Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

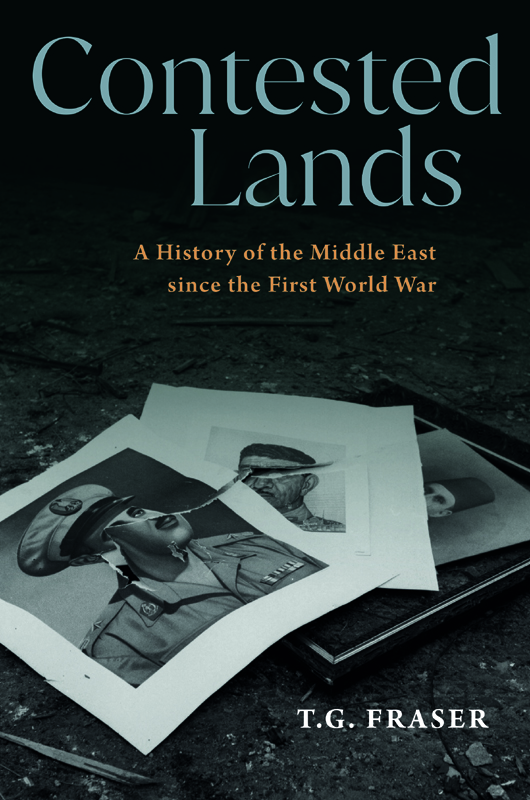

CONTESTED LANDS

Contested Lands

A History of the Middle East

since the First World War

T. G. FRASER

First published in 2021 by

Haus Publishing Ltd

4 Cinnamon Row

London SW11 3TW

Copyright T. G. Fraser, 2021

Cartography produced by ML Design and Rhys Davies

Maps contain OS data Crown copyright and database right (2020)

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

ISBN 978-1-913368-24-1

eISBN 978-1-913368-25-8

Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in the UK by TJ Books

www.hauspublishing.com

@HausPublishing

For my grandchildren,

Adam, Aidan, and Grace

1

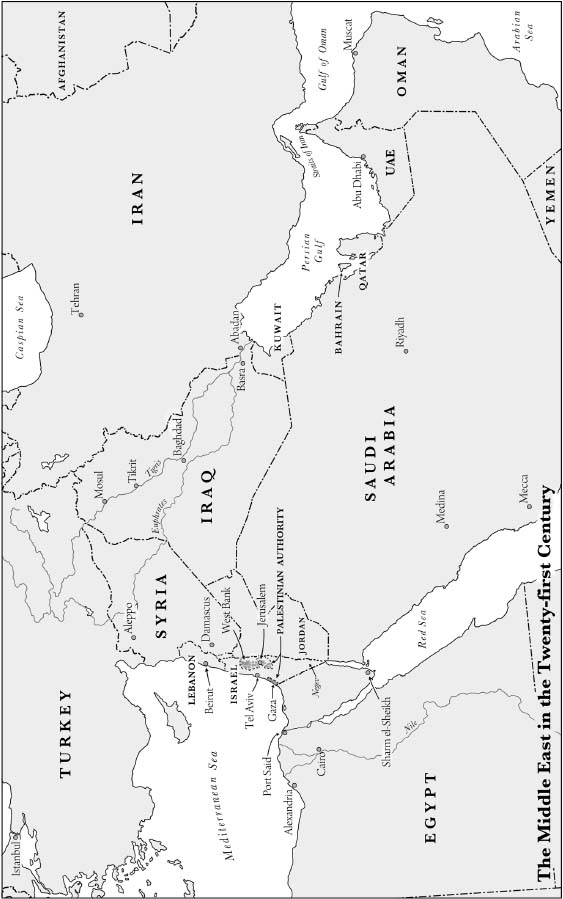

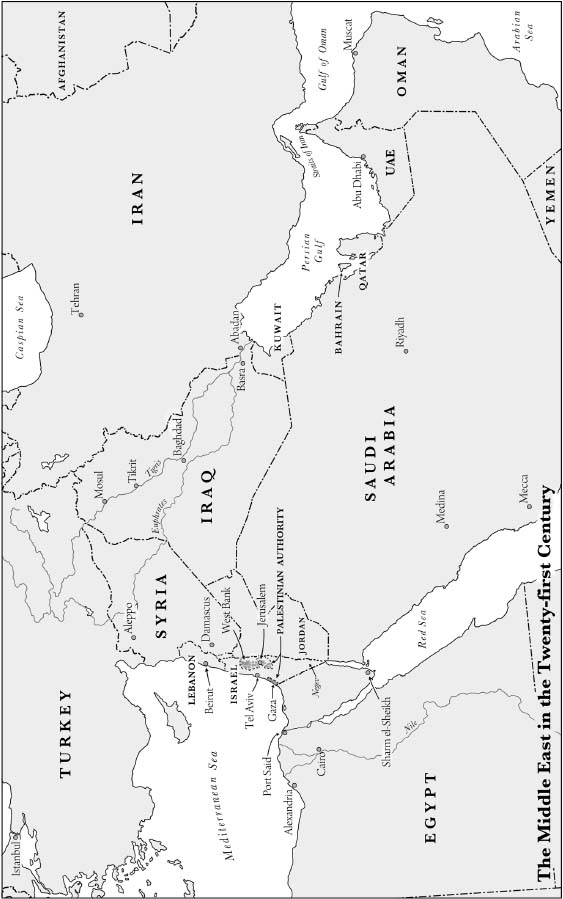

The Middle East on the Eve of War

The Middle East, as explored in this book, refers to the non-Turkish areas of the Ottoman Empire and their development in the century after the empires collapse, together with the associated polities of the Arabian Peninsula and its coastal regions. In the summer of 1914, it is doubtful whether many people would have recognised the term Middle East; if they did, they would most likely have been unsure what part of the world it described. For most Europeans, especially those British who travelled to work, colonise, or garrison their eastern possessions, the region began and ended at Port Said, the northern point of entry into the Suez Canal. The term Far East was widely used, but that hardly applied to India, the jewel in Englands crown. From the late eighteenth century, the statesmen of Europe had been preoccupied with the Eastern Question, out of which emerged the term Near East, which was used in the United States to cover a swathe of countries from Morocco to Iran. In 1905, the distinguished Oxford archaeologist and sometime intelligence officer D. G. Hogarth entitled his study of the region The Nearer East, a concept which, he argued, included the Balkans, parts of which were still ruled from Istanbul and had some claims to an Islamic and Ottoman heritage.

The region under discussion in this book possessed an enviable cultural heritage, had given rise to the worlds three great Abrahamic religions, but in political terms in 1914 was subordinate to the rule of the Ottoman Turks, as it had been for four centuries. The First World War, with the defeat of Turkey, seemed to open up new possibilities for the peoples of the region; for a period, however, any political aspirations they might have held had to contend with the imperial ambitions of the victorious British and French who were working to their own agendas. As this chapter outlines, their uni-literal actions in carving out new political boundaries in the region were to have lasting consequences even if their actual presence proved to be ephemeral.

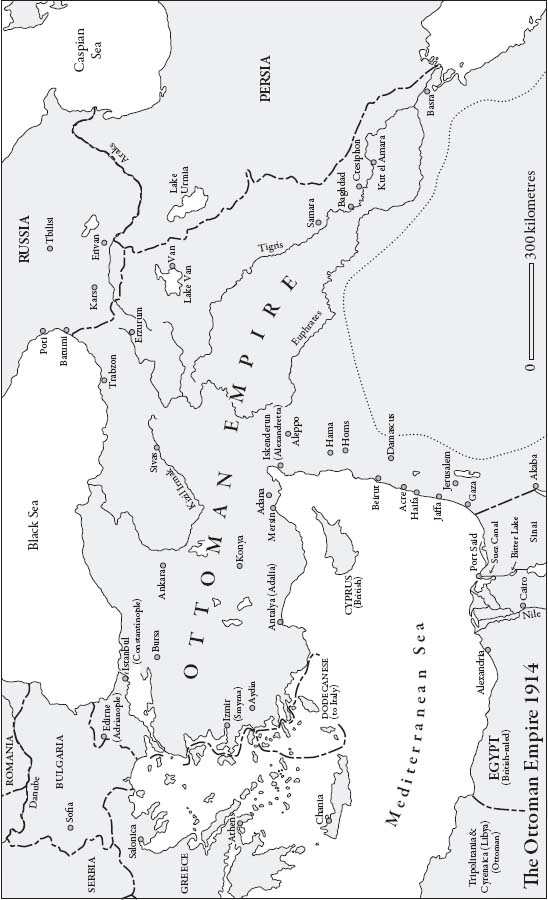

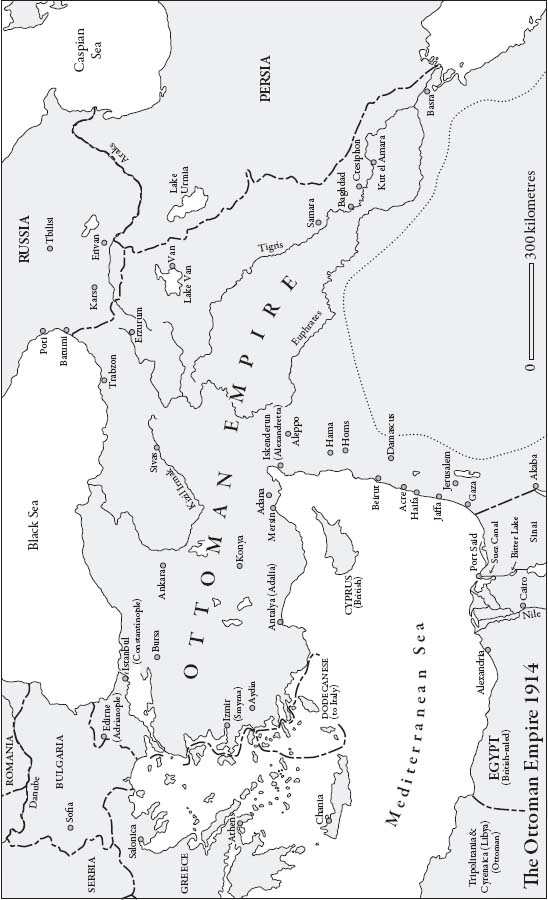

The Ottoman Empire

The term Ottoman Empire, however, was generally recognised. In addition to the Turkish heartland of Anatolia, in 1914 the Ottoman Empire ruled, or claimed suzerainty, over extensive Arab lands from its capital in Istanbul as it had done for almost exactly four centuries. Until 1909, its head had been Sultan Abdlhamid II, who ruled from 1876 until he was overthrown by those discontented with his despotism. The empire was divided into vilayets, or provinces, each under an Ottoman governor-general and sub-divided into sanjaks. Four historic Arab cities of Aleppo, Baghdad, Cairo, and Damascus belonged, however nominally, to the empire, as did the holy cities of Islam Mecca and Medina and Jerusalem, which is sacred to the three great monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It was home, too, to the two holy cities of the Shia branch of Islam: Najaf and Karbala. It was in the course of Britains war with the Ottoman Empire in these areas that the term Middle East emerged in British usage, and since the British gained post-war hegemony in much of the region, albeit transiently, the descriptor Middle East gained favour. There have long been questions of inclusion or exclusion: do the terms Near East or Middle East take in North Africa, or Crete, or Iran, or Turkey? While relations with other regional powers, notably the Turkish Republic, that emerged from the empires ruins, and Iran, as Persia became in 1935, cannot be ignored, their affairs will only be treated when they impinge on the region under discussion.

By 1914, the Ottoman Empire had been shorn of its once extensive European territories apart from a small enclave in Eastern Thrace, which enabled Istanbul to cling on as a European city, if only just. This long retreat had begun when the Turks failed in their siege of Vienna in 1683, continued as the Habsburg armies under their great general Prince Eugene expelled them from Hungary, and was completed with the rise of Balkan nationalism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For the empire, the loss of these provinces enhanced the importance of its Middle Eastern lands, not least as a source of food.

The peoples of the empire

Of an estimated population of around twenty-seven million people, if Egypt is excluded, some seven million of the Ottoman Empires inhabitants were Arabs. If anything connected the Arabs to the Turks who had conquered them in the sixteenth century, it was the fact that the sultan was also the caliph, or successor, of the Prophet Muhammad. Like the Turks, most of the Arab population belonged to the Sunni or orthodox form of Islam, this at a time when the empire seemed to be the last remaining political bulwark of the faith. This bond between rulers and ruled was less apparent among the Shia Muslim minorities, who formed much of the population in what was to become Iraq and had a significant presence in the future Lebanon and Syria. Meanwhile, the Turkish heartlands coastal regions of Anatolia were home to a large and thriving Greek Christian population. In the countrys interior were the Christian Armenians and Sunni Muslim Kurds. The latter formed one of the largest minority communities in the empire, although their numbers were hard to judge since many were nomadic and they also had a substantial presence in Persia and, to a lesser extent, in Russia. Their post-war hopes for a Kurdish homeland were to be confounded.

Christians of various denominations could be found throughout the empire with some important enclaves, notably the Maronites around Mount Lebanon. The Maronites are a distinctive community. They have their own patriarch and rituals but also recognise the papacy and are in communion with the Roman Catholic Church. Maronite clergy were educated either in Rome or at the seminary of Saint-Sulpice in Paris, the latter reflecting their long-standing cultural links with France. There were also ancient Jewish communities,

The economy

The regions population was united by their use of the Arabic language. Not only was it the language of the Holy Quran but it had long succeeded in supplanting its rivals as the means of universal communication. This was essentially a pre-industrial society in a region whose arid nature meant cultivable land was at a premium and fresh water was a precious commodity. The bedrock of the economy was subsistence agriculture, with the settled fellahin (peasants) growing wheat and barley, which had been the staples of life for millennia, in the winter and rice and millet in the summer. In addition to these customary staples, the region was famous for its olives and dates. Pastoral farming was almost entirely dependent on sheep and goats, equally prized for their meat, milk, and coats, and neither of which relied on abundant, lush pasture. The horse was a symbol of high social status, but it was the donkey that was used for travel and ploughing, while in the great desert areas, home to the nomadic Bedouin, all rested on the unique qualities of the camel. The Arab peasant farmers were passionately attached to their land but often their title to it was uncertain, little being owned outright. Much of it was common land, based on the