First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2011

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright James Barr, 2011

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of James Barr to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia, Sydney

Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi

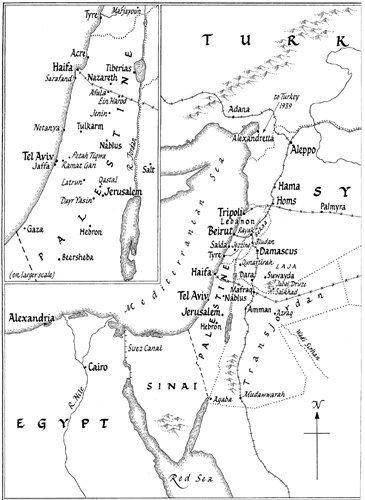

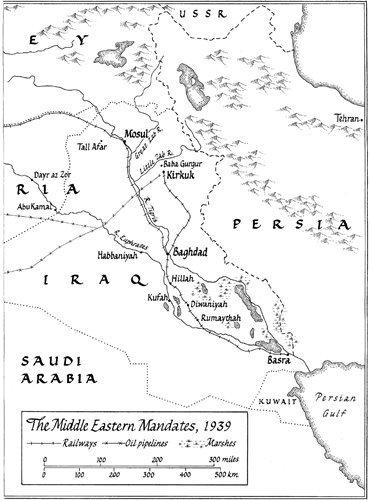

Maps on this Reginald Piggott

Every reasonable effort has been made to contact copyright holders of material reproduced in this book. If any have inadvertently been overlooked, the publishers would be glad to hear from them and make good in future editions any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-84737-453-0

eISBN: 978-1-84983-903-7

Typset in Sabon by M Rules

CONTENTS

THE CARVE-UP: 19151919

INTERWAR TENSIONS: 19201939

THE SECRET WAR: 19401945

EXIT: 19451949

PROLOGUE

IN THE SUMMER OF 2007 I CAME ACROSS A SENTENCE IN A newly declassified British government report that made my eyes bulge. Written by an officer in the British security service, MI5, in early 1945 but never published until now, it solved a mystery that had been puzzling the government. Who was financing and arming the Jewish terrorists who were then trying to end British rule in Palestine? The officer, just back from a visit to the Middle East, provided an answer that was astonishing. The terrorists, he reported, would seem to be receiving support from the French.

Adding that he had spoken to his counterparts in Britains secret intelligence service, MI6, the officer continued: We... know from Top Secret sources that French officials in the Levant have been clandestinely selling arms to the Hagana and we have received recent reports of their intention to stir up strife within Palestine. In other words, while the British were fighting and dying to liberate France, their supposed allies the French were secretly backing Jewish efforts to kill British soldiers and officials in Palestine.

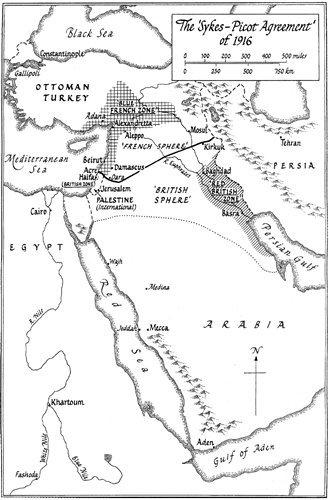

Frances extraordinary move marked the climax of a struggle for the control of the Middle East that had been going on for thirty years. In 1915 Britain and France, wartime allies then too, tried to resolve the tensions that their rival ambitions in the region were causing. In the secret SykesPicot agreement they split the Ottomans Middle Eastern empire between them by a diagonal line in the sand that ran from the Mediterranean Sea coast to the mountains of the Persian frontier. Territory north of this arbitrary line would go to France; most of the land south of it would go to Britain, for the two powers could not agree over the future of Palestine. The compromise, which neither power liked, was that the Holy Land should have an international administration.

Crude empire-building of this type had been common in the nineteenth century, but it was already unpopular by the time that the SykesPicot agreement was signed. Chief among its critics was the American president Woodrow Wilson. When the United States declared war on Germany in 1917 he criticised European imperialism and proposed that, when the war was over, subject and stateless peoples should be able to choose their own destinies instead.

In this new atmosphere, the British urgently needed a new basis for their claim to half the Middle East. Already in control of Egypt, they quickly realised that, by publicly supporting Zionist aspirations to make Palestine a Jewish state, they could secure the exposed east flank of the Suez Canal while dodging accusations that they were land-grabbing. What seemed at the time to be an ingenious way to outmanoeuvre France has had devastating repercussions ever since.

The British knew from the outset that this move risked causing deep anger in the Muslim world, but they were confident that they could overcome it. They believed that the Arabs would recognise the economic advantages of Jewish immigration and that the Jews would long be grateful to Britain for helping them realise their dream. Both assumptions proved to be wrong. When Jewish immigration triggered Arab outrage, British attempts to keep the peace by slowing change swiftly exasperated the Jews.

Under mandates granted by the League of Nations, Britain took control of Palestine, Transjordan and Iraq; France, Lebanon and Syria. Both powers were supposed to steer these embryonic countries to rapid independence, but they immediately began to drag their feet. The Arabs reacted angrily as the freedom they had been promised continually receded before them like a mirage. The British and the French blamed one anothers policies for the opposition they each began to face. Each refused to help the other address violent Arab opposition because they knew that they would only make themselves more unpopular by doing so. For almost two years in the 1920s, the British ignored frequent French requests to stop the rebels who were fighting their forces inside Syria from using neighbouring, British-controlled, Transjordan as a base. The French in turn shrugged when the British asked them to clamp down on the Arabs who were taking sanctuary in Syria and Lebanon during their insurgency in Palestine in the second half of the 1930s. Lacking neighbourly support, both France and Britain resorted to violent tactics to crush protest that only enraged the Arabs further.

The French had long believed that the British were actively aiding Arab resistance to their rule, but up until the outbreak of the Second World War this suspicion was unfounded. The fall of France in 1940, and the subsequent decision by the French in the Levant to back the Vichy government, ended both sides reluctance to interfere in one anothers problems. In June 1941 British and Free French forces invaded Syria and Lebanon to stop the Vichy administration providing Germany with a springboard for an offensive against Suez. After the Vichy French surrendered a month later, the British government entrusted the government of Lebanon and Syria to the Free French. When that move caused Arab anger British officials decided that the best way to divert attention away from Palestine was to help both Syria and Lebanon gain their independence at French expense. With significant British assistance the Lebanese did so in 1943. The French found out that the British were plotting with the Syrians to the same end the following year.

The French discovered that the Zionists shared their appetite for revenge, for by now Jewish opinion had moved decisively against the British. In 1939 the British, in a bid to placate the Arabs, had imposed tight immigration restrictions that prevented large numbers of Jews fleeing Nazi Germany from reaching safety in Palestine. When news of the systematic nature and the scale of the Holocaust emerged, many Jews decided that it was time to throw the British out. Britains appeasement of the Arabs terrorism before the war had shown that violence worked. As this book reveals, the French now secretly offered support to Zionist terrorists who shared their determination to drive the British out of Palestine.