IN AN EFFORT to simplify transliteration from Arabic, Persian and Ottoman Turkish for ease of reading, I have dropped diacritical marks (other than the medial ayn and hamza), as well as, in the cases of toponyms and well-known proper names, the definite article al-. Exceptions are terms in italics, titles of books and citations. Wherever possible, I have preferred brief, familiar and/or anglicized terms, toponyms and proper names to transliterated ones. This may at times risk anachronism or confusion, as in my use of Syria for al-Shm or Iraq for al-Irq, but I take care to situate such toponyms in their historical context. I have adopted modern Turkish spellings for Ottoman rulers and widely accepted anglicizations of other well-known rulers (as in Gamal Abdel Nasser), but I have transliterated other names and terms from Arabic, Persian and Ottoman Turkish following the system in the International Journal of Middle East Studies. All dates are common era (CE), and death dates are preceded by d. and in parentheses. The bibliography lists only published sources, with a focus on those that will be accessible to the general reader, but full citations for unpublished manuscripts, archival documents, rare books and related websites can be found in the references. Similarly, captions serve as brief descriptors of illustrations, but full discussions and information about sources are provided in the text and accompanying references.

I NTRODUCTION : O N THE M IDDLE E AST AND M APPING

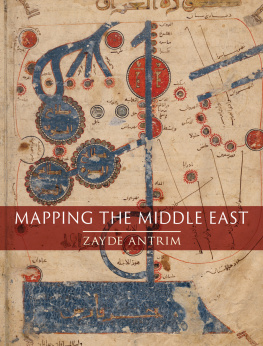

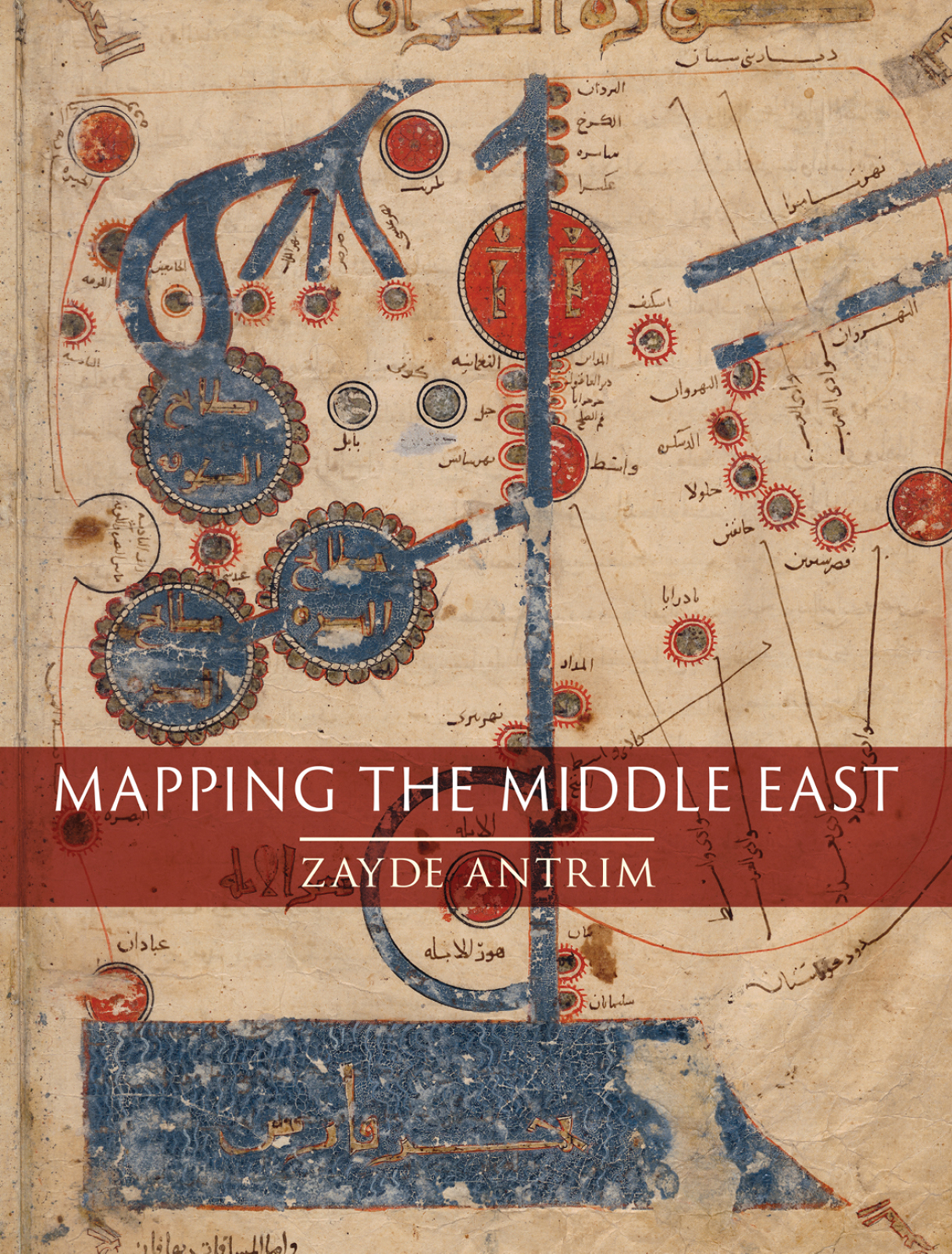

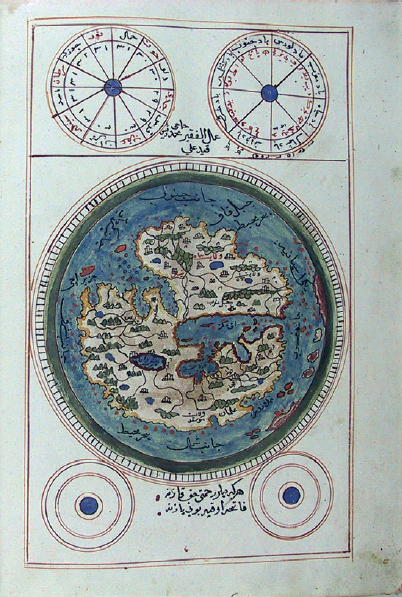

T his book is a history of mapping in and of a world region commonly identified in English today as the Middle East and associated with the history of Islam. This shifting region and its constituent parts have been conceived, named and mapped in many different ways over the past millennium. By focusing on mapping-from-within, I argue, first and foremost, that the people of the region have been making maps of their own worlds for centuries. This may seem obvious, but most histories of cartography are still strikingly Eurocentric, and those that do deal with other parts of the world tend to emphasize their encounters with Europe and European maps from the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries on. By contrast, this book spans a thousand years, from the eleventh to the twenty-first centuries, and only one of its chapters is devoted to maps made by Europeans in the context of colonial encounters. Nonetheless, my second argument is that those encounters and the subsequent rise of the nation-state have severely constrained cartographic and spatial thinking, both within the region and without, making it difficult to visualize other possibilities. In this light, engagement with the pre-colonial, pre-national period is intended not only as an assertion of the chronological depth of indigenous mapping traditions, but as nourishment for our geographical imaginations.

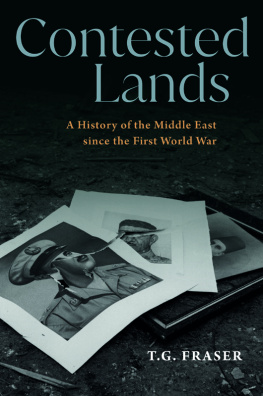

Thus, I use the term Middle East here and in the books title as a kind of shorthand, in lieu of toponyms that are no longer in use, that would sound unfamiliar to many readers, or that are themselves partial and problematic. I also use it with considerable reluctance, for I am all too aware of its baggage. However, it remains the term most likely to conjure a mental map that features the places discussed inthis book. Unfortunately, it is also likely to conjure a host of negative images and generalizations that stem from the history of its use, which is inseparable from the history of European and North American imperialism. The term started circulating in Europe in the nineteenth century and was used in particular by the British to distinguish colonial projects in India and Central Asia (the Middle East) from foreign policy toward the Ottoman Empire (the Near East). At the very least, therefore, these terms were expressions of directional orientation particular to the people of northwestern Europe; the same lands, for instance, would be considered to some degree west of people living in China. But these terms were not merely expressions of directional orientation. Their emergence was inseparable from the imposition of European political and economic domination on the rest of the world, as well as accompanying discourses that distinguished a modern, civilized West from a traditional, backward East, in need of proper management. In this context, the use of such terms reflected assumptions of Western superiority and entitlement and helped legitimize European control over far-flung lands and peoples.

The term Middle East would gain additional traction, and a higher degree of specificity, in the middle of the twentieth century, just as the United States launched its own bid for global dominance. In the period after the Second World War, American journalists, policy-makers and scholars increasingly used the term to refer to a strategically significant area, stretching in most formulations from Libya or Egypt to Iran or Afghanistan, in which the twin priorities of U.S. foreign policy were to build a bulwark against Communism and ensure access to cheap oil. To these ends, the U.S. government funded Middle East Studies programmes in institutions of higher education, which produced a new generation of intellectuals whose very training was predicated on the existence and coherence of such a region. This went hand-in-hand with growing media attention, which tended to trade in stereotypes leering Arabs, extravagant wealth and fanatical Muslims, among others. In the past two decades, American obsession with the Middle East has only grown, though the post-9/11 War on Terror has replaced the Cold War as the chief paradigm for foreign policy in the region. This has resulted in protracted U.S. military occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as bombing campaigns, drone strikes and proxy wars that have

Indeed, in order to problematize the idea of the Middle East, it is necessary to use the term in the first place, but here I intend it mainly as a way of ensuring that we are all on the same page or map before travelling into the deep past and retrieving its forgotten geographies. While there are other widely understood terms I could use (and will, elsewhere in this book) most notably some combination of subcontinental designations, such as West Asia/North Africa these too have limitations, only one of which is their comparative unwieldiness. The idea of the continents has its own history, along with its own baggage. Efforts to delimit the continent of Europe and to distinguish it from Asia, for instance, have been predicated on the same kinds of assumptions of European superiority as discourses contrasting West and East. Whatever term I use, the point is that people have imagined meaningful world regions on scales similar to that of the Middle East, and with considerable overlap, in many ways over the past thousand years. Parameters have shifted and the modes of mapping have varied, but regional or superregional thinking is nothing new, nor is it the preserve of the West. That said, this book is not intended to replace the Middle East with a more accurate or authentic toponym, but to emphasize the contingency of all methods of dividing the world and endowing those divisions with meaning. They are never measurable in terms of their proximity or faithfulness to an outside reality whether geographical, historical or political but they are, rather, always already implicated in that reality. In taking this approach, I hope to contribute to ongoing conversations that push us to think critically about the ways people have described, named and visualized the world, both in the past and today.