookie Lavagetto, Al Gionfriddo, and manager Burt Shotton of the Brooklyn Dodgers, and Bill Bevens, Snuffy Stirnweiss, and manager Bucky Harris of the New York Yankees were baseball mortals. Theyre remembered by the games historians and trivia buffs if they are remembered at all. Small-town boys, most of them, each one a hometown hero, they spent a week in the national spotlight and then faded away, forgotten, until somebody mentioned the 1947 World Series.

The six of them played key roles in a World Series that Joe DiMaggio called the most exciting ever. Red Barber, the radio voice of the games golden age, swore hed never witnessed such unlikely highs and lows, a time when the stars became supporting players while journeymen, scrubs, and substitutes played hero. Or goat. Or both.

For some the 47 Series presaged happier times. For others it was the one shining moment in a losing battle to stay in the majors. Three of them were finished in the big leagues after 1947.

One spent the rest of his days living down a near miss in the game of his life.

Two spent decades shaking fans hands, accepting free drinks and pats on the back, telling and retelling the story of their long-ago heroics.

One died young in a disaster as bizarre as the 47 World Series.

Twothe managersendured endless what-ifs about the moves they made that fall in Brooklyn and the Bronx.

This is the story of how seven ballgames shaped the rest of their days. Its a true tale of fame, friendship, teamwork, memory, and lifes biggest challenge: how we deal with the cards that fate deals us.

As Barber put it, For human stories, youll never beat this one.

Burton Edwin Shotton was born in 1884. Professional baseball was only fifteen years old. Mark Twain, who finished writing The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn that year, described baseball as Americas very symbol of the drive, and push, and rush and struggle of the raging, tearing, booming nineteenth century! Like Huck Finn, young Burt imagined a wider world than the small-town Midwest of his youth. The son of a sailor who manned the freighters plying Lake Erie, he grew up in Bacons Corners, Ohio, just west of Cleveland. As a teenager, Burt loaded iron ore onto those freighters. On weekends he earned extra nickels as a substitute barber. Free hours he played sandlot ball. Most turn-of-the-century Americans were more like Theodore Rooseveltmore bullish on boxing and college footballbut dockworker Burt Shotton daydreamed about baseball, about slashing doubles and stealing bases like Jesse Burkett and Bobby Wallace of the major-league Cleveland Spiders.

Soon Burt was fighting his way up through baseballs bush leagues. Turns out he had speed to burn, enough speed to beat out infield singles and lead minor-league teams in stolen bases. He slowed down just long enough to marry a fan of one of those teams, the Steubenville (Ohio) Stubs. Mary Daly, a plump, bubbly brunette as old-fashioned as he, became Mrs. Burt Shotton in 1909. They would spend more than half a century together.

Burt made his big-league debut that season, then bounced back to the minors for a season before joining the St. Louis Browns to stay in 1911. That last-place Browns club was skippered by his old Spiders hero Bobby Wallace, a Hall of Fame player who proved to be a fretful washout as a manager, winning 57 games and losing 134 before he was replaced early in the 1912 season. Two years later, Browns owner Robert Lee Hedges hired another young manager, Branch Rickey. Shotton starred for Rickey, stealing more than forty bases four years in a row, with batting averages from .269 to .297. He played shallow in center, making shoe-top catches that turned bloops into outs, racing back to snag long fly balls. Like every speedster he got nicknamed Barney after Barney Oldfield, the first one-hundred-mile-an-hour race car driver. A 1915 poll of big-league players chose three All-Star outfielders: Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, and Burt Shotton.

Like most big-league stars, Shotton resisted overtures to jump to the upstart Federal League, which placed a team in St. Louis, the Terriers, to vie with the major-league Browns and Cardinals. But some players made the leap. Future Hall of Famers Chief Bender, Three-Finger Brown, and Bill McKechnie joined Federal League clubs. Aging shortstop Joe Tinker of Tinker to Evers to Chance fame jumped to the outlaw leagues Chicago Whales, whose owner built a new ballpark that would later become known as Wrigley Field. After the Federal League folded in 1915, the owners of the Baltimore Terrapins franchise brought an antitrust lawsuit against the National and American leagues. That suit went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that because baseball was a sport, not a business, it was immune to federal antitrust laws. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote that personal effort is not a subject of commerce. In effect, the court granted major-league owners monopoly power over their players, an ownership right that lasted until the players union finally beat them in court half a century later.