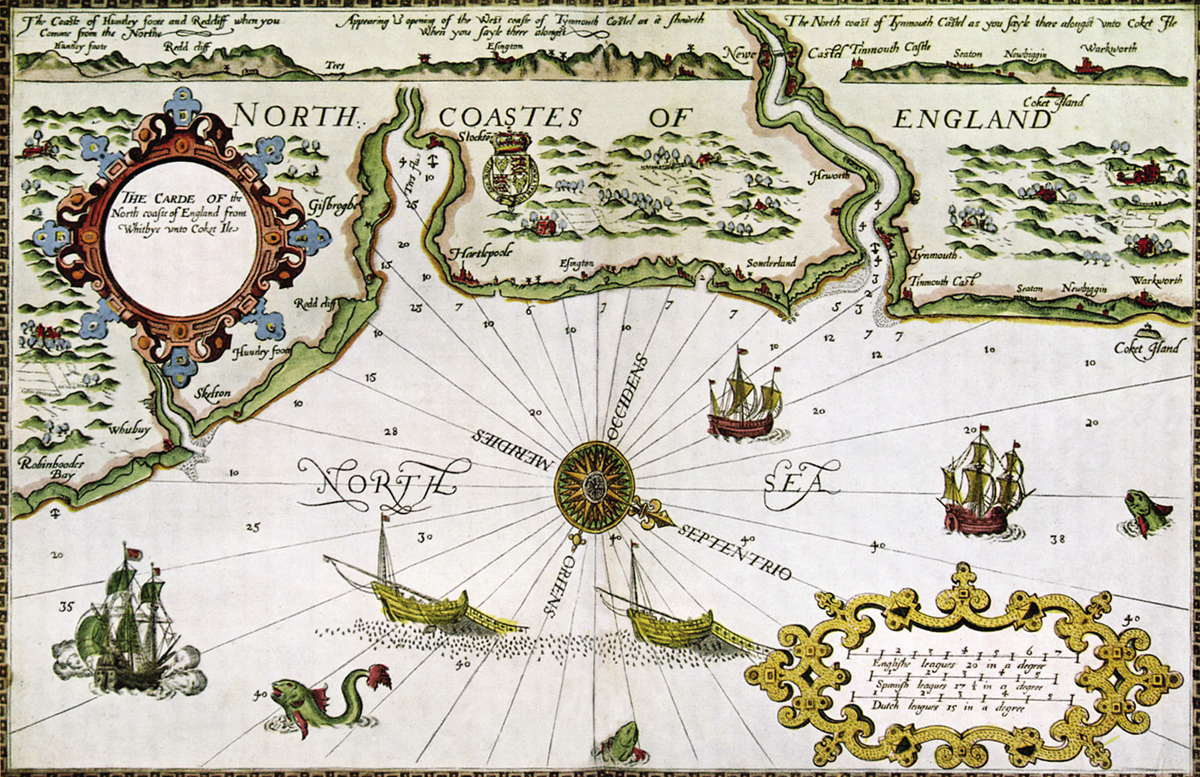

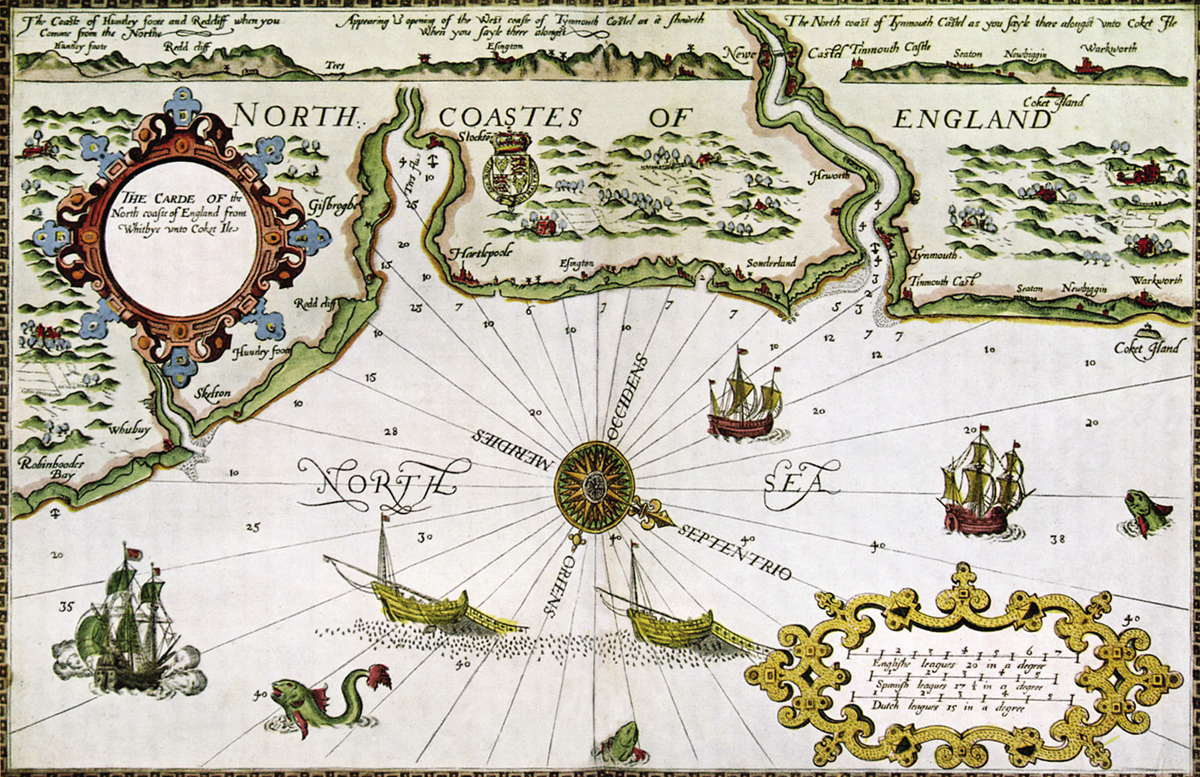

Map of the north coast of England from The Mariners Mirrour, 1588, a ground-breaking publication designed for sailors. As well as navigational information, the book contained 45 large-scale coastal views of European harbours and ports. The maps were engraved by three Flemish map-makers De Bry, Hondius and Rutsinger and one Englishman, Augustine Ryther.

FOR EILEEN COX

CONWAY

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

This electronic edition published in 2018 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY, CONWAY and the Conway logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain in 2018

Copyright Jeremy Black, 2018

Illustrations as indicated

Jeremy Black has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work

For legal purposes the Acknowledgements constitute an extension of this copyright page

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN: 978-1-8448-6517-8 (HB)

ISBN: 978-1-8448-6516-1 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-8448-6515-4 (ePDF)

Design by Nimbus Design

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletter.

Contents

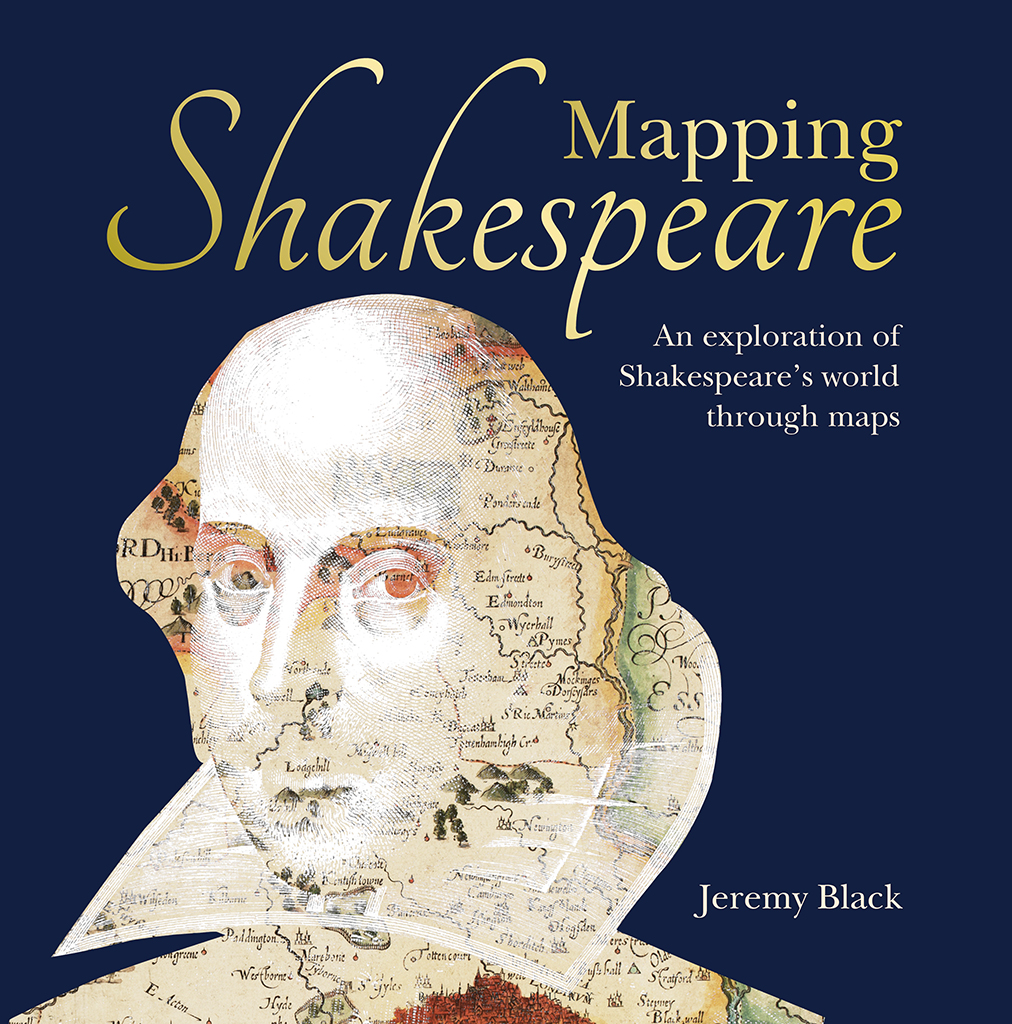

The Chandos portrait of William Shakespeare (c.160010) has never been fully confirmed to be a likeness of the playwright. It has often been ascribed to his friend and fellow playwright, Richard Burbage who was also a talented painter.

Preface

Shakespeares world was that of space and time, the experiences and understandings he had, and those of the spectators and readers. These, in turn, were dynamic in nature due to the amazing explorations of the age and the descriptions of them that were published, as well as the appearance of historical works that threw light on the past. For the first, Shakespeare lived in the age of voyagers into the unknown such as Francis Drake, the first Englishman to sail round the world, Martin Frobisher and Henry Hudson and in the shadow of those of an even bolder set of trailblazers, notably Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, and Ferdinand Magellan. Exploration by these men, discoveries to Europeans (but not to those who were already aware that they existed), affected not just the knowledge of places and peoples that was available, but also the very way of seeing and explaining the world. This was the case from the existence, number and shape of its continents, particularly the understanding of the existence and scale of the Americas, to the extent of the worlds circumference; and from the projections employed by map-makers to the perspectives deployed. Maps and globes literally changed, and these changes, and the very nature of change itself, encouraged an awareness of a world that was at once known and knowable and yet also in the process of discovery and thus uncertain.

Shakespeares choice of setting for his works reflected this changing geography. In his plays, there were places that were very familiar and/or well understood by his audiences notably the street life and social geography of London. However, there was also an understanding of the geography of England, such that the places where Shakespeare set action, for example Dover, Bristol, London, Southampton and York, were understood, even though a smaller percentage of the population would have travelled widely in England than is the case today. Moreover, some places abroad were close enough to be presented as similar, notably in order to make archetypal points, such as the Vienna of Measure for Measure and the Venice of The Merchant of Venice.

Yet Shakespeare also moves further afield: Europes peripheries and neighbours come into view in the shape of characters from them, such as the Prince of Morocco who was an unsuccessful suitor of Portia in The Merchant of Venice, or a unit of Muscovite troops in Italy in Alls Well That Ends Well. Such individuals resonated with the news of Shakespeares lifetime. For instance, the Moroccans had routed a Portuguese invasion in 1578, and Elizabeth I of England had subsequently sought an alignment with Morocco against Spain. Under Ivan IV, the Terrible (r.15331584), Russia had become a major and expansionist power, and England had sought good relations with that country, too.

Turning to potent non-Western powers, there is mention of the threat from the expansionist Turkish Empire; it is this that leads Othello, a Venetian general, to the Venetian colony of Cyprus although by the time Shakespeare wrote the play it had actually already fallen to the forces of the Turkish Sultan, Selim II. In addition, in Alls Well That Ends Well there is mention of the Turks fighting the Safavids of Persia, which they did for much of the period from the 1500s to the 1630s. Shakespeare does not engage in a comparable fashion with China, India and Japan, but the sense of new lands is represented by the voyages taken by characters, and their shipwrecks on strange shores. Distance alone should place Prosperos Island in The Tempest, its travellers shipwrecked on a voyage from Tunis to Italy, somewhere in the Mediterranean. However, the imaginative world had been expanded by recent English voyages, notably to Bermuda and Virginia, and they therefore became the point of reference for the audience as, indeed, they remain.

The situation was less transformative as far as history was concerned. Nevertheless, Renaissance Humanism had affected peoples engagement with the past, notably in encouraging a broader-based understanding of the Classical world the ancient world of Greece and Rome and this was an important aspect of Shakespeares plot-setting as well as of his imagery and language. Authors such as Plutarch, whom Shakespeare knew through the 1579 English edition, provided guidance. Thus it was an ancient world, although not that of the Middle East, that was readily available, and led to figures such as Julius Caesar, whose character Shakespeare based closely on accounts by Plutarch, striding the boards.