Peter Mangold is a Visiting Academic at the Middle East Centre, St Antonys College, Oxford. He is a former member of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office Research Department and the BBC Arabic Service. He has written extensively on British foreign policy and is the author of The Almost Impossible Ally: Harold Macmillan and Charles de Gaulle and Britain and the Defeated French: From Occupation to Liberation 19401944 , winner of the 2013 Edith McLeod Literary Prize (both I.B.Tauris).

What the British Did is an enjoyable and profitable read

Wm. Roger Louis, Professor of History, University of Texas, Austin

This book is a major contribution to the existing literature on Britains encounter with the Middle East. It is unique in offering a comprehensive survey of over two centuries of history. And it has the added merit of exploring many different aspects in Britains relationship with this complex, volatile, and endlessly fascinating region.

Avi Shlaim, author of The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World

For Meridel Holland

Contents

List of Maps and Illustrations

Acknowledgements

M y thanks to Clare Brown, Professor Raymond Cohen, John Eidinow, Roger Hardy, Dr Meridel Holland and Valerie Yorke for taking the time and trouble to read all or parts of the manuscript (though, needless to say, responsibility for the final text is my own). At St Antonys College, Oxford I am most grateful to the librarian the Middle East Centre, Mastan Ebtehaj, for her patience as I discovered more and more relevant volumes, and to the archivist, Debbie Usher, for guiding me through the Centres fascinating collection of photographs. I am also grateful to Lester Crook at I.B.Tauris for his support for the project. I should also acknowledge one other considerable debt, to the late Philip Windsor of the London School of Economics, who supervised the thesis which many years later led to this book.

Abbreviations

AIOC (previously APOC) | Anglo-Iranian Oil Company |

APOC | Anglo-Persian Oil Company |

BJMES | British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies |

EEC | European Economic Community |

EU | European Union |

INS | Intelligence and National Security |

IPC | Iraq Petroleum Company |

ISIS | Islamic State in Syria and the Levant |

JIC | Joint Intelligence Committee |

JICH | Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History |

MECA | Middle East Centre Archive, St Antonys College, Oxford |

MES | Middle Eastern Studies |

MI5 | Security service |

MI6 (also SIS) | Britains external intelligence-gathering service |

RUSIJ | Journal of the Royal United Services Institute |

SAS | Special Air Service |

UAE | United Arab Emirates |

UAR | United Arab Republic |

Introduction

The Pedigree of a White Stallion

Huree Babu: You sit tight, Master OHara [] It concerns the pedigree of a white stallion.

Kim: Still? That was finished long ago.

Huree Babu: When everyone is dead the Great Game is finished. Not before.

Rudyard Kipling, Kim (London, 1944 edn, p. 316)

A t South Shields on the estuary of the Tyne and Wear are the outlines of a Roman fort. Its name is surprising Arbeia, The Place of the Arabs, an apparent reference to one of the Roman units stationed there. This may have been an irregular unit of bargemen from the River Tigris, but archers from Syria were also known to have been stationed along Hadrians Wall. The Roman Empire provides the earliest link between England, then its most northerly possession, and what is today known as the Middle East. Egypt, modern-day Syria and Israel, along with Mesopotamia, were also Roman provinces.

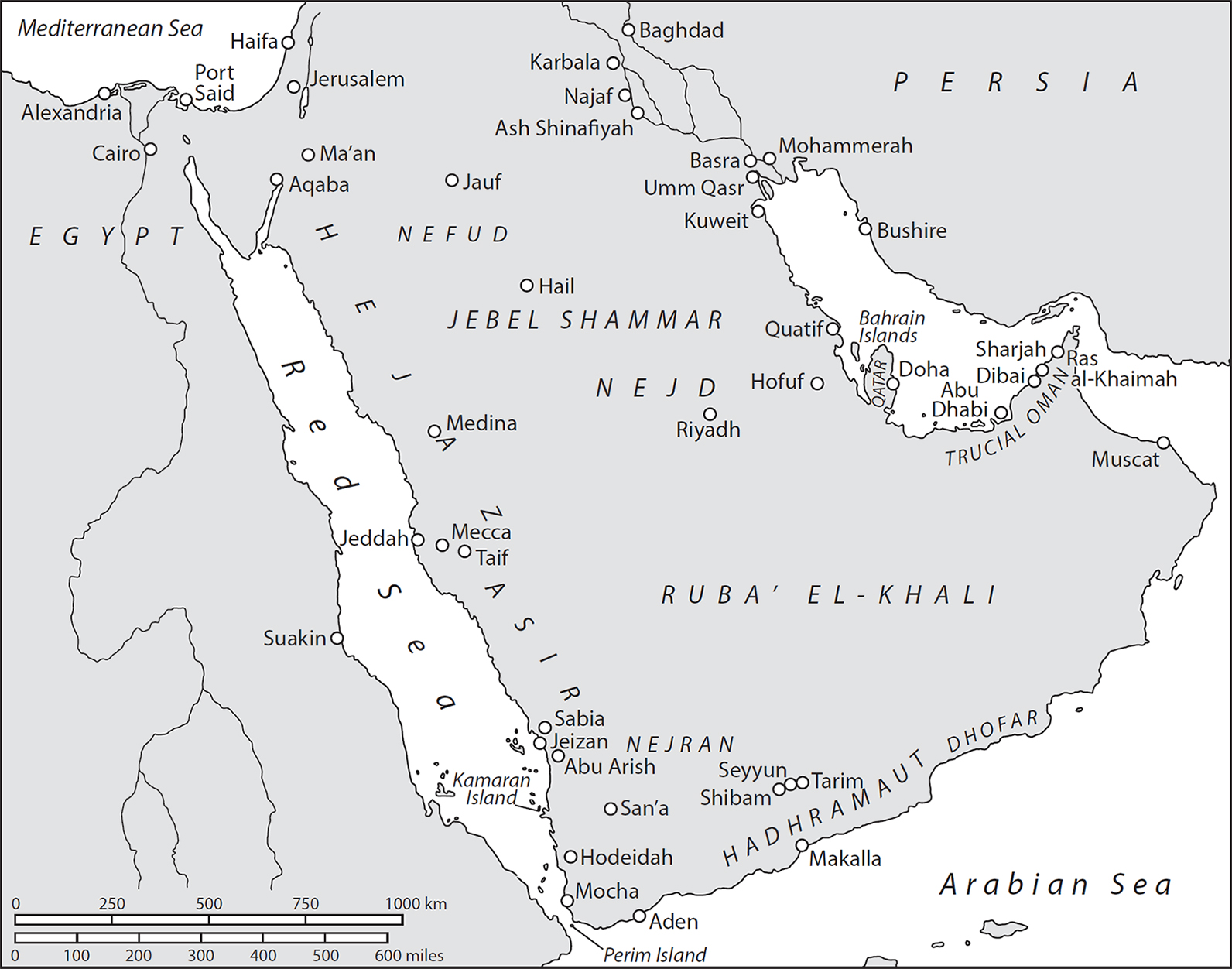

The first English soldiers to go to the Middle East went during the Crusades, the two-century conflict for the control of the Holy Land between Christianity and Islam, beginning at the end of the eleventh century AD ; Richard I took Acre in 1191. Thirty years later, a Palestinian soldier, St George, was adopted as Englands patron saint. English traders were going to the Middle East in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Her husbands to Aleppo gone, master o th Tiger intones one of the witches in Macbeth , the Tiger being the name of a ship. The Levant Company had in 1581 been granted a monopoly of trade with the Ottoman Empire, and for the next 240 years appointed all the commercial and diplomatic representatives in the Levant. The East India Company, established in 1600, opened its first factory or trading station at Jask on the Persian side of the Gulf of Oman in 1616. Its first commercial foray to Bussorah, todays Basra, took place in 1635.

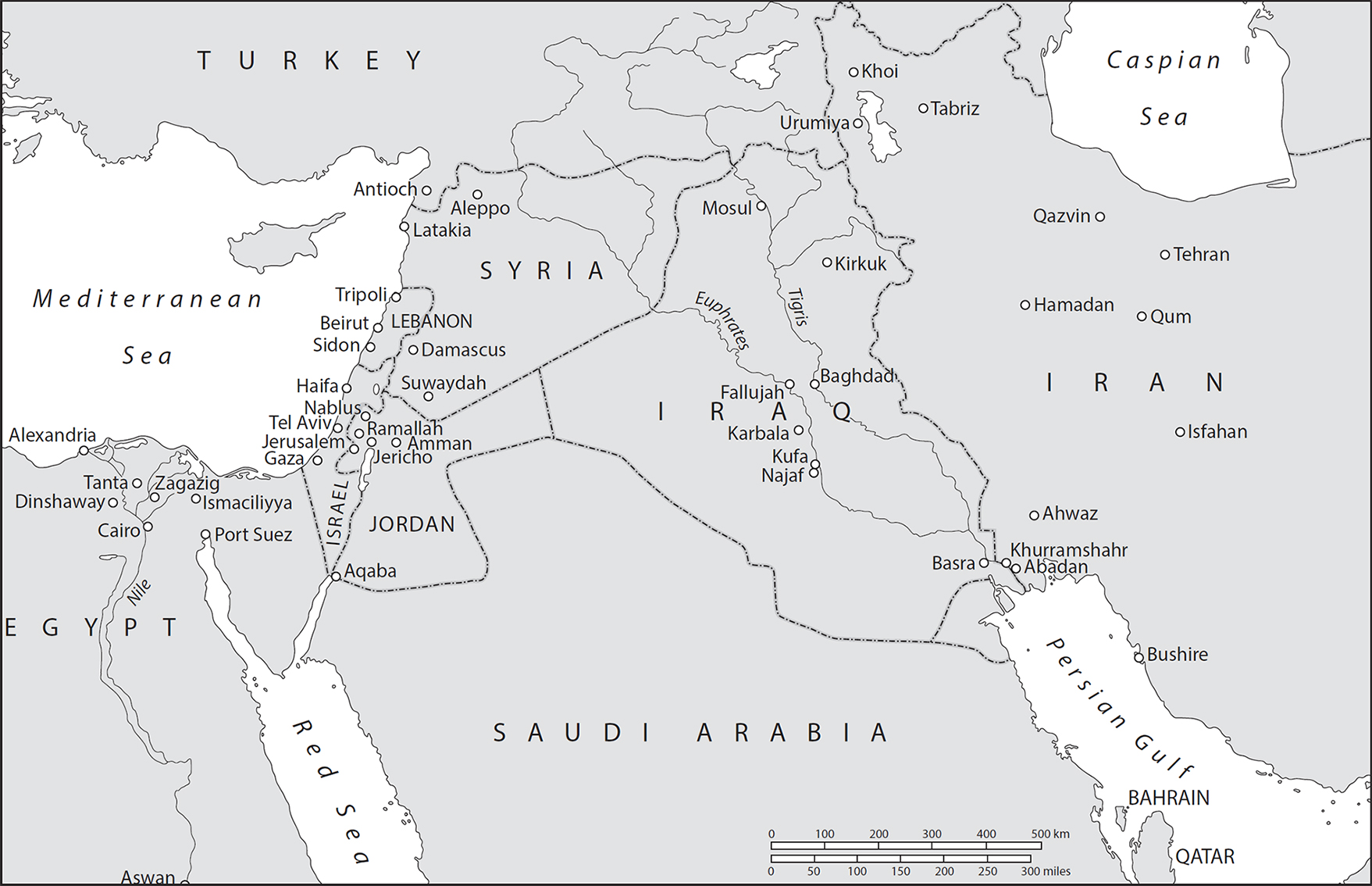

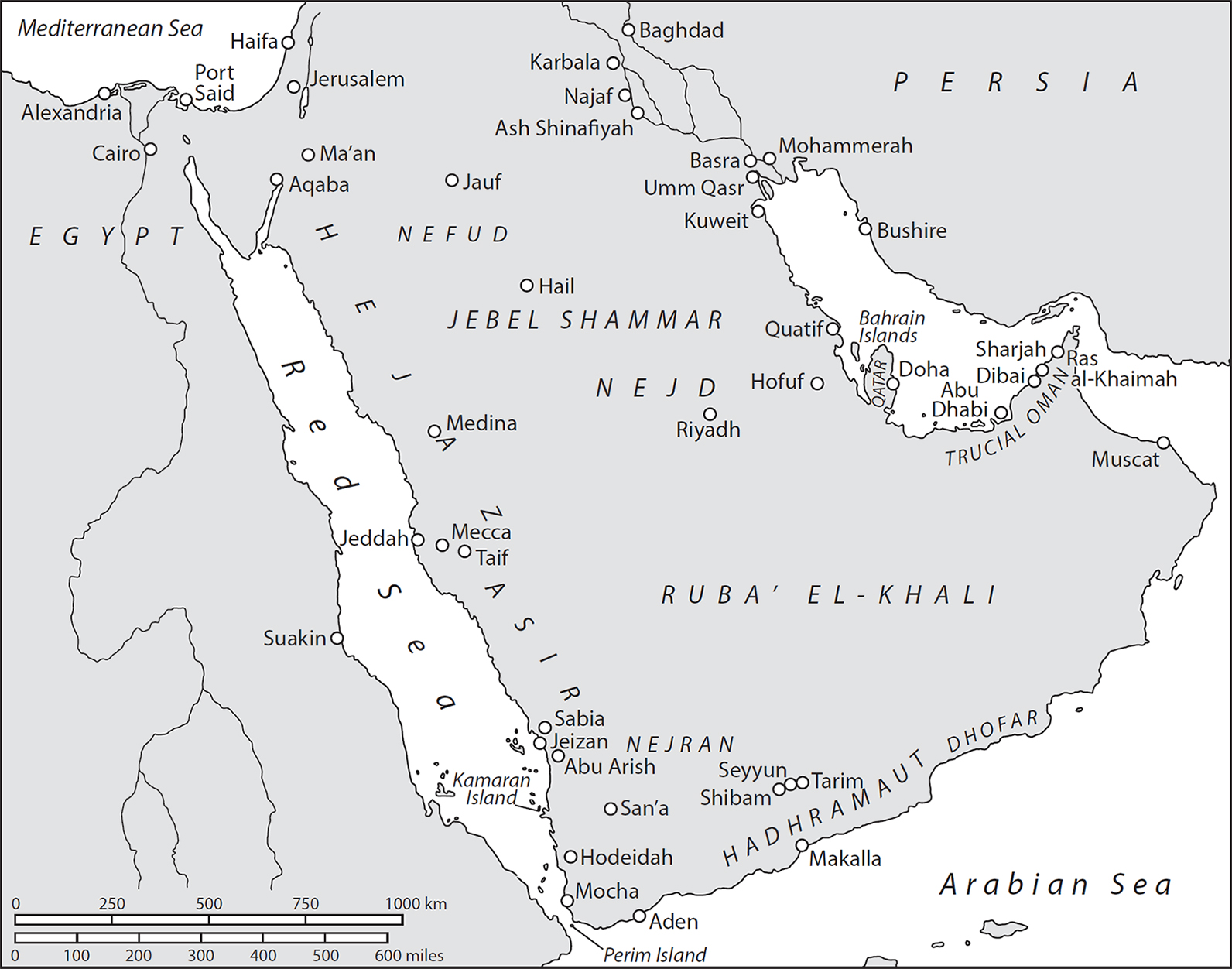

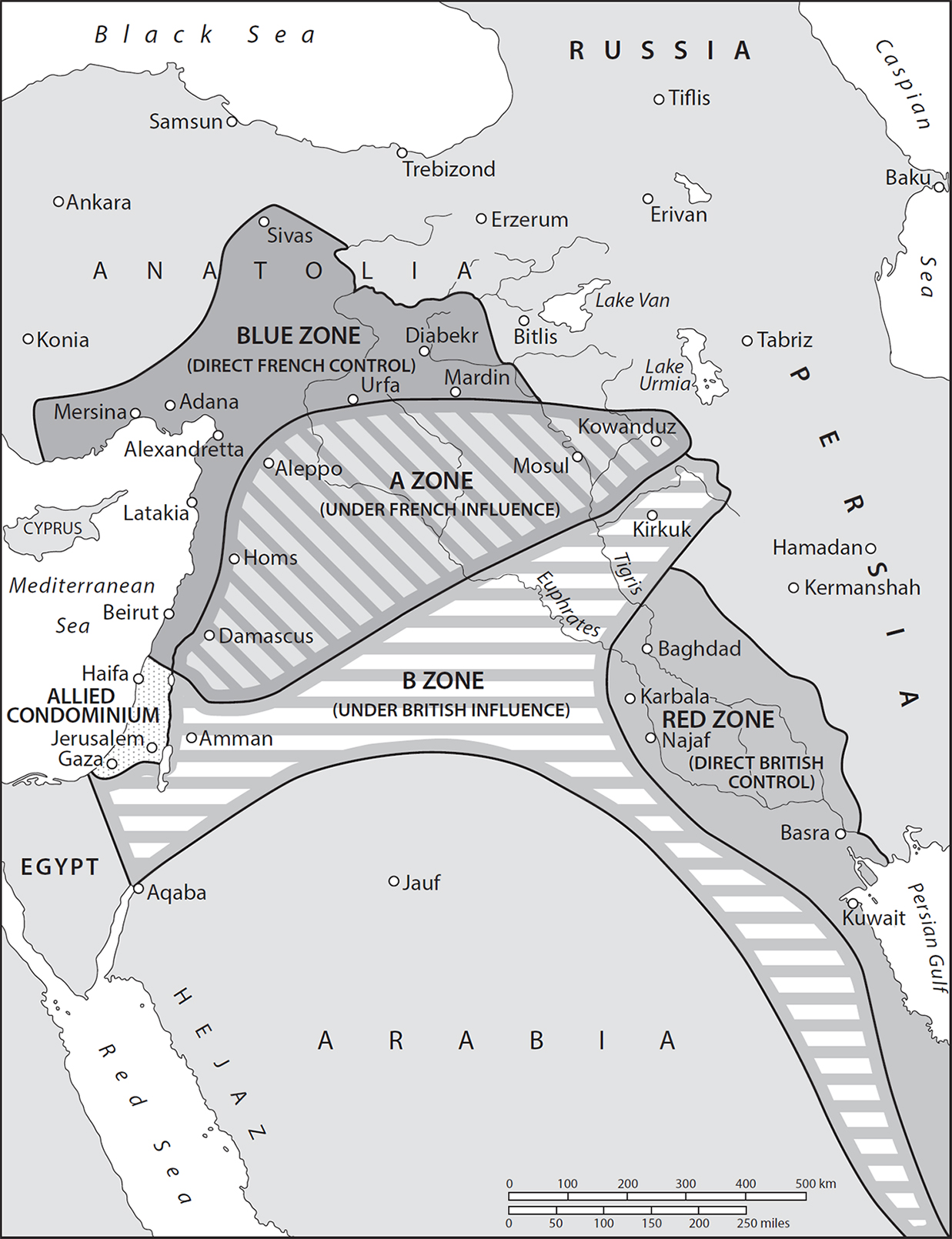

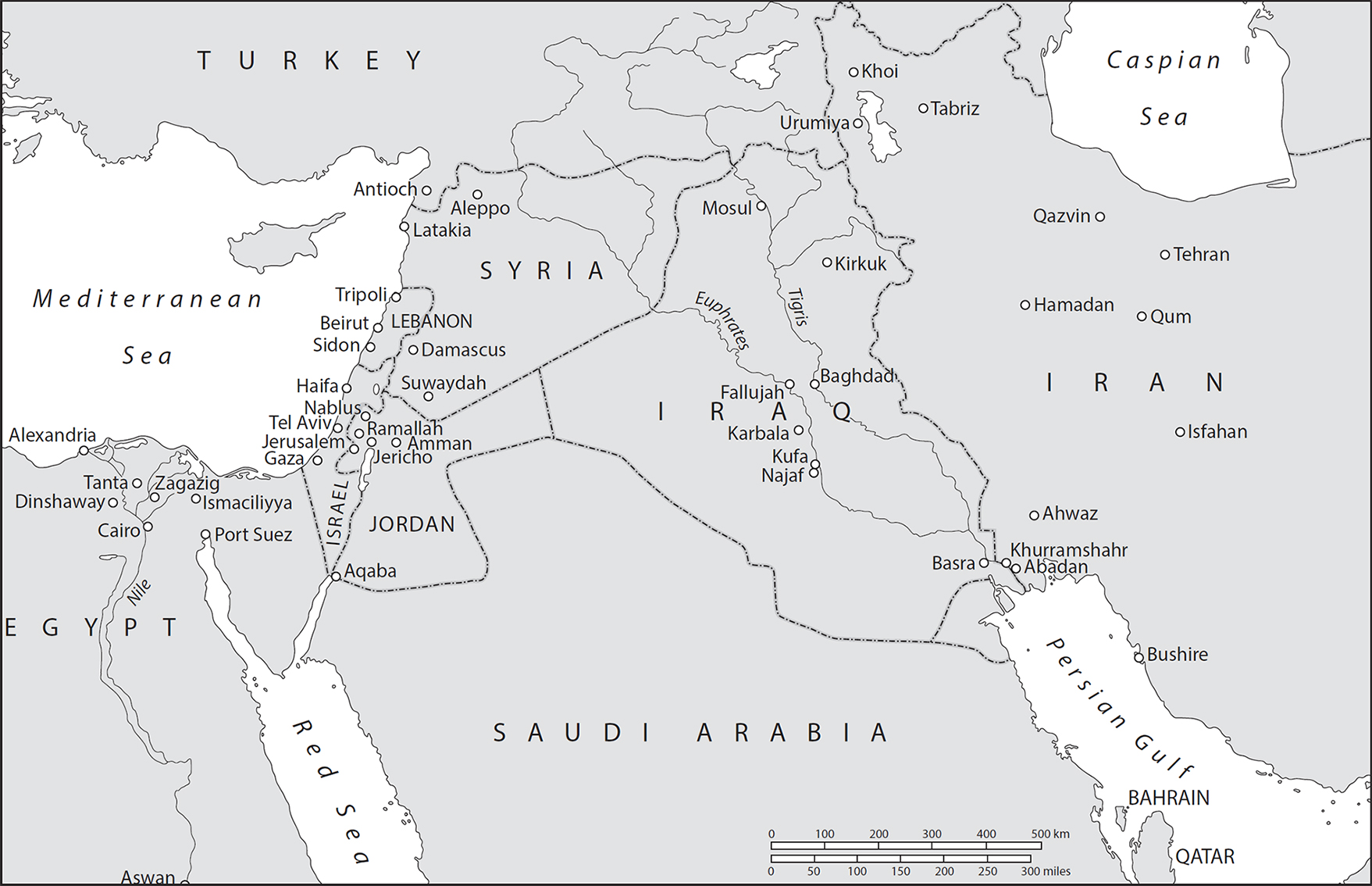

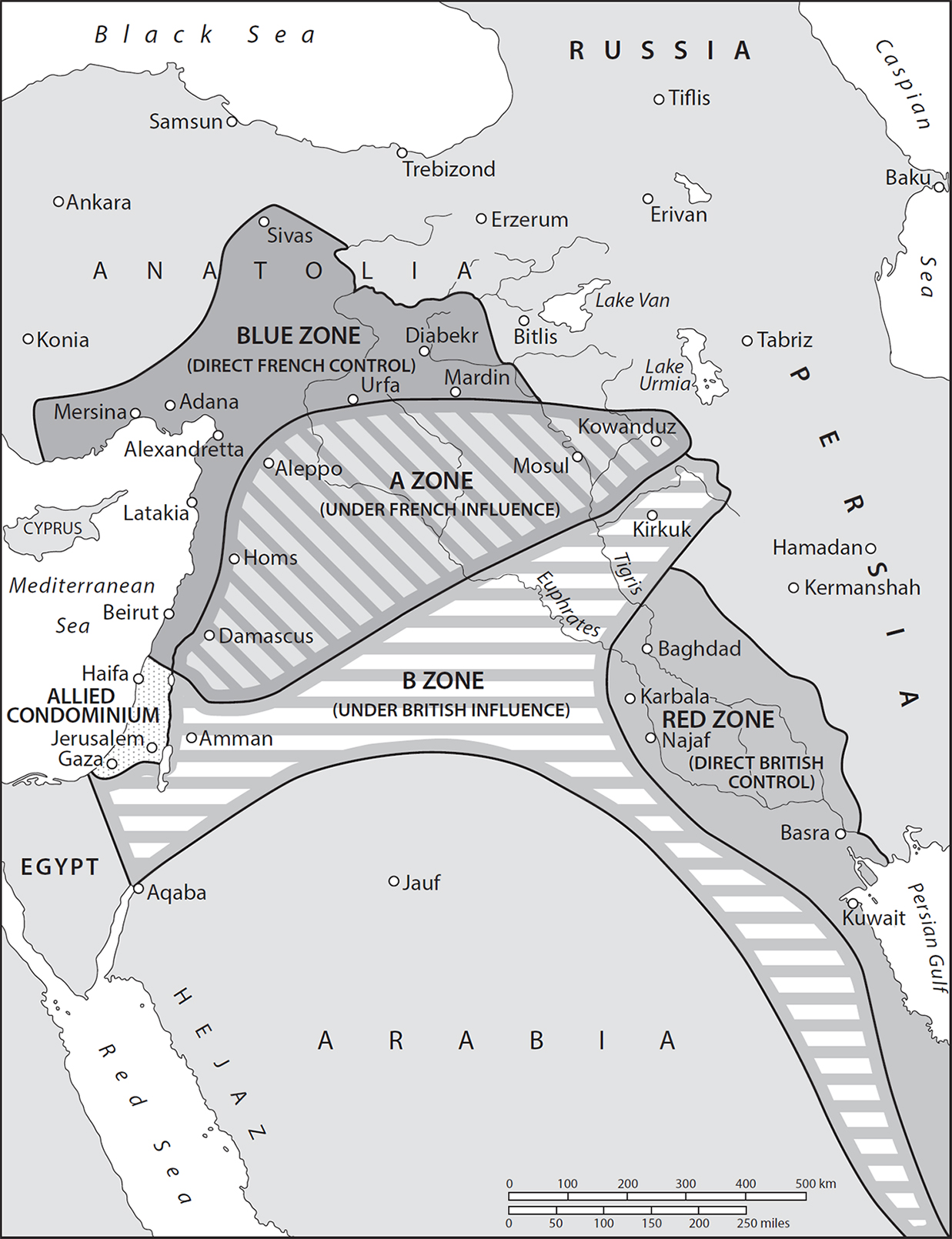

It was not, however, until the Napoleonic wars that the expanding British Empire began to take a serious interest in the Middle East, understood here as the region between the Libyan desert in the west and Persias eastern border with Afghanistan. Outside Europe, Britains major eighteenth-century wars had been fought primarily in India, America and the Mediterranean. The combination of the growing British presence in India and French intervention in Egypt in 1798 first drew in the British to the Middle East. The possession of Egypt by any independent power, declared the Secretary of War, Henry Dundas, would be a fatal circumstance to the interests of this country. Two British expeditions to Egypt followed, along with treaties with Persia and Muscat, and a brief occupation of Perim Island at the mouth of the Red Sea. Around the same time the East Indian Company sent a naval expedition to the Persian Gulf, to deal with what it viewed as piracy.

Over the next two centuries, the Middle East held an importance to Britain, unmatched by any other region of the world. An expanding European world power, the heart of whose empire lay in the Afro-Asian world, was bound to concern itself with the control of the strategically critical crossroad region linking Europe, Asia and Africa. The Middle East became the swing door of empire, or more colloquially, the Clapham junction of imperial communications. It was also an important piece of strategic real estate, the point at which the Empire could be severed, from which power could be projected, which thus needed to be denied to rivals and enemies. In the first half of the twentieth century came the discovery of oil. Today regional violence threatens to spill over onto the streets of Britain. Twenty-first-century politicians are as conscious as their nineteenth-century predecessors that the holy sites of Islam, as also of course of Christianity and Judaism, lie in the Middle East.