Worthy

Opponents

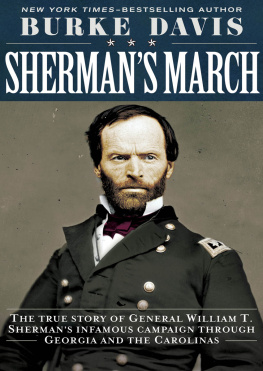

GENERAL WILLIAM T. SHERMAN, U.S.A.

GENERAL JOSEPH E. JOHNSTON, C.S.A.

Edward G. Longacre

Rutledge Hill Press

Nashville, Tennessee

A Division of Thomas Nelson Publishers

www.ThomasNelson.com

In memory of my cousin, Ellen Ewing Sherman

Copyright 2006 by Edward G. Longacre

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Rutledge Hill Press, a division of Thomas Nelson, Inc., P.O. Box 141000, Nashville, Tennessee 37214.

Rutledge Hill Press books may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund-raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail SpecialMarkets@ThomasNelson.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Longacre, Edward G., 1946

Worthy opponents : William T. Sherman and Joseph E. Johnston : antagonists in warfriends in peace / Edward G. Longacre.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 973-1-4016-0091-4 (harcover)

ISBN-10: 1-4016-0091-3 (hardcover)

1. Sherman, William T. (William Tecumseh), 1820-1891. 2. Johnston, Joseph E. (Joseph Eggleston), 1807-1891. 3. GeneralsUnited StatesBiography. 4. United States. ArmyBiography. 5. GeneralsConfederate States of AmericaBiography. 6. Confederate States of America. ArmyBiography. 7. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865Campaigns. I. Title.

E467 .L22 2006

973.7'30922dc22

[B]

2006021518

Printed in the United States of America

06 07 08 09 105 4 3 2 1

Table

of Contents

One: The School of the Soldier

T his book chronicles in parallel form the lives of two American soldiers, bitter rivals in wartime, who became fast friends once the guns ceased firing. For four years beginning in April 1861, Joseph Eggleston Johnston, C.S.A., and William Tecumseh Sherman, U.S.A., waged war against each others army and nation, although not always in the same theater of operations. At intervals from May 1863 to July 1864 and again from February through April 1865a period that encompassed some of the most celebrated engagements in the history of warfarethey directly confronted each other on the field of battle. During that time, while striving by every resource and stratagem to outwit, outmaneuver, and defeat each other, each developed a genuine respect for the intelligence and determination of his opponent.

Their mutual admiration increased after they came face to face to negotiate the surrender of Johnstons Army of Tennessee near Durham Station, North Carolina, at the close of the war in the West. In after years, although they led very different lives, their paths crossed with such frequency that they came to know each other in an entirely new context. They grew especially close in the 1880s, when both resided in Washington, Sherman as the commanding general of the United States Army and Johnston as a congressman from Virginia and then as United States commissioner of railroads, a position Sherman helped him gain and hold onto. They and their families dined, entertained, and traveled together, and whenever alone the two old soldiers good-naturedly refought the campaigns that had made their reputations. Johnston readily acknowledged that he spent more time with his former enemy than he did with the veterans of his own army. One of Shermans subordinates, Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, observed that for the last twenty years or so of their lives, the old antagonists behaved always toward each other as brothers.

On the surface, the two men were a study in contrasts. The compact, dignified, gentlemanly Johnston was thirteen years older than the gangly, garrulous, nervous Ohioan. Their regional influences, political views, and military experiences differed markedly. Yet they shared a number of personal and professional traits. As the sons of judges, from youth they evinced a deep interest in, and an abiding reverence for, the laws of the land, especially the United States Constitution, although differing in their interpretation of key provisions of that seminal document. Both espoused a conservative outlook on socio-economic issues, including slavery, an institution that each deplored but tolerated due to deep-seated doubts that a race long held in bondage could meet the full requisites of citizenship. Each had a high regard for personal honor and reacted strongly to perceived attacks on his name and reputation.

Their conservatism colored their military tactics. Both appreciated the inherent advantages of an entrenched army fighting on the defensive. When committed to the offensive, each preferred the indirect approach, relying heavily on feints, flanking maneuvers, and threats to lines of communication and supply as a means of drawing the opponent out of his field works and into the open, where he would be isolated and vulnerable. Each was concerned with husbanding and concentrating his strength so as to bring maximum power to bear against critical sectors of the enemys position. Each took pains to avoid exposing his armys flanks and rear so as not to create an opening the other might exploit. During most of their confrontations, circumstances required Sherman to take the offensive, Johnston to maintain the defensive. Throughout, however, each maneuvered carefully, cautiously, aware that a false move might bring disaster. Occasionally, both felt compelled to take risks as Sherman did at Kennesaw Mountain during the Atlanta campaign and Johnston resorted to at Bentonville during the campaign of the Carolinas. Such instances, however, were rare, mainly because they proved costly. For the most part, each was too wary of the exploitative powers of his adversary to tempt fate or act precipitately.

Sherman went on record with the observation that Johnston was the shrewdest, cleverest opponent he ever faced. Thus he described Johnstons relief from command in mid-July 1864 as the greatest gift the Confederacy could have given him. For his part, Johnston admitted that Sherman was too savvy and vigilant to be drawn into a confrontation on terms even slightly advantageous to the Army of Tennessee. His greatest regret was Shermans refusal during the 1864 campaign in Georgia to behave as his friend and superior, Ulysses S. Grant, did toward Grants opponent in Virginia, Robert E. Lee. Had Sherman attacked him directly and repeatedly, Johnston argued, the Army of Tennessee would have emerged victorious from this, perhaps the most fateful epoch of the war. Yet Shermans unwillingness to act as Johnston wished him to only increased the latters admiration of the former.

It seems fitting that Shermans and Johnstons mutual respect evolved into true friendship, for that progression mirrored the course of reunion and reconciliation during the latter years of the nineteenth century. Divided in war, united in peace, their relationship was, on an intensely personal level, the story of their battered and bloodied but durable and resilient nation.

In the course of preparing this book, several institutions provided research assistance; to them I am deeply indebted. Those most deserving of mention include the reference and special collections staffs of the Ohio Historical Society, the University of Notre Dame Libraries, Duke Universitys William R. Perkins Library, the Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the William L. Clements Library of the University of Michigan.

Next page