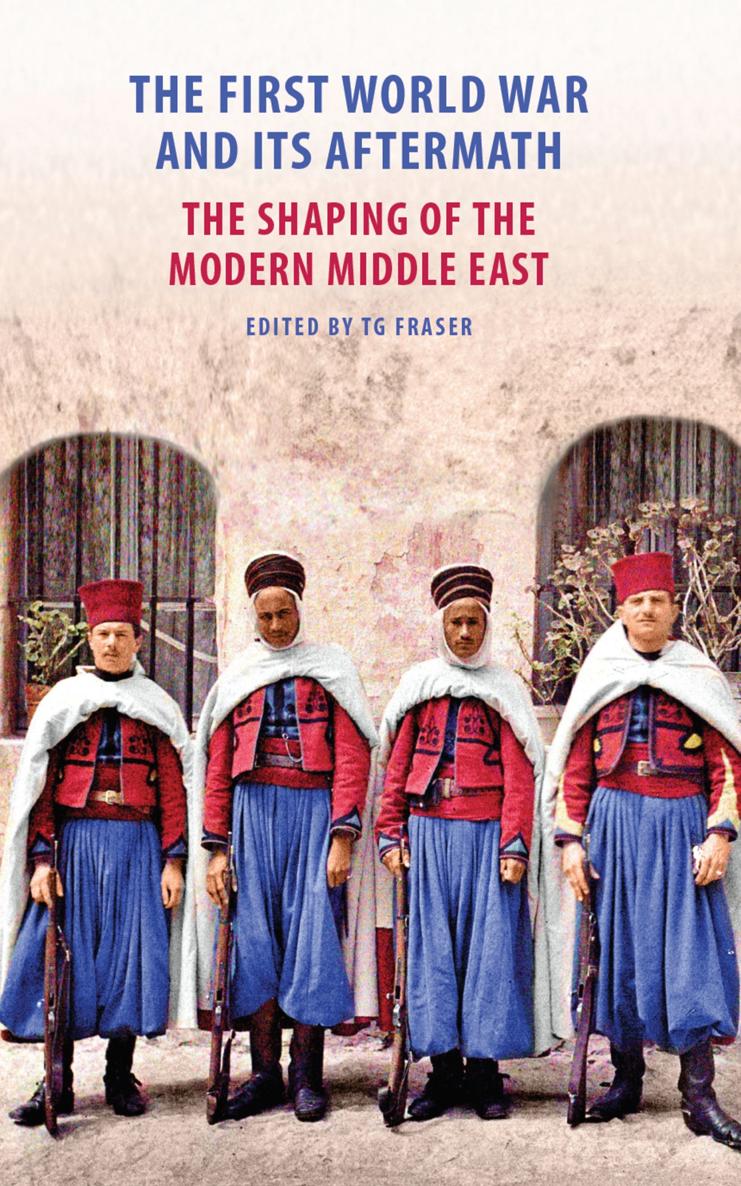

The First World War and its Aftermath

The Shaping of the Middle East

Edited by T. G. Fraser

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Gingko Library

70 Cadogan Place

London SW1X 9AH

Copyright 2015 individual chapters, the contributors

The rights of the contributors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

ISBN 978 1 909942 752

eISBN 978 1 909942 769

Typeset in Optima by MacGuru Ltd

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

www.gingkolibrary.com

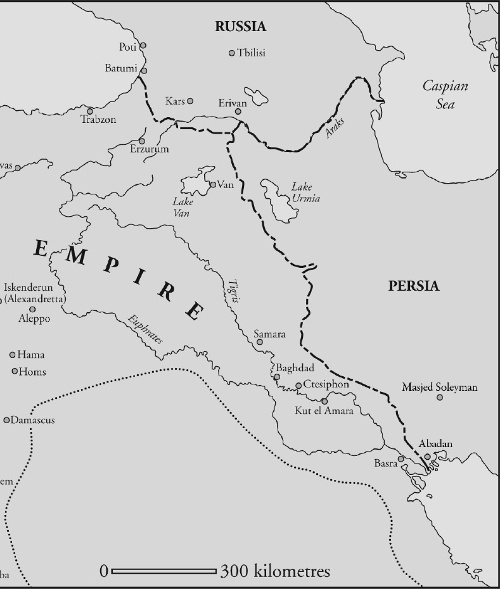

Introduction: the political transformation of the Middle East 19141923

T.G. Fraser 1

The political map of the Middle East in 1923 could not have been more different to what it had been ten years before. Through no wish of their own most of the peoples of the region were under the rule of Britain and France. There were three exceptions to this. Under the commanding hand of Mustafa Kemal the Turks were emerging from the wreckage of their empire to forge a new national identity in their Anatolian heartland and the Egyptians, who had rebelled against British tutelage in 1919, had been granted sovereignty in 1922, albeit as yet limited. In the Arabian peninsula after a series of military successes against his rivals, Ibn Saud was poised to take over the Hijaz. Otherwise, the areas which had formed part of the Ottoman Empire were part of an Anglo-French imperium, disguised as Mandates from the newly-formed League of Nations. What had brought about this transformation of the Middle East had, of course, been the First World War, the defeat of the Ottomans, and the attempts at a peace settlement which followed. Of the victorious Allied and Associated Powers, the United States, which had never been at war with Turkey, showed no inclination to become directly involved in the region, neither did the Japanese whose focus was elsewhere, while the Italians and Greeks tried but failed. With their overwhelming military strength, that left the leaders of Britain and France free to dispose of the Middle East as they saw fit, or so they thought.

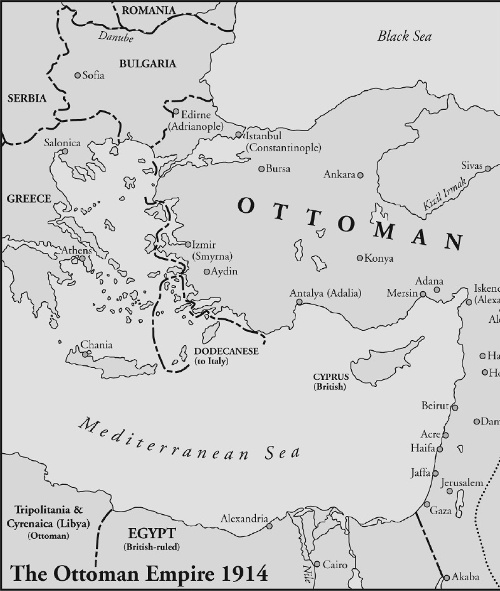

The Ottoman Empire on the eve of war in 1914 presented many paradoxes, prime amongst which were its prospects of survival. From the time of the capture in 1453 of Constantinople, the last faint echo of the Roman Empire, the Ottoman Turks had created an empire which at its zenith embraced territories and peoples across three continents. It was only with their failure at the siege of Vienna in 1683 that the remorseless advances of Prince Eugenes Habsburg armies pushed the Ottomans farther and farther into the Balkans, so that by 1914 the capital of Istanbul seemed uneasily positioned close to the new states of south-eastern Europe which had emerged in the course of the 19th century. Together with the atrophy of their position in Europe went the erosion of their rule in North Africa. From 1882 Egypt was de facto ruled by the British who were concerned to safeguard their vital imperial life line of the Suez Canal. While the country was still under the suzerainty of the Sultan in Istanbul, this fiction was ignored by the British who brooked no challenge to their rule. In 1911, the remaining Turkish possessions in North Africa, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, were seized by Italy.

By 1914, then, the Ottoman Empire had become in real terms a Middle Eastern polity, but it must not be thought that this was necessarily a position of weakness, still less that it was facing the prospect of final collapse and dissolution. There was a secret organisation, mostly composed of young army officers schooled in fighting in the Balkans, who were determined to restore the empires fortunes. Known as the Committee of Union and Progress, or Young Turks, they secured a form of constitutional rule in 1908, ousted the autocratic Sultan Abdul Hamid II the following year, and in 1913 mounted a coup detat. Led by two army officers, Enver and Cemal, and a civilian, Talat, they sought to reverse the empires record of military defeat, turning to the Germans to reorganise the army, while entrusting the navy to the British and the paramilitary gendarmerie to the French. Although the armys equipment and infrastructure generally could not match the standard of the major European powers, it was equipped with modern Mauser repeating rifles and 198 batteries of Krupp artillery. Above all, the courage and toughness of its soldiers were of a high order, as the British imperial forces were to find out. But the military reforms had barely got under way when the army had to face a war against three of the leading armed powers of Europe and in the resulting conflict the empire was to be tested beyond its limit.2

Of the empires estimated population of some 26,000,000, 10,000,000 were Turks and 7,000,000 were Arabs, mostly Sunni Muslims. What united Sunni Turks and Arabs was their common allegiance to the Sultan as Caliph of Islam, although sections of the latter would have preferred an Arab Caliph. More marginalised were the Shia Arabs of the Tigris and Euphrates and the large Christian minorities, most obviously the Armenians whose aspirations found an echo across the Russian border, with tragic consequences for them in 1915 once the two empires clashed. Long-standing Jewish communities existed in their Holy Cities of Jerusalem, Safed, Tiberias and Hebron, but also in Baghdad and Mosul. There were, in addition, the Zionist settlements in Palestine which had grown up in the wake of anti-Jewish persecutions in Russia from the 1880s and the formation of the Zionist organisation by the Austro-Hungarian journalist Theodore Herzl in 1897. Other minorities were the Greeks, with their ancient settlements along the Aegean coasts, the Kurds, Maronites, Copts, Alawites, Druzes, Yezidis, Circassians and Chaldeans. Cosmopolitan Istanbul was a microcosm of the empire as a whole.