I am most grateful to my editor, Lisa Thomas, who is as effective and efficient as she is calming and helpful. We worked together on the DK Atlas of World History and I am delighted to see that the team still works well. Thanks too to Sonja Brodie for copy-editing the book, to Jen Veall for her creative picture research and Nicola Liddiard for her elegant design. I have benefited from the comments of Heiko Henning on an earlier draft and am also grateful to Yingeong Dai, Mike Dobson, Spencer Mawby, David Parrott, Karsten Petersen, Kaushik Roy, Don Stoker, Stag Svenningsen, Ken Swope and Harold Tanner for answering questions on particular points.

DETAIL OF THE SIEGE OF MALTA IN 1565. BY MATTEO PEREZ DALECCIO (1547-1616) One of a series of thirteen frescoes that decorates the Throne Room of the Grandmasters Palace in Valletta. The position of the Ottoman armies on the island is shown in great detail.

THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY: FIRST NOTIONS OF MILITARY MAPPING

War requires a spatial as well as temporal sense and awareness. At the tactical level, that of battles, it requires the detailed understanding of the relationships between place and terrain, notably height, slopes and water features such as rivers and marshy ground. Each of these was, and is, significant for the tasks set for military units and for their relative effectiveness in discharging them. At the operational level, that of campaigns, the conduct of war requires an understanding of routes and of the relationships between place and terrain over the area of campaign. These are necessary for effective planning both about advances and concerning supplies. At the strategic level, there are requirements for geopolitical information so that challenges and opportunities can be grasped and priorities determined.

All of these levels involve the equations of force and space, and each requires maps: maps to present, maps to understand, and maps to convince. This book covers the variety of different ways in which maps have accompanied war, notably for geopolitical consideration, strategic planning, operational purposes, tactical grasp, news reporting and propaganda. In doing so, it considers the different stages of conflict preparation, planning, initiation, waging, outcome and retrospect and assesses the manner in which maps framed a particular perception of war at various scales and to very different audiences, from strategists to tacticians, from the military to the public, from those who were present to those who were distant. The application of mapping technologies developed in peacetime is assessed, as is their use in wartime. The entire situation in recent centuries is one of dynamism, as opportunities are grasped, tested and used.

For most of history, and still to this day, the relevant maps have overwhelmingly been mental maps, the understanding of place in the minds eye. These were ready means to help consideration and exposition. For example, the plan of an ambush or a fort might be drawn with a stick, a finger in the dirt or in powdered sand, sketched in the air or described with words. These methods did not leave records, written or otherwise, that survive, and that is a crucial point when looking at the mapping of war. It is a particularly significant point for pre-modern warfare. Nevertheless, pre-modern armed forces carried out complex operations that would have required a foreknowledge of terrain. How that knowledge was conveyed is less clear, but oral report was the key means. In the Roman sources, there are not references to the use of maps on campaign, but there are many references to scouts being sent out to learn about the locality. This suggests that an aural and visual approach to mapping was used, rather than a written system.

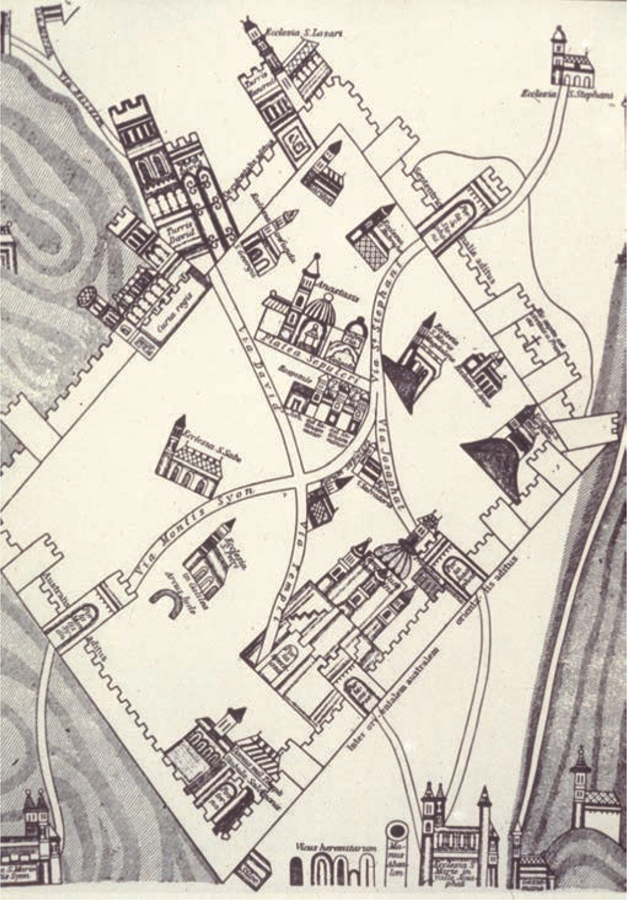

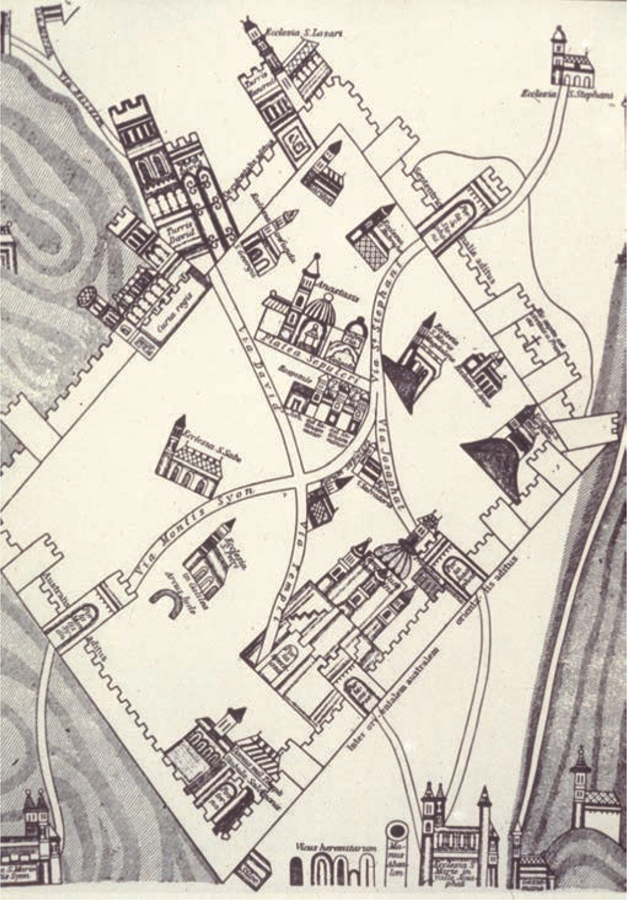

FLEMISH MAP OF CRUSADER JERUSALEM, BEFORE 1167 A Flemish map of a city that was a defensive stronghold as well as a religious and governmental centre. Jerusalem had been stormed in the First Crusade in July 1099, with heavy casualties for the defenders and the civilian population. However, the defeat of the army of the Kingdom of Jerusalem at Hattin in 1187 was followed by the loss of both Jerusalem and Acre. The destruction of the field army left the fortress garrisons in a weak state. Jerusalem itself surrendered after its walls were undermined and breached. Its fate indicated that the weaknesses of fortified positions included their vulnerability when denuded of troops in order to create a field army, as well as the psychological effects of the defeat of such an army. These were the key elements, not the fact that Jerusalem had not benefited from the development of the concentric plan for fortifications, a plan that owed much to better Muslim siege techniques.

Oral report went on being significant, but sometimes with disastrous effect, as during the Crimean War when, as a result of misunderstanding orders, the British Light Brigade cavalry charged directly into Russian artillery at Balaclava in 1854. This was a classic instance of poor situational awareness and was not redeemed by the bravery displayed.

DRAWING OF IMOLA. BY LEONARDO DA VINCI, 1502 The strength of fortifications had become a more prominent issue once the Italian Wars broke out in 1494, with cannon playing a role in the successful French invasion of Naples that year. This began a period of conflict in which Pope Alexander VI, eager to expand the Papal States, instructed his second son, Cesare Borgia, to subjugate the region of the Romagna in eastern Italy. Cesare Borgia started by capturing the town of Imola in 1499 and continued to make conquests until 1503, when the death of his father was followed by his arrest under the orders of the new Pope, Julius II. Da Vinci was employed to survey Imola and to suggest how best to improve its defences. In Da Vincis aerial view, the city emerged clearly as a defensive system. The significance of the moat was readily apparent. This approach was much more effective than that of adopting an oblique perspective and displaying buildings in elevation.

THE OTTOMANS VERSUS CHARLES V, 1535. ENGRAVING BY FRANZ HOGENBERG In 1534, Tunis was captured from Mulay Hasan, its pro-Spanish ruler, by Hayreddin Barbarossa, the Ottoman Grand Admiral and the key figure in Algiers. This was part of the Ottoman attempt to consolidate their power in North Africa after their conquest of Egypt in 1517. The Emperor Charles V, who also ruled nearby Sicily as well as Spain, responded in 1535 with a major expedition that included 82 war galleys and more than 30,000 troops. The expedition, which reflected Spanish capability for force projection, was in large part paid for with Inca gold from South America which repaid loans from Genoese bankers. Mounted in ferociously hot conditions, this expedition displayed amphibious capability and success in fighting on land. The fortress of La Goletta at the entrance to the Bay of Tunis, although defended by a large Ottoman garrison, was successfully besieged, falling on 14 July. A week later, Tunis was captured and sacked. Thousands of Christians were released from slavery, while thousands of the local population were slaughtered and large numbers sold as slaves. Charles installed a pro-Spanish Muslim ruler. This was a high-water mark for Spanish attempts to bridge the western Mediterranean, which did not appear to contemporaries as a border.