Empire of Sand

Empire of Sand

How Britain Made the Middle East

WALTER REID

First published in 2011 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Walter Reid 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

The moral right of Walter Reid to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

ISBN: 978 1 84341 053 9

eBook ISBN: 978 0 85790 080 7

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Hewer Text (UK) Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound in the UK by MPG

For Dan, David, Frances, John and Judith, all regarded as members of my family which some of them are.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

When I was an undergraduate at Jesus College, Oxford, I lived for a year in what had been T.E. Lawrences rooms. They contained a portrait which his mother had given to the College. For that year the first face I saw every morning, after my own in the shaving mirror, was his. I cant say that the experience left me with a burning interest either in him or in the Middle East, but in the course of my years at Jesus I did make some friendships that have lasted almost half a century and none has been more special than that with John and Frances Walsh, who are among those to whom this book is dedicated.

Dr Patricia Clavin, one of Johns successors as History Fellow at Jesus, was kind enough to read the book in draft, as did Avi Shlaim, Professor of International Relations at Oxford. I am very grateful indeed to both of them for the time they took and for the comments and suggestions they made. The book is very much the better for them. I have also to thank Professor Niall Ferguson for finding time to help in the midst of all his activities on both sides of the Atlantic.

I am indebted to Professor Susan Pedersen of Columbia University for her assistance, which included making available to me a copy of her essay, The Meaning of the Mandate System: An Argument. Similarly, I am very grateful to Dr Penny Sinanoglou of Harvard University for supplying me with a copy of a fascinating paper, Half a Loaf? Re-evaluating the Peel Commissions Enquiry and Partition Proposal, 19361938. I must record my gratitude to Dr Simon Anglim of the University of Reading for his help in connection with Wingate, particularly his kindness in allowing me to read in draft the chapter on Wingate in Palestine from his now published book, Orde Wingate and the British Army, 19221944.

My interest in the subject-matter of this book was kindled in the course of long, passionate and hugely enjoyable discussions with Zara and Luway Dhiya and they accordingly have much to answer for. My thanks to them for their friendship. Thanks also Marc Accensi for alerting me to the textual significance of Tintin and the Land of Black Gold, originally Tintin au Pays de lOr Noir, and to Peter Martin for suggesting that a bulge in the frontiers of Transjordan (Winstons hiccup) was caused by a post-prandial incident at the Cairo Conference.

Im glad have the opportunity to acknowledge the help of Mteer Salem Albluyee, Christopher Khalaf, Sharif Masooh, Omar Namruga, Hasan Al Sabateen and Uri Simcha. The staff of the National Library of Scotland, particularly Elaine Simpson, were very helpful, as were the staff of Glasgow University Library. Thanks, once again, to Liz Bowers at the Imperial War Museum and also the team at its Photograph Archive.

Doris Nisbet came to work with me for two weeks in 1976 and stayed for 35 years. Id like to think that her stay was due to my relaxed and easy-going style, but the general view seems to be that it has more to do with her patience and forbearance. Thanks, anyway, for secretarial back-up and friendship over these years.

I was fortunate that at Birlinn Hugh Andrew has a special interest in the subject of this book, and was able to suggest important lines of enquiry. As always, it was fun to be working with Andrew Simmons, and Dr Lawrence Osborn is so much more than a superb copy-editor.

My familys interest in the book has been a support and stimulus. My daughter, Bryony, read the book in draft, and her input in terms of the structure of the argument and in other respects was invaluable. Janet read the draft more often, I imagine, than she would have wanted. But her comments, from a background of journalism, were essential. While the book was being written we celebrated our fortieth wedding anniversary. Neither writing the book nor anything else I have done in the course of these last forty years would have remotely been as much fun if it hadnt been based on a very special partnership.

Beauly, Bridge of Weir, August 2011

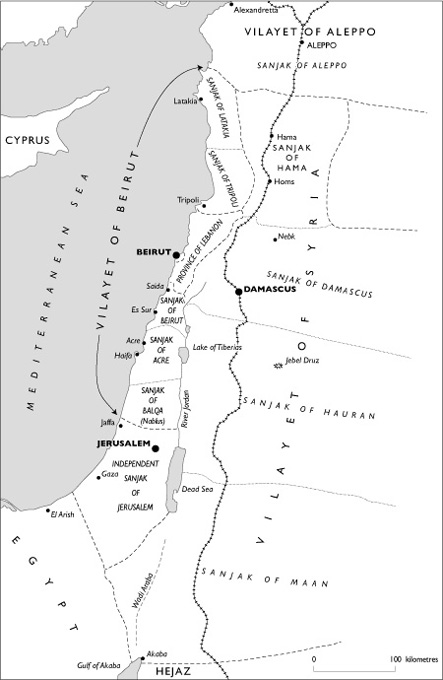

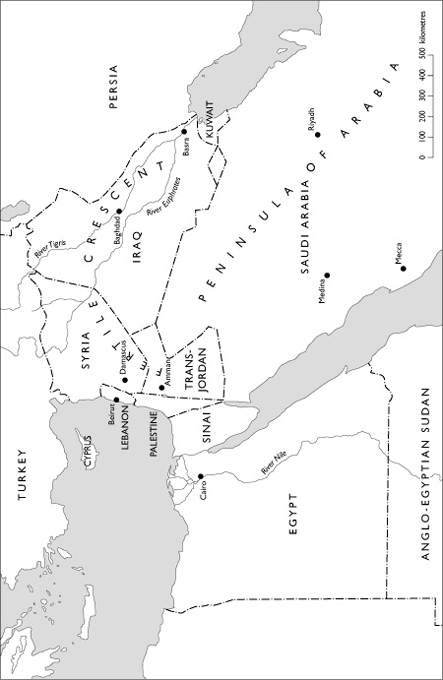

1. The Ottoman Middle East and its administrative units.

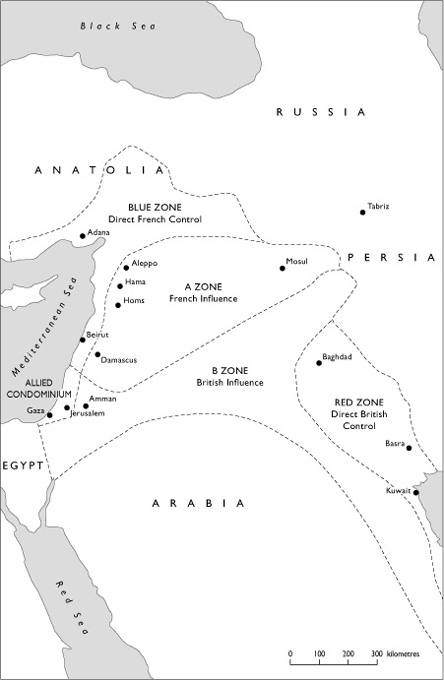

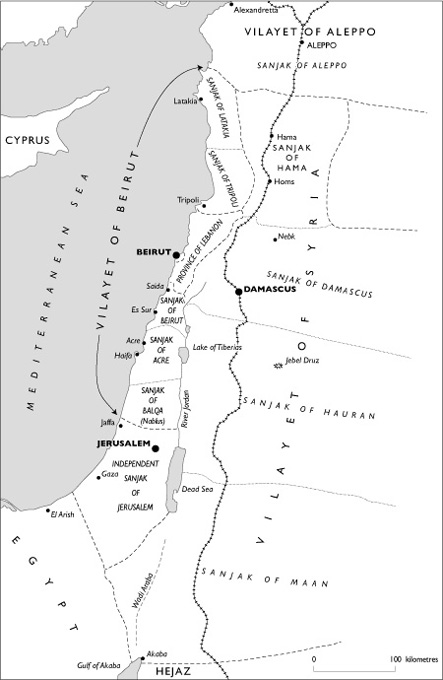

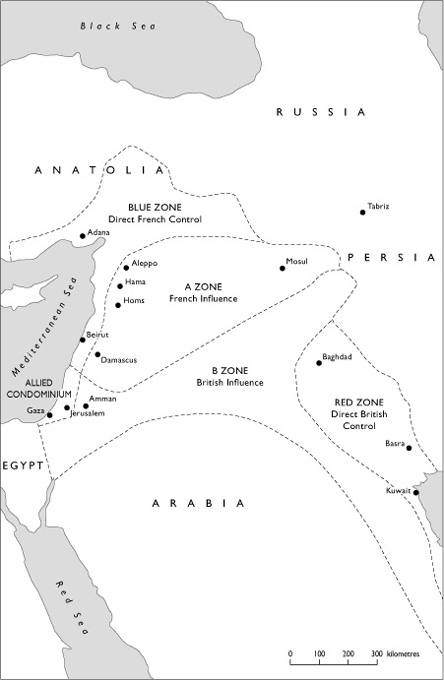

2. The Sykes Picot Proposal.

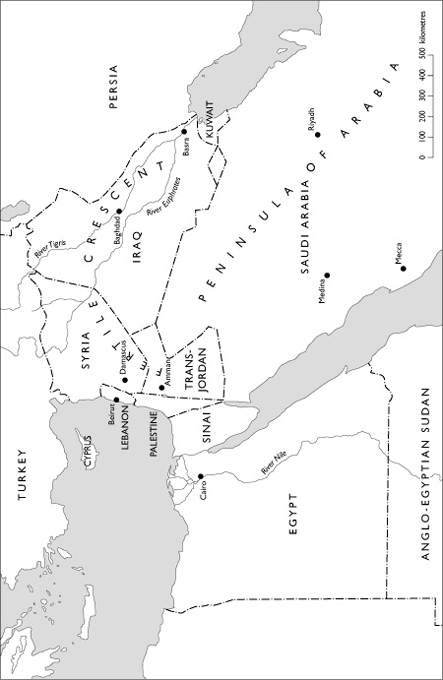

3. The Mandates.

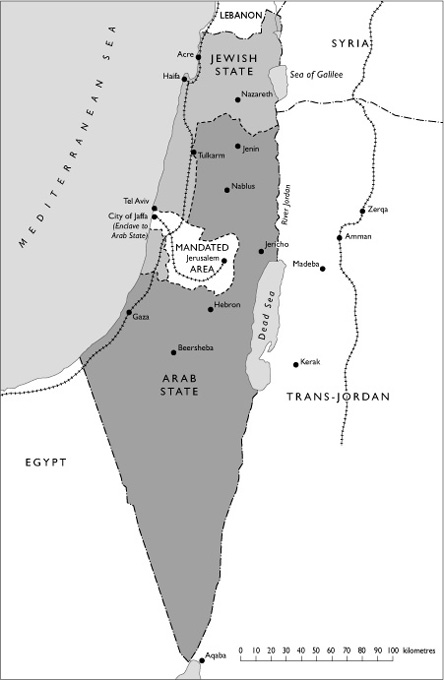

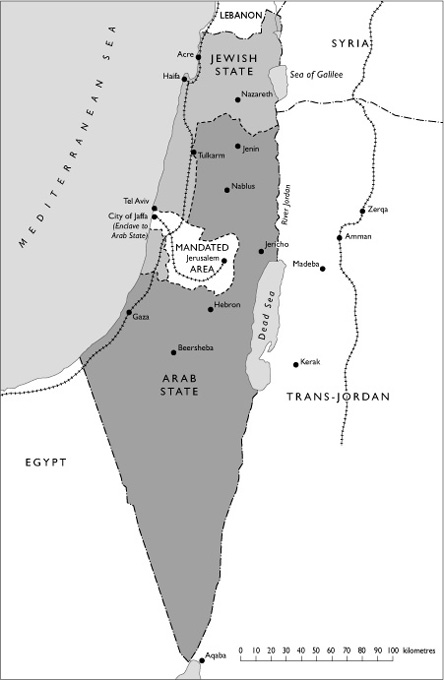

4. The Peel Commission Partition Plan A, 1937.

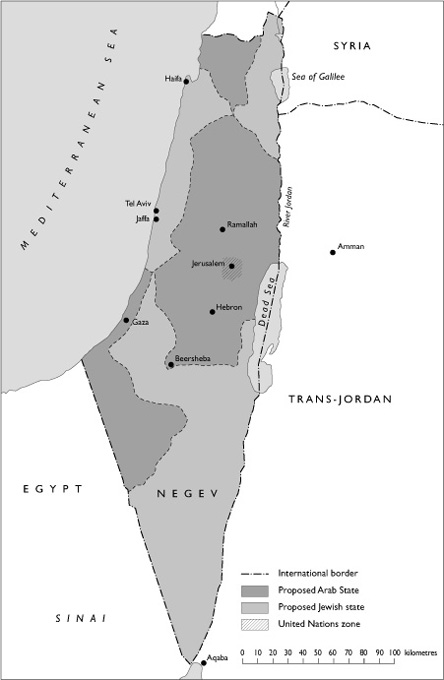

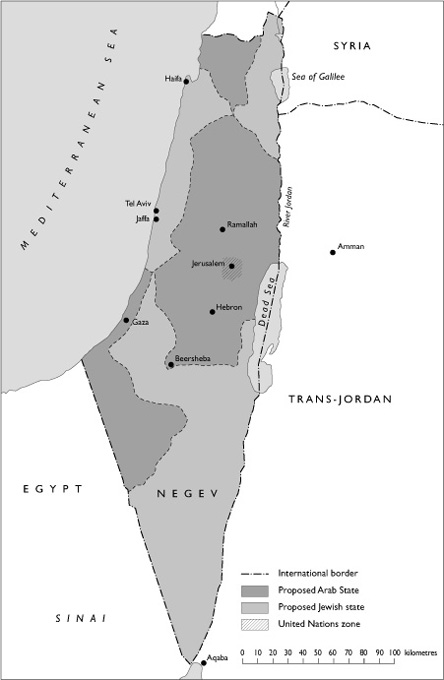

5. The United Nations Partition Plan, 1947.

I

BACKGROUND

1

INTRODUCTORY

Surveying the extent of the British Empire in 1883, Sir John Seeley, the Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge, said, We seem, as it were, to have conquered and peopled half the world in a fit of absence of mind. The lecture in which he made the remark was published and remained in print until 1956, the year of the Suez expedition. His line has been remembered, but is often misunderstood. He was not being whimsical, nor did he admire the amateurish spirit in which the globe had been painted red. He was deprecating the lack of serious planning behind an enterprise that had so much potential.

The Empire he was looking at was the Second British Empire, the empire that Britain built up after the loss of the American colonies. Contemporary documentary evidence shows clearly that Seeleys epigram was unfounded on fact. Even before Yorktown a great deal of detailed thought was being given to extending Britains overseas territories for strategic and mercantile reasons. A fit of absence of mind is not an appropriate expression in relation to that carefully planned exercise.

It is a much more appropriate description of the way in which the Third British Empire, the Empire in the Middle East, was acquired. The repercussions of that acquisition still reverberate. The reasons for it, largely unexplained, are fascinating.

The scale of this forgotten Empire was enormous. Between 1914 and 1919 the superficial area of the Empire expanded by roughly 9 per cent and in the 21 years from 1901 its population increased by some 14.5 per cent. By 1922 the Empire comprised 58 countries covering 14 million square miles, with a population of 458 million people. The extent of the Empire was seven times that of the Roman Empire at its greatest span. George V ruled over a quarter of the land surface of the planet, and his navies controlled effectively all its water surface. No wonder he collected postage stamps. His empire contained a quarter of the population of the earth.