My

Avant-Garde

Education

A MEMOIR

Bernard Cooper

Contents

Sections of this book have previously appeared in the following publications:

Granta, Los Angeles Magazine, Graywolf Forum 2003, The Best American Essays of 2008 , and The Best American Essays of 1997

Blank Canvas The Mid-American Review and Harpers Magazine

Labyrinthine The Paris Review

The Insomniac Manifesto The Santa Monica Review

Uses of the Ghoulish Los Angeles Magazine

A Thousand Drops (adapted from Something from Nothing) New York Times Magazine

I am for an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum. I am for an art that grows up not knowing it is art at all....

CLAES OLDENBURG

Like art, sex... was a shudder of hypotheses, a debate between being and nonbeing, between affirmation and denial.

ANATOLE BROYARD

Art always changes. The avant-garde stays the same.

MAX STEELE

1. Teaching a Plant the Alphabet

The windowless room is dark except for static sputtering on a video monitor. Beside the monitor, on one of the institutes stackable chairs, sits Jim, a gaunt young man who stares at his knees and pounds them again and again with his fists. His assault is as unrelenting as the static. That must be the point , I think, but my conviction quickly fades. I shift in my seat and look around to see if anyone appears to understand whats happening. Postures of contemplation emerge from the gloom: chins propped on hands, jaws grinding gum. Several students lean forward, mesmerized by the granulated light and the steady thwacks of impact. Our instructor, the conceptual artist John Baldessari, stands in a corner. A bulky six-footer with shaggy white hair and beard, his expression is, as always, inscrutable, his hands buried in the pockets of his jeans. He knows that the aesthetic value of any object or activity can not be measured hastily; the history of the avant-garde is the history of critics who rushed to judgment, whom time proved foolish. Here at the California Institute of the Arts, one must inch toward, rather than jump to, conclusions.

Jim continues to pummel himself and no one speaks. Words would be brutish and premature. No snickering or glancing at ones watch. Even coughs and throat clearings are kept to a minimum. And so we stare in a kind of numb reverence until a secretary from Admissions barrels into the dark room to deliver a phone message. She squints against the gloom and plunks herself into a chair beside Jim, holding out a folded note. Your mother wants...

He shushes her, punishes his knees.

She straightens her skirt and waits a moment. Jim, she says, I havent got all day. You mother wants you to...

His fists stop midair and he looks up from his lap. Im doing a performance, he hisses. Just as the secretary turns and finally sees a roomful of students staring back at her, Jim lurches to his feet and hits the monitors Off switch. Static evaporates. Your mother, she continues in utter darkness, wants you to phone her after class.

Jim opens the door and stomps into the hall, the secretary hurrying behind him and wagging the message in her outstretched hand. Darkness again when the door slams shut. The rustlings and murmurs of my classmates. I begin to wonder if the secretarys intrusion was planned, like a certain performance in the Ice Capades that thrilled me as a child, the skaters phony falls and failing props eliciting gasps from the audience. Maybe Jims temperamental exit was part of his performance, a comment on the fragility of artists egos. I can hear the instructors huge hands patting the cinder-block wall, groping for the light switch. Outside, sunlight is shining on the freeways, gas stations, fast-food chains, and tract homes surrounding the campus; whether or not Jim finishes his piece, the world will plod on. I cant admit this to anyone (to do so would be considered retrograde and bourgeois) but I find myself longing for ordinary, unselfconscious actsscratching an itch, swatting a flyacts without the aftertaste of art.

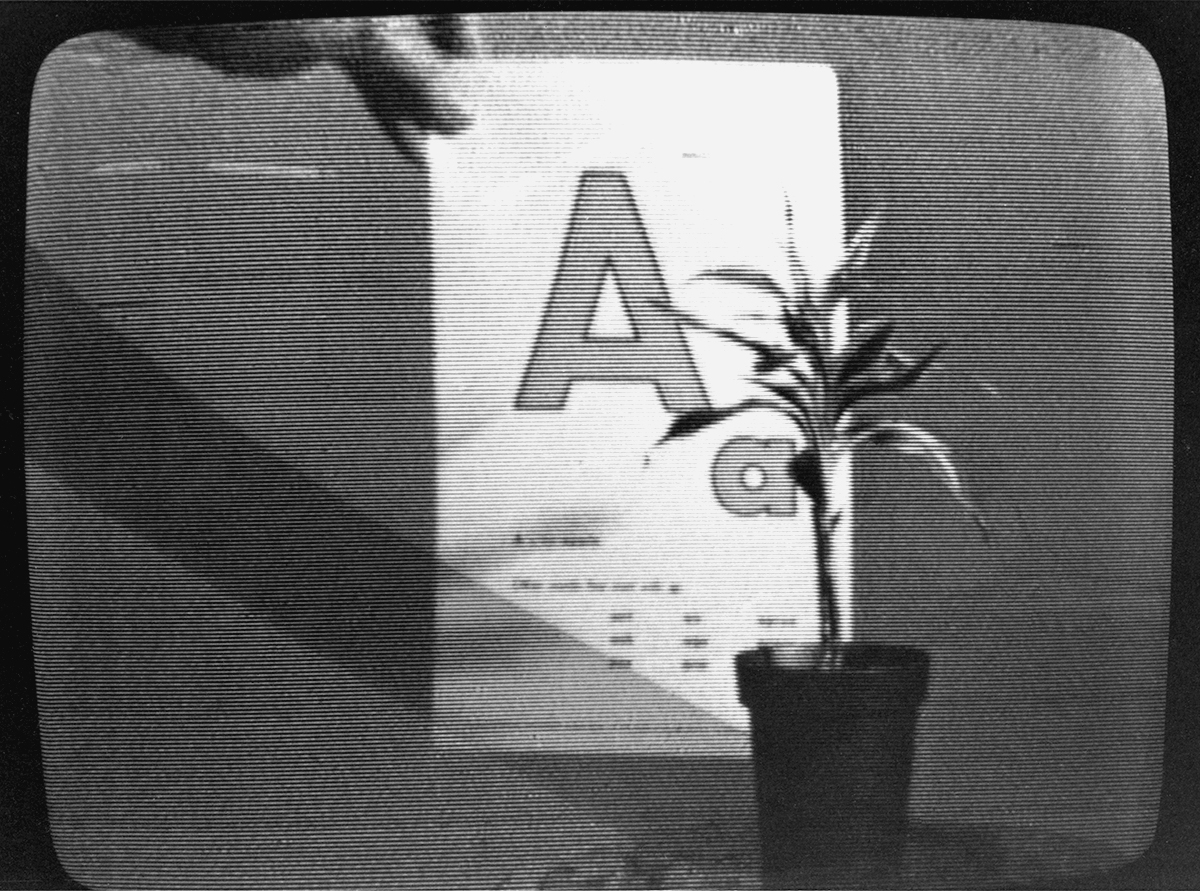

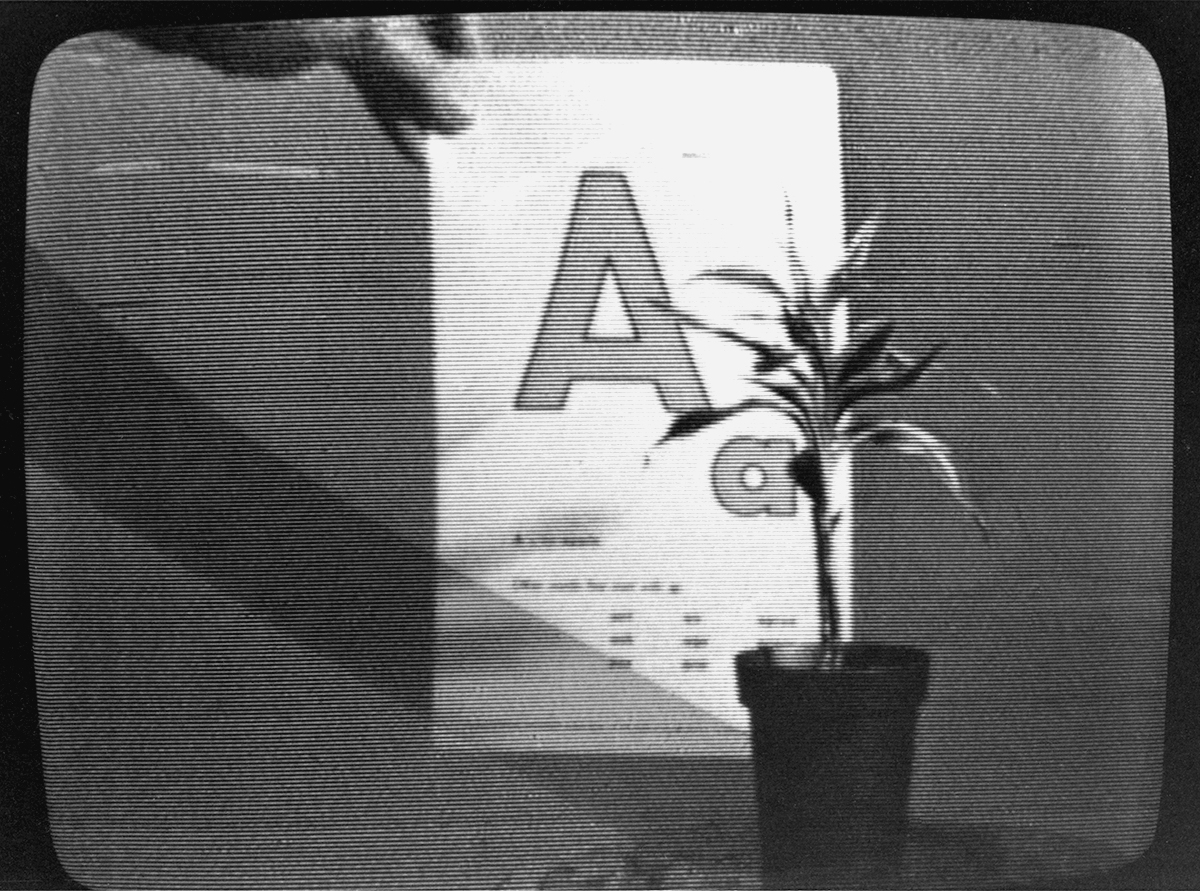

The room revives in a shuddering flood of fluorescent light. Mr. Baldessari considers what to do now that Jim has left in a huff. He touches a finger to his lips, thinking. The post-studio seminar is barely half over. Since the monitor is already here, he decides to show one of his own videos and mumbles something about how the piece, Teaching a Plant the Alphabet , caused quite a stir when it was shown at his gallery in Milan. He rummages through his dilapidated briefcase and slides a cassette into the console.

The cameras viewpoint is stationary and the performance, thanks to films like Andy Warhols eight-hour-long Sleep , unfolds in real time. And herein lies the phenomenon I remember most about graduate school: real time sagging in seminars, in the vast cafeteria, in the ultramodern library, and especially in the labyrinth of long white hallways as I searched among hundreds of identical rooms for classes in Earth-Works, The Happening, Movement as Anti-Dance, The Death of Painting in the Seventies, The End of Art.

If reticent in class, Mr. Baldessari is quite enthused in his video. He stands facing a small potted plant and holds up, one by one, twenty-six flashcards. The leaves are so pert they seem to pay attention. He croons, chants, sounds out each letter with loving persistence. At first, the futility is funnythat poor dumb flora! But I begin to lose interest at about F or G , and think how odd it was that the secretary had walked into a pitch-dark room where a young man, apparently alone, sat in a chair while beating his knees to the sound of static, the sight of which didnt alarm her in the least, didnt so much as give her pause. Had everyone at CalArts become so inured to the avant-garde that no behavior, regardless how bizarre, could shake our composure or quicken our pulse? Had the cutting edge grown dull at last? Did I have, or want, a future in the arts?

My awakening to the world of avant-garde art had taken place ten years earlier in my junior high school library. Diagonal shafts of light slanted through the Venetian blinds. Rotary fans turned overhead, stirring currents of warm air. Every now and then the librarian shushed talkative children as she silently rolled a cart through the stacks. These details come back readily because, in a lifetime of generally sluggish and imperceptible change, there followed a moment of such abrupt friction between who I was and who I would become, its a wonder I didnt erupt with sparks. Instead of looking up the major exports of Alaska for my geography report, I slouched in a chair and leafed through an issue of Life magazine. A boldface headline caught my attention: You Bought It, Now Live with It. The article profiled the handful of New York art collectors who were among the first to buy the work of Pop artists. Although Pop art was routinely savaged by critics for exalting the banalbillboards, supermarkets, Hollywood moviesthis new breed of collector didnt care.

All that other stuff, grumbled a collector named Leon Kraushar, referring to the sum total of art history before Pop, its old, its antique. Renoir? I hate him. Czanne? Bedroom pictures. Theyll never kill Pop, theyll just be caught with their pants down. They , Kraushar seemed to imply, were a bunch of stuffed shirts, scoffers and doubters, the self-appointed enemies of fun. Kraushar was shown in his Long Island house, lounging on the couch next to a stack of Andy Warhols Brillo boxes. Behind him stood a life-size plaster jazz trio by sculptor George Segal. The musicians held real instruments, their bodies frozen into a white glacier of improvisation.

Next page