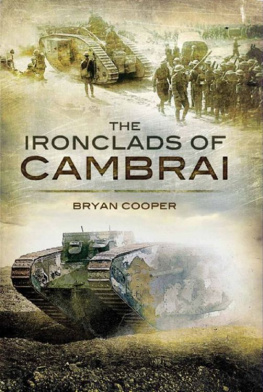

THE IRONCLADS

OF CAMBRAI

THE

IRONCLADS

OF CAMBRAI

by

BRYAN COOPER

Pen & Sword

MILITARY

First published in the United Kingdom as The Battle of Cambrai

in 1967 by Souvenir Press.

Reprinted in this format in 2010 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Bryan Cooper, 1967, 2010

ISBN 978 184884 176 5

The right of Bryan Cooper to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted

by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording

or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the

Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

by the MPG Books Group

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Wharncliffe Local History,

Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper,

Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Illustrations

ON the morning of November 21, 1917, the church bells of London rang out for the first time since the start of the Great War. They were celebrating a sudden and dramatic victory which had taken place the day before near the town of Cambrai, in northern France. For the first time since the two opposing armies had become deadlocked in the trenches of the Western Front, the mighty German defensive system of the Hindenburg Line had been broken. The Third Army of the British Expeditionary Force had advanced five miles along a six-mile front, and in a matter of hours had accomplished more than in any other single operation during all the months of fighting on the Somme and in Flanders.

It was a stirring victory, and gave the public at home their first chance of jubilation since the early days of the war. For by now, the initial flush of enthusiasm had waned. Young men no longer queued up in their thousands to volunteer for the Front. The eager, adventurous ones had gone anyway, most of them never to return, and conscription had now become necessary. No longer did elegant young ladies tour the streets of London, handing out white feathers to any men who were not in uniform. The flag waving and the jingoism had been replaced by a deep sense of depression. The heroic phrases did not seem to ring true against the rising tide of casualties, the lame and the blind, the shell-shocked and the gassed, who were straggling back from the Front. Food was becoming scarce as a result of German submarine activities. Bombing raids were becoming more frequent. Many people were, for the first time, beginning to ask themselves just what the war was all about.

The news was no less welcomed on the Western Front. The year had opened with a certain degree of hope and optimism, with Haig and his commanders confident that their tactics would win the day. It was ending as the worst year of all for the Allies. Men wondered if the war might go on forever. The Western Front had stagnated into the horror and futility of trench warfare in which no side was able to break the deadlock. Troops of the British, French and Commonwealth armies faced the Germans across a No Mans Land that was no more than a few yards wide in places. Each side had burrowed into the ground, and the two great defensive lines of barbed wire, trenches, dug-outs and machine-gun posts, stretched side by side in a wavering barrier right across Europe, from the Belgian coast to Switzerland. The Germans were particularly well entrenched. During 1916 and early the following year, while the two monolithic armies had been locked in fruitless combat, they had been hard at work behind their front lines, building one of the greatest defensive systems the world had ever seen. The Siegfried-Stellung, or the Hindenburg Line as it became generally known, extended some 45 miles from the British front near Arras, down past Cambrai and Saint Quentin, to a point six miles north-east of Soissons. It was more than four miles deep in places, and made up of three distinct lines of trenches, with fifty yards or more of barbed wire massed in front of each one. Concrete positions were built for machine-guns, and a network of railways constructed so that troops and supplies could be brought right up to the front. The Line had been chosen for its strategic position, rather than to retain the few miles of captured territory between it and the existing front lines. The Germans considered this massive barrier to be impenetrable, and so it was, apart from a partial breakthrough during the Arras campaign, until the Battle of Cambrai. Behind it, they planned to stand on the defensive, to enable divisions to be sent away to other fronts and to be a position of rest and recuperation for troops who had been fighting in Flanders. Also, it gave them time for their submarines to continue the destructive work against British shipping.

When in March, 1917, the Germans had fallen back to the Hindenburg Line, they left behind an area of utter devastation. Everything had been destroyedtowns, villages, even trees. In their place were planted mines and booby-traps. Slowly, the Allied forces made their way forward to reestablish contact with the enemy. And then had begun the furious assaults to try and flank the Line, the British in Flanders and the French further south around Saint Quentin. Men were hurled in their tens of thousands against well-defended positions, only to be mowed down by fire from machine-guns which some British generals had previously considered overrated weapons. The casualties mounted to terrifying proportions, of a kind never before, or since for that matter, experienced in war. Often, men were expended for no other hope of success than that of wearing down the enemys reserves, the fatal policy of attrition ordered by generals who rarely, if ever, left the safety of their rearward headquarters to see for themselves the hell of the front line. They might have learned a lesson from the five months of fruitless fighting on the Somme the previous year, when the British lost 420,000 casualties60,000 on the first day aloneand the French nearly 200,000. But nothe same kind of campaign had to go on. The battles followed the same patterndays or weeks of artillery bombardment, and then a blind rush forward into a curtain of machine-gun fire. The bombardment seemed to be the only apparent way of destroying the barriers of barbed wire and giving the infantry even half a chance. It certainly enabled the enemys front lines to be taken during the initial attack, which was why, by 1917, both sides had learned to keep their forward positions only lightly held, with the real defence in depth at the rear. But it also gave ample warning of a coming attack. Every time the British and French made such an attempt, the Germans knew what was coming and had time to bring up reserves to strengthen their defences.

And so the slaughter continued. During the Third Battle of Ypres in the summer of 1917, the British casualties over three months were nearly 400,000for the gain of no more than a few miles of cratered mud-flat and the ruins of a village that was called Passchendaele. The Hindenburg Line remained unbroken and unflanked.