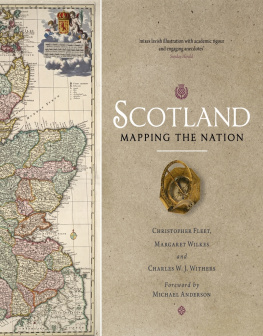

SCOTLAND:

MAPPING THE NATION

CHRISTOPHER FLEET studied Geography at the University of Durham. He is Senior Map Curator in the National Library of Scotland. In 2010, he was awarded the Fellowship of The Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

MARGARET WILKES is a Member of the Steering Committee of the Scottish Maps Forum, a Director of The Royal Scottish Geographical Society, Convenor of its Collections & Information Committee and Joint Chairman of its Edinburgh Centre.

CHARLES W.J. WITHERS is Professor of Historical Geography at the University of Edinburgh. He is a Fellow of the British Academy, the Royal Society of Edinburgh and The Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

This eBook edition published in 2013 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Christopher Fleet,

Margaret Wilkes and Charles W.J. Withers 2011

Foreword Michael Anderson 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher..

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-239-9

Print ISBN: 978-1-78027-091-3

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

FOREWORD

I have the enormous privilege of chairing the Board of Trustees of the National Library of Scotland and the pleasure here of writing a Foreword to this fascinating and beautifully produced book. Scotland: Mapping the Nation charts the development of maps and the mapping of and in Scotland over the past two millennia, describing the maps changing purposes, languages and makers. It is the work of three enthusiastexperts, self-confessedly enthralled by maps, all with huge experience of revealing the secrets of maps to users of all kinds, and it is illustrated with an amazing range of images, mostly drawn from the collections of the National Library of Scotland. Much of the content was a real revelation to me, and I know it will be also to many other readers.

As I write this in 2010, we live in a world where developments in digital mapping technology are opening up multiple new ways of presenting maps for an ever-expanding range of users. Almost weekly, we are offered new kinds of overlays, new online maps, some of which present a series of successive images to show changes over time, or offer the ability to map variables selected by the user. But the old limitations still remain: the user is restricted to those elements of the real world that the map-maker wants the map reader to see, largely within the map frameworks and range of scales that the maker has provided. Mappable information is never absolutely up to date. And, if we are to understand the result, we still need to know the symbolic conventions that are part of our own but not of other cultures: contour lines, orientation of maps with north at the top, todays colours for different kinds of roads, for example, are all comparatively recent inventions.

We can all speak from experience of working with maps. A few months ago, I was driving in broad daylight on the main road approaching the motorway outside Stirling. I did not need a map to access the motorway because I had driven this route dozens of times before. But the driver in front of me clearly did not know the road, and he was relying on his satellite navigation system to help him to understand the unknown. As he approached a new roundabout, he paused slightly as if puzzled, then followed his systems instructions and took the first exit and suddenly ground to a halt and did a rapid U-turn, as he realised he was entering the Auction Mart.

He, no doubt, cursed one perennial feature of his modern technology: it was out of date. But had he been using a similarly out-of-date Ordnance Survey map he should have noticed that he had to cross a small river, and pass a garden centre, before reaching the motorway roundabout. His focus, and that of his rolling map, was on roads; most other details were deliberately omitted. Even if there had been a blue line on his picture, he might well not have realised its significance. His experience, compared with mine, nicely illustrates, for the modern world, some of the perennial features of maps and map use that are drawn out so wonderfully in this book. It is a work to read, with reward, and to savour.

Professor Michael Anderson, OBE, MA, PhD, Dr HC, FBA, FRSE, FRHistS, Hon FFA

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Maps are everywhere. On walls; hand held; as colourful city plans designed for tourists; on our TV screens as weather forecasts and location guides; in our vehicles; bound together as atlases and used in classrooms; stored and looked at in computer and satellite devices; and, even, of course, stored in our heads as mental maps, uninscribed and almost innate ways of living in and dealing with space as we walk in our local neighbourhood or journey to work. Maps are commonplace objects, even taken-for-granted things. So are map-related metaphors: peace talks often refer to the road map for the future, for example, to charting the way forward.

Maps show the world, or portions of it. Even at a most basic level, however, maps do not straightforwardly correspond to the world, or even to the parts of it, that they purport to show. Things are missed out they have to be in order to simplify the map and make it clear to read. Those items that are included are, often, shown out of proportion again, for the ease of the map user but in ways that distort the real geography of places: motorways are shown on most travel maps as proportionally much larger than they are in reality. And because the geography of places may have changed since the map was made, maps can become out of date. Nor do maps always behave as we, the users, would want them to. J. M. Barrie, the Kirriemuir-born author best known for his Peter Pan, had clearly experienced what countless others have in working with maps when he wrote Shutting the map, part of his An Auld Licht Manse and other Sketches, in 1893. Prominent among the curses of civilisation, wrote Barrie, is the map that folds up convenient for the pocket. There are men who can do almost anything except shut a map. It is calculated that the energy wasted yearly in denouncing these maps to their face would build the Eiffel Tower in thirteen weeks. There will be few people who will not at one time or another have had their Barrie moment with a map.

All these things are true. They are the basis to the commonplace nature of maps and in one way or another they speak, like Barries heartfelt complaint, to our experience of maps today. Because maps date and places change, there is a flourishing industry in making new maps, updating road atlases on paper or as electronic data. But it is also true that these are modern questions, modern experiences born of the place of the map, paper or electronic, in contemporary society. Such issues simply do not hold for the nature of maps in the past, or for the place of maps in society at different times. Today, for example, we use the commonest types of maps, road maps and route planners, most often to navigate the route from place A to place B, thinking of the geographical distance between those places either in terms of linear distance or as time. In the past, most maps were simply not used this way. There are exceptions, of course, but in general terms route maps as guides to travel were not invented until the end of the seventeenth century.