Contents

Landmarks

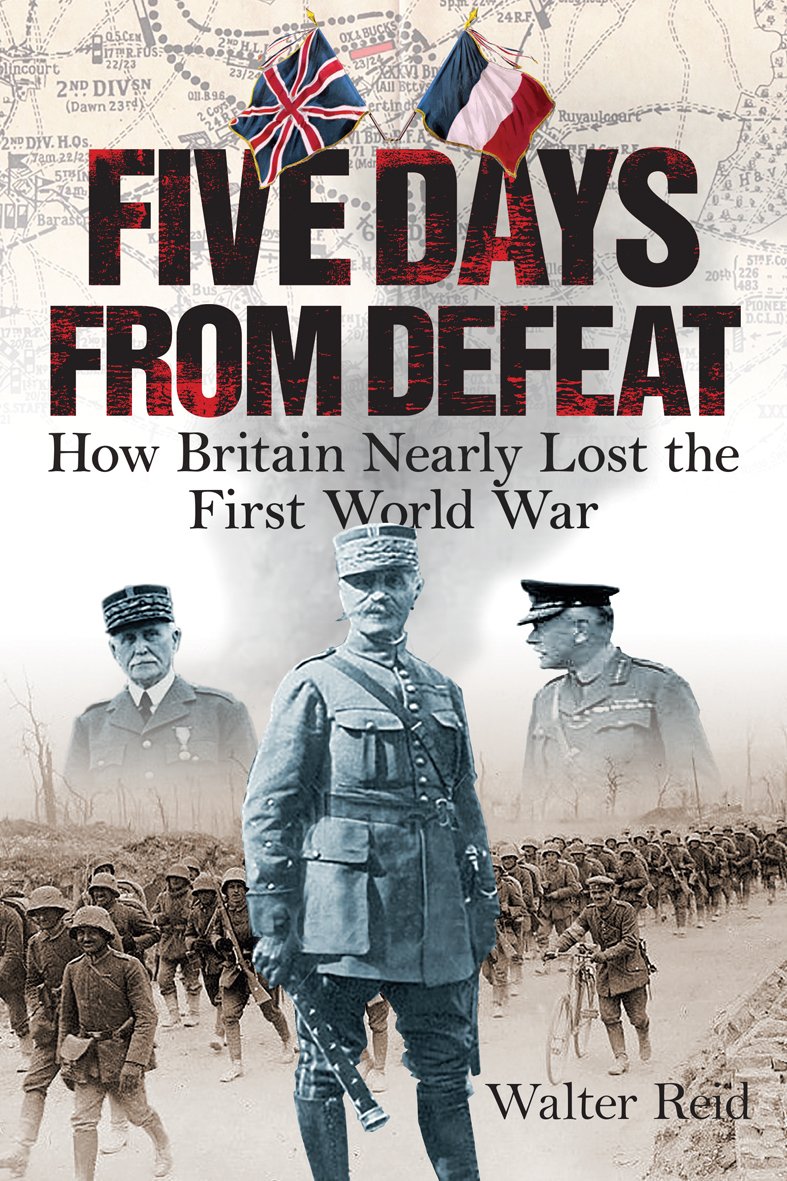

Other books by Walter Reid

Arras 1917: The Journey to Railway Triangle

Architect of Victory: Douglas Haig

Churchill 194045: Under Friendly Fire

Empire of Sand: How Britain Made the Middle East

Keeping the Jewel in the Crown: The British Betrayal of India

Supreme Sacrifice: A Small Village and the Great War

(with Gordon Masterton and Paul Birch)

First published in 2017 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Walter Reid 2017

The moral right of Walter Reid to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 0 85790 941 1

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Biblichor Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Gutenberg Press, Malta

To the precious, vivid and ever-present memory of Flora

I suppose history never lies, does it? said Mr Dick, with a gleam of hope.

Oh dear, no, sir! I replied, most decisively. I was ingenuous and young, and I thought so.

Charles Dickens, David Copperfield

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

I owe a huge debt of gratitude to my dear friend John Hussey, OBE. Amongst many other things, John has written some outstanding articles on aspects of the First World War. They glitter and scintillate in the pages of many scholarly journals and illuminate this passage of history. In the course of researching them he amassed a considerable volume of fascinating material on the period which this book covers, and this treasure-store with immense generosity he handed to me.

His generosity was three-fold, perhaps greater. For one historian to make the fruits of his research available to another is a rare and kind act. To hand it to someone who might well place quite different interpretations on the material is even more generous: John is certainly not to be taken to be agreeing with my conclusions he has his own views which can be strong and are based on rigorous logic but he did not seek to influence my own analysis. Finally, he read this book in draft when he was very much involved in the final stages of work on his magisterial two-volume history of 1815 and the conclusion of the Napoleonic adventure, Waterloo: The Campaign of 1815, which will stand as a definitive account for many years.

I acknowledge with thanks permission from the Earl Haig and the Trustees of the National Library of Scotland to quote from the Haig Papers, of which they are respectively copyright owner and material owners; and from the Trustees of the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives, Kings College, London, to quote from the Robertson and Kiggell Papers.

I have had the good fortune to have had two wonderful assistants who helped the book along its way, checking, researching and imposing order on my wayward working practices. Dawn Broadley took the first watch, and Gwen McKerrell the second. I am immensely grateful to both. They had much to put up with, but never said so.

As always, Hugh Andrew and Andrew Simmons, respectively Managing Director and Editorial Director at Birlinn, were wonderfully supportive and enthusiastic. It is always a great pleasure to work with them. Patricia Marshall was an outstanding copy editor, knowing apparently intuitively exactly when I was skating on thin ice, and humanely getting me off it.

Finally I record my gratitude to my wife, Janet, my gentlest and best critic, for all the fun and surprises of fifty years companionship, and for her support at a time when I was the least of those who needed it.

Beauly, Renfrewshire

August 2017

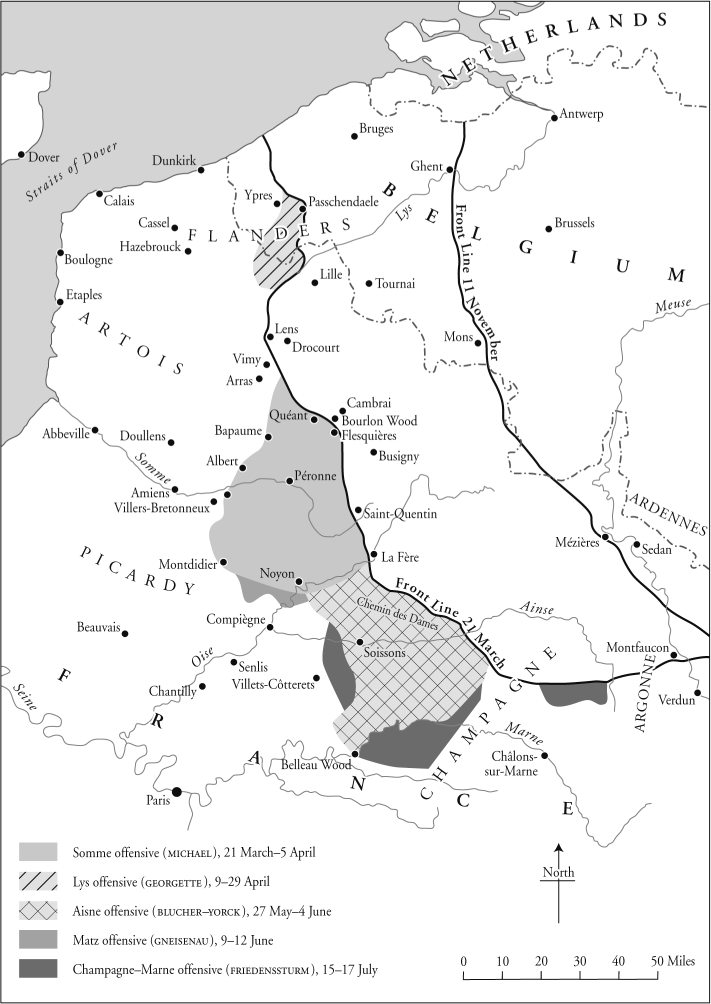

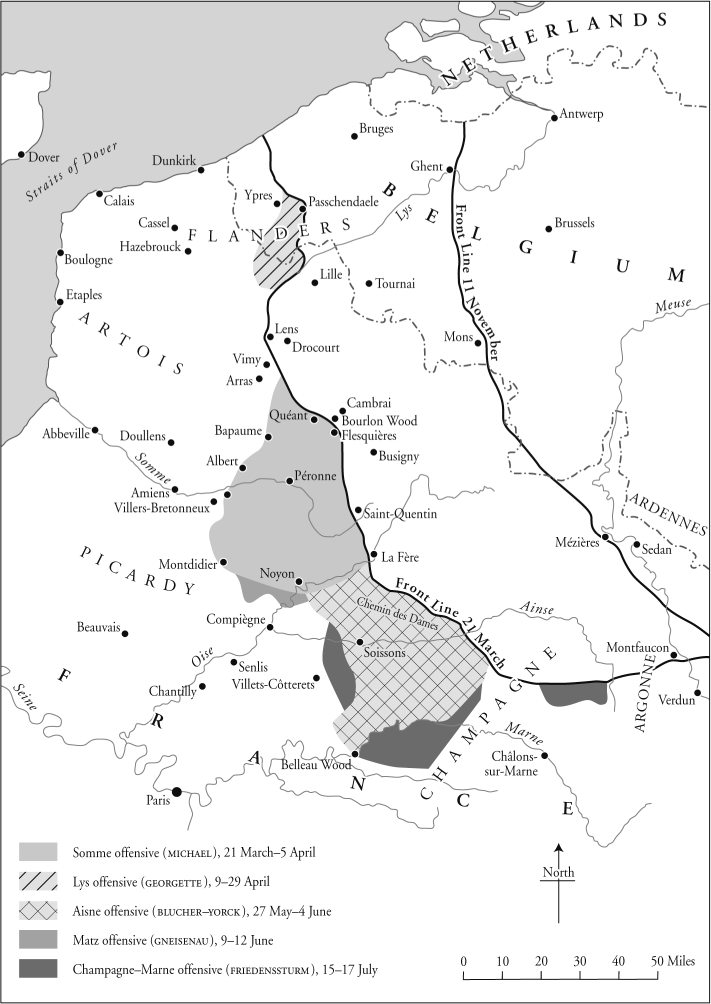

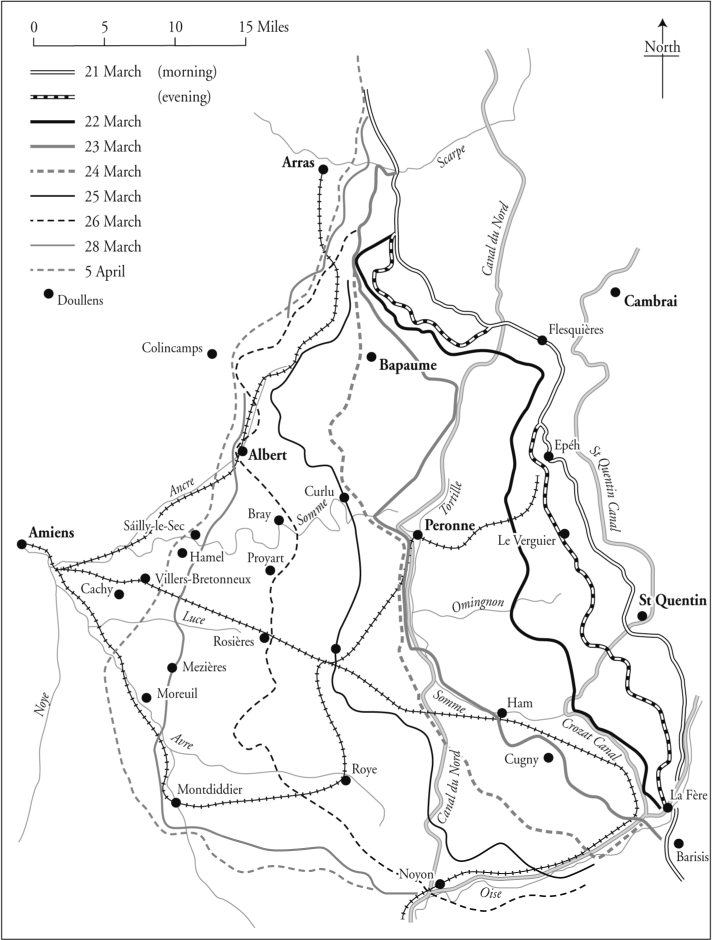

Ludendorffs 1918 Spring Offensive

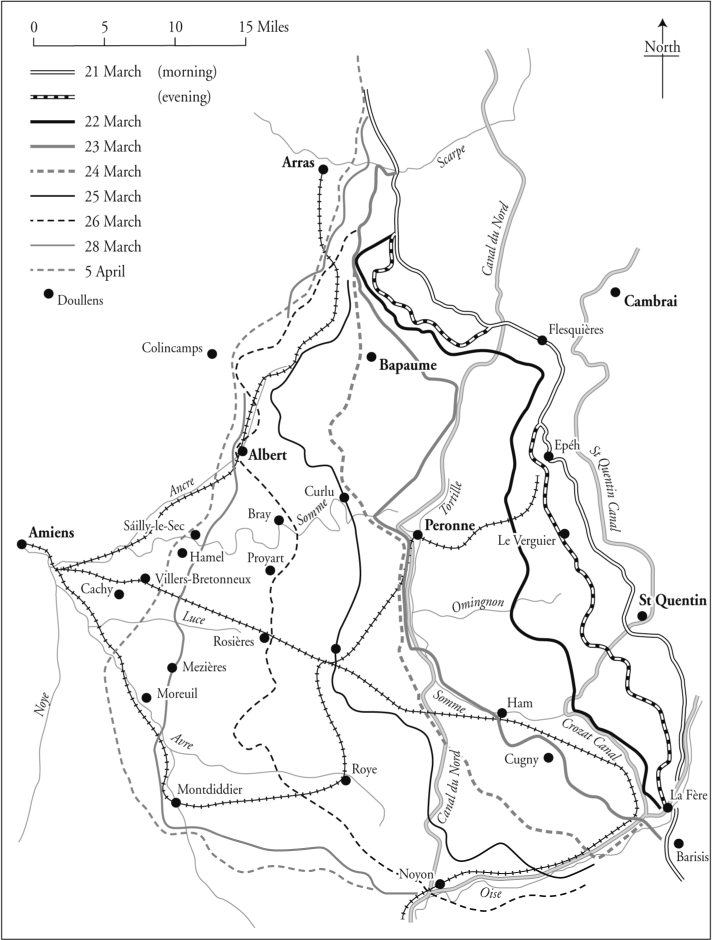

Movement of the Front, 21 March5 April 1918

Prologue

FIVE DAYS IN MARCH 1918 TOO GRIM TO BE REMEMBERED

21 March

The German army launched a massive attack on the British part of the Western Front. Aware that they might win the war now before the Americans were present in force and also aware that, if they did not do so, they would assuredly lose, the onslaught had all the berserk drive of what the Romans called Furor Teutonicus when they tried to describe the whirlwind attacks of the Germanic tribes in all their wrath. The assault was long prepared but had been well concealed. Ludendorff, the German commander, deployed tactics he had developed in Russia, essentially the storm-troop tactics that Hitler would use in 1940. His aim, like Hitlers, was to break the Allies by forcing Britain back to the Channel ports.

A devastating German artillery barrage opened at 04.40. By the time the infantry moved off, just five hours later, 3.2 million shells had landed on pre-registered positions. By the end of the day, Britain had suffered 38,512 casualties and lost 500 guns. The Cabinet secretary said that the day was one of the most decisive moments in the worlds history.

22 March

Heavy fog continued to assist the advancing Germans. Fifth Army, defending the southern part of the British line, was penetrated as far as its reserve line. French troops moved in to bolster the dazed British. The fighting was fierce but the Germans, looking at the extent of their gains, said that the British must have run like rabbits.

23 March

By now the Germans had advanced 22 kilometres in an 80-kilometre breach in the British line. The British Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig, requested very substantial aid from his French allies. British Fifth Army, falling back in confusion through inadequate defences, was disintegrating. It was put under French control. France complained that Haig was breaking contact, doing nothing for France except fleeing from her.

Haig feared that, if contact was lost, the British armies would be rounded up and driven into the sea. He began to talk of falling back to cover the Channel ports. There were fears in London that the government might fall. The Cabinet began to panic and contemplate evacuation. The Cabinet Secretary feared not only defeat in France but invasion of Britain.

24 March

Now Third Army, to the north of Fifth Army, was in retreat too. Fifth Army had fallen back a further eight kilometres and battlefield command had broken down. The Great Retreat of 1918, pretty much a rout, had begun. The Cabinet Secretary said that things were about as bad as they could be. In Paris, the president was adamant that contact must be maintained. Haig and his opposite number, Ptain, met late at night at Haigs forward HQ to try to coordinate plans. Little emerged from the meeting. Ptain was afraid that Haig was going to break away and head for the coast. Later, Haig was to allege that Ptain had ordered his troops to pull away to defend Paris.