PREFACE

NEVER AGAIN!

The desire to avoid a second world war was perhaps the most understandable and universal wish in history. More than 16.5 million people died during the First World War. The British lost 723,000; the French 1.7 million; the Russians 1.8 million; the British Empire 230,000; the Germans over 2 million. Twenty thousand British soldiers died on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, while the ossuary at Douaumont contains the bones of some 130,000 French and German soldiersa mere sixth of those killed during the 302-day Battle of Verdun. Among the survivors there was scarcely a soul that was not affected. Almost everyone had a father, husband, son, brother, cousin, fianc, or friend killed or maimed. When it was over, not even the victors could feel victorious. The Cenotaph, unveiled on Whitehall on June 19, 1919, was no Arc de Triomphe but a symbol of loss. Every Armistice Day, thousands of Britons shuffled past it in mournful silence, while, on both sides of the Channel, schools, villages, towns, and railway stations commemorated friends and colleagues with their own memorials. In the years that followed the mantra was as consistent as it was determined: Never again!

But it did happen again. Despite the best of intentions and efforts aimed at both conciliation and deterrence, the British and French found themselves at war with the same adversary a mere twenty-one years after the war to end all wars. The purpose of this book is to contribute to our understanding of how this happened.

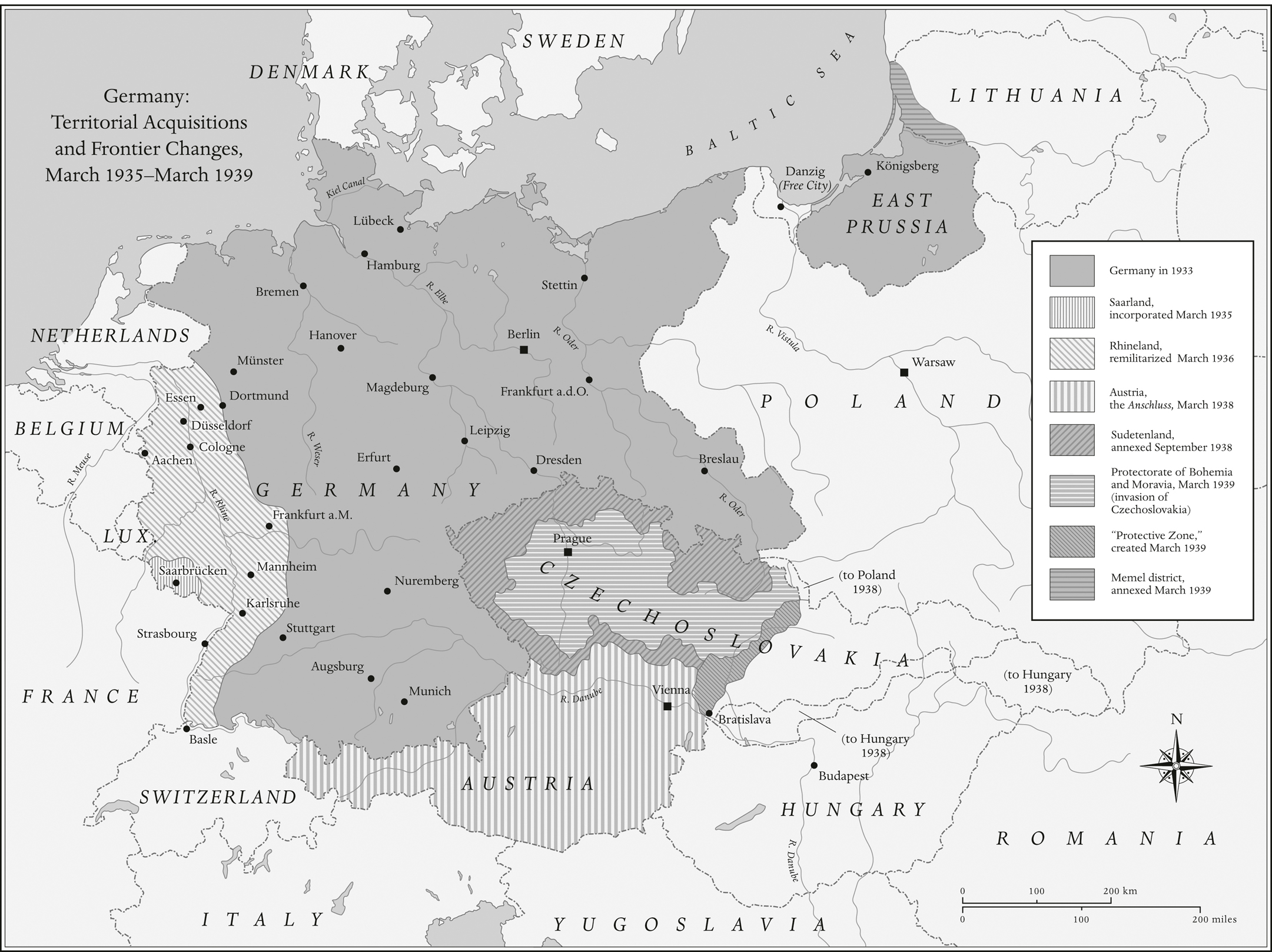

The debate over appeasementthe attempt by Britain and France to avoid war by making reasonable concessions to German and Italian grievances during the 1930sis as enduring as it is contentious. Condemned, on the one hand, as a moral and material disaster, responsible for the deadliest conflict in history, it has also been described as a noble idea, rooted in Christianity, courage and common-sense. Between these two polarities lies a mass of nuance, sub-arguments, and historical skirmishes. History is rarely clear-cut, and yet the so-called lessons of the period have been invoked by politicians and pundits, particularly in Britain and the United States, to justify a range of foreign interventionsin Korea, Suez, Cuba, Vietnam, the Falklands, Kosovo, and Iraq (twice)while, conversely, any attempt to reach an accord with a former antagonist is invariably compared with the infamous 1938 Munich Agreement. When I began researching this book, in the spring of 2016, the specter of Neville Chamberlain was being invoked by American conservatives as part of their campaign against President Obamas nuclear deal with Iran, while today the concept of appeasement is gaining new currency as the West struggles to respond to Russian revanchism and aggression. A fresh consideration of this policy as it was originally conceived and executed feels, therefore, timely as well as justified.

There is, of course, already a considerable body of literature on this subjectthough neither as extensive nor as up to date as is sometimes assumed. Indeed, while books on the Second World War have multiplied over the last twenty years, the buildup and causes of that catastrophe have been relatively neglected. Furthermore, while there have been many excellent books on appeasement, most of them have tended to focus on a particular event, such as Munich, or a particular person, such as Neville Chamberlain. What I wanted to do, by contrast, was to write a book which covered the entire periodfrom Hitlers appointment as German Chancellor to the end of the Phoney Warto see how the policy developed and attitudes changed. I also wanted to consider a broader canvas than that merely encompassing the principal protagonists. The desire to avoid war by reaching a modus vivendi with the dictator states extended well beyond the confines of government and, therefore, while the characters of Chamberlain, Halifax, Churchill, Daladier, and Roosevelt are central to this story, I have also examined the actions of lesser-known figures, in particular the amateur diplomats. Finally, I wanted to write a narrative history which captured the uncertainty, drama, and dilemmas of the period. Thus, while there is commentary and analysis throughout, my main purpose was to construct a chronological narrative, based on diaries, letters, newspaper articles, and diplomatic dispatches, which guides the reader through these turbulent years. In pursuit of this, I have been fortunate to have had access to over forty collections of private papersseveral of which yielded exciting new material. Not wishing to disrupt my narrative, I have not highlighted these finds in the text but, where possible, have favored unpublished over published sources in respect of both length and frequency.

A book on international relations naturally has an international scope. Yet this is primarily a book about British politics, British society, British diplomacy. Strange as it may now seem, Britain was still nominally the most powerful country in the world in the 1930sthe proud center of an empire covering a quarter of the globe. That America was the coming power was obvious. But the United States had retreated into isolationism in the aftermath of the First World War, while Francethe only other power capable of curtailing German ambitionschose to surrender the diplomatic and military initiative in favor of British leadership. Thus, while the British would have preferred not to become entangled in the problems of the Continent, they realized that they were, and were perceived as, the only power capable of providing the diplomatic, moral, and military leadership necessary to halt Hitler and his bid for European hegemony.

Within Britain, the choices that would affect not only that country but potentially the entire world were made by a remarkably small number of people. As such, the following pages may seem like the ultimate vindication of the high-politics school of history. Yet these men (and they were almost exclusively men) were not acting in a vacuum. Acutely conscious of political, financial, military, and diplomatic constraintsboth real and imaginedBritains political leaders were no less considerate of public opinion. In an age when opinion polls were in their infancy this was a naturally amorphous concept. Yet exist it diddivined from letters to newspapers, constituency correspondence, and conversationsand was treated with the utmost seriousness. For the majority of the 1930s the democratically elected leaders of Britain and France were convinced that their populations would not support a policy which risked war, and acted accordingly. But what if war was unavoidable? What if Hitler proved insatiable? And what if the very desire to avoid it made war more likely?