Contents

Guide

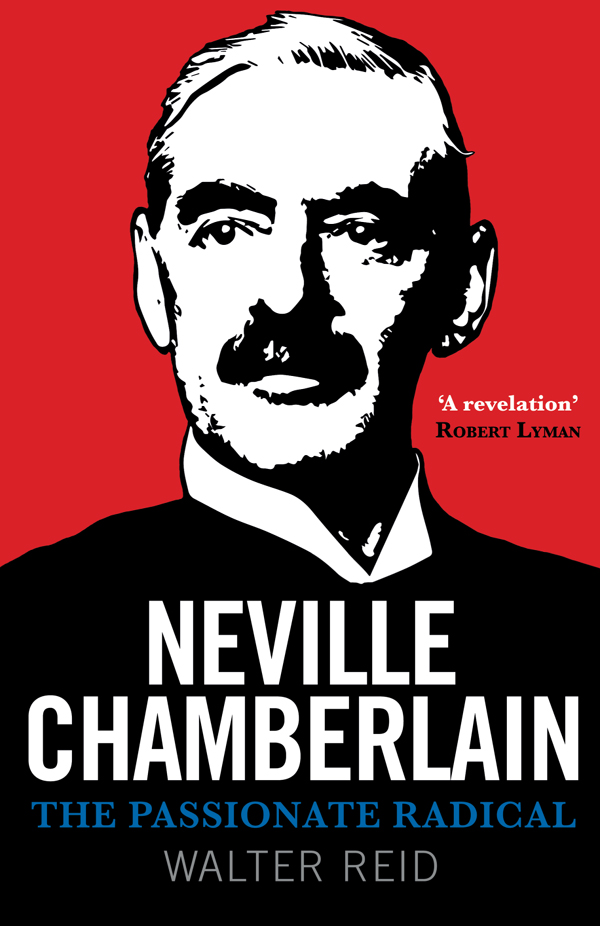

Neville Chamberlain

The Passionate Radical

For Lachlan

First published in 2021 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Walter Reid 2021

All rights reserved

The moral right of Walter Reid to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

ISBN 978 1 78885 482 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Contents

Prologue

A Puzzle

As the nineteenth century moved into the twentieth, a young man, subsequently to be a Prime Minister of Great Britain, lived rough for five years, a pioneer on the edge of the Empire. He rarely saw another European face. He spent long days labouring under the tropical sun. He tested his strength against that of the native labourers, who idolised him, and taught himself to sail single-handed. Who was he?

Some hints. He never went to university. He spent his frontiersman evenings educating himself, reading widely, coming to love Shakespeare more than any other politician of his time. Despite the rigours of this early life he was a man who enjoyed his pleasures. He was far from teetotal and would suffer from gout. He loved his cigars as well as his wine. He entered politics overshadowed by the reputation of a great parliamentary father, whose last days had been marred by cruel incapacity. He venerated his fathers memory and, an emotional man, his voice shook when he spoke of him. Could this be Churchill?

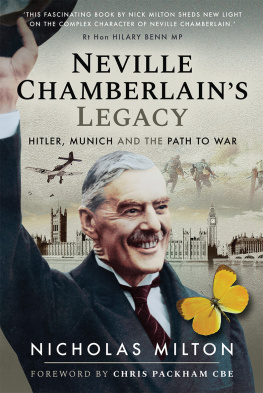

Given the title and subject of this book, this tease was never going to work; but in other circumstances it might have taken some time before the penny dropped and the hardbitten colonial pioneer was identified as Neville Chamberlain, the funny man with an umbrella who capitulated to Hitler and came back from Munich flapping a piece of paper and talking about peace in our time: the point I want to make right at the outset is just how misleadingly history remembers Neville Chamberlain.

The crass caricature has persisted. How can it be reconciled with the kind of young man who lived the life Ive just described? Thats what this book is about: unpacking a very private man and showing how very far his reality was from the way in which he is remembered: the undertaker, the coroner, the man with the umbrella.

What emerges is just how human and susceptible how passionate he was. It was to some extent his very humanity and vulnerability thats to blame for the bloodless image. In his shyness he constructed a shell to conceal what he thought demeaning. The fact that he was a man of flesh and blood does not of course mean that he was wholly likeable. He was far from that, very far indeed. He didnt feel it necessary to fight against his shyness. Indeed he was rather proud of his reserve, and behind it, like not a few shy people, he had a good opinion of his own abilities. Thus he could be high-handed and dismissive of those he felt to be his intellectual inferiors. Perhaps he should have resolved to master that shyness. Maybe not doing so was a kind of arrogance. Certainly, in the last half of his adult life, arrogance was his dominant characteristic.

But its worth understanding what made him tick, because hes much more complicated and interesting than the moustache and umbrella matchstick man. After his return from the tropics he was a businessman and a very good accountant (which doesnt help the image), but what truly animated him were not the intricacies of finance, but emotions and ideals emotions and ideals for which he worked through the medium of politics.

Not many 1930s politicians have images so fixed in the popular imagination as Chamberlain. Even people who have little interest in the politics of the interwar years will have, many of them, an image of this fussy little man (actually he was quite tall), almost a Charlie Chaplin lookalike, with his wing collar, an irritating moustache and an unbelievable capacity for credulity as far as Hitler was concerned. In the popular view, he was a tiresome presence which had to be disposed of before Churchill could get on with winning the war and bringing out the greatness of Great Britain.

The irony is that not only is the caricature so well defined, but also that its so wrong. The first paragraph of this section was a puzzle which didnt come off very well: Who was this man? The rest of the book is an attempt to answer the bigger and more difficult question: Who was the real Neville Chamberlain?, and well start by returning to a minor island in the Bahamas.

Chapter 1

Andros

Our first meeting with Arthur Neville Chamberlain is not with a foolish-looking elderly gentleman clutching a piece of paper at Heston aerodrome, but with a bronzed hunk, his shirt open to the waist, splashing through the Caribbean on the beach of the island of Andros.

He was a good-looking young man. At home, in a suit, he looked not unlike a youthful Anthony Eden. Here, in tropical gear, on the edge of the Empire, he looked more like Errol Flynn, or Douglas Fairbanks, or even Daniel Craig. His moustache was perhaps a bit on the bushy side (ahead of his marriage, years later, his wife advised him to trim it), but it was far from a walrus.

It was indeed a swashbuckling existence which young Neville led. Just a year earlier, when the enterprise was in preparation and his father has told him to sail from England to the Bahamas, Neville had said, The idea of travelling across the Atlantic all by myself was appalling, but I never thought of hesitating to obey, and he adapted immediately to the lifestyle of this frontier existence on islands which had been the home of the pirates Captain Kidd and Blackbeard.

It was a truly rugged existence. At first he lived in the simple home of a local resident, and one day he got by on two biscuits for breakfast and nothing else for the rest of the day.the mosquitoes got through his net and there was little sleep. The following night he slept on the ground, on pinecones. The mosquitoes were not so numerous as the night before but bad enough to worry.

Why was he here? As with almost all he did in his life indeed with everything that mattered he did it because of his father, Joseph Chamberlain, who was not only arguably the most influential politician of his age, but also a phenomenally successful businessman. But by the time that Neville was sent out to Andros in the Bahamas, Joe was getting short of money. Short in a relative sense. He still maintained an immense establishment at Highbury in Birmingham together with a substantial house in London, but the expectation, when he had sold off his business interests, that he could live on the income from his capital had proved to be over-optimistic. He had not received a ministerial salary since 1886, and although he was a Member of Parliament, parliamentarians in those days were unpaid. Furthermore, his investments had declined in value.