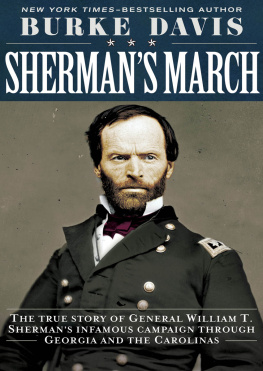

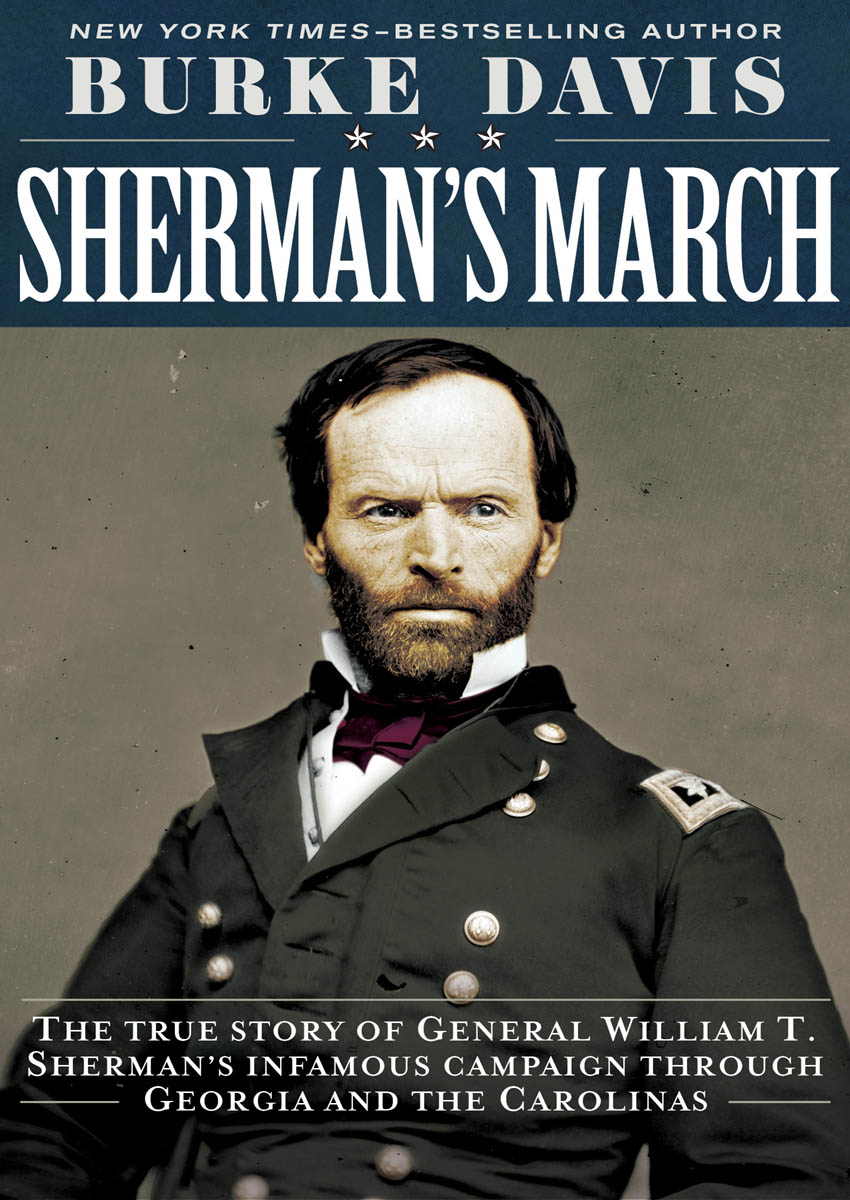

Shermans March

Burke Davis

To Archie and Wayne

and the faculty of the New River War College

Contents

He believes in hard war

From a window of a brick house on the hill a bearded face peered across the burning heart of Atlanta. It was a face incredibly wrinkled and furrowed, dominated by a ruddy scimitar of a nose and a broad mouth that writhed about the stump of a cigar as the tall man spoke to those in the room behind him.

General William T. Sherman glanced restlessly about, squinting toward a setting sun now obscured by smoke, to the courthouse and Masonic hall, still undamaged, into an inferno of blazing railroad shops, depots and factories, and along streets patrolled by Federal sentries who were under Shermans orders to save churches and private homes.

Scorching heat pulsed against the columned mansion where Sherman made his headquarters, and in the growing darkness the glare lighted the countryside so brightly that soldiers in camps a mile from the city could read their letters from home. Exploding shells burst in the ruins of captured Confederate arsenals, shaking the house and rattling shrapnel against its walls.

It was November 15, 1864. Shermans troops, some 62,000 strong, had already begun to evacuate the burning city. By the next morning they would be off on a thousand-mile foray through the heart of the reeling Confederacy that would leave a path of destruction eighty miles wide, pillage three state capitals, and bring an end to the war that had racked the nation for three years.

The general rubbed the thinning thatch of his hair upward with both hands, tugged at his blouse buttons, drummed the window sill with his fingers, seized the cigar, snapped furiously at its ashes and replaced it, puffing in a fury, shooting smoke from his mouth like pistol fire, as if it were the last cigar in the world. His soldiers had often seen him in such a state, picking nervously at himself with fluttering fingers. One of them said, I never saw him but I thought of Lazarus.

The city that he had so recently captured seemed to Sherman a symbol of Confederate resistance. Atlanta, he said abruptly. Ive been fighting Atlanta all this time. Its done more to keep up the war than anywell, Richmond, perhaps. All the guns and wagons weve captured along the wayall marked Atlanta. He was determined that the city would no longer serve as a major Confederate supply center. He had captured Atlanta on September 2, after one of the wars most brilliant campaigns, and six weeks later was now to leave it behind, ungarrisoned, to lead his troops on a march that was to bring him military immortality.

Sherman turned into the room, gesturing to his officers with his cigar-stump baton. Theyve done so much to destroy us, weve got to destroy Atlantaat least, enough to stop any more of that.

No one, not even the most devoted of his staff, could imagine that Sherman was on the threshold of fame tonight. He strode to the dining table and sank into a mahogany chair as awkwardly as if he were straddling a cracker box, his customary seat in the field. Sherman was a slight, almost frail figure of deceptively wiry strength.

He wore no badge of rank. His weather-stained blouse looked as if he had slept in it for three years of war; he wore a dirty dickey with wilted points, a faded gray flannel shirt, muddy brown trousers older than the memory of his most veteran staff officer, low-cut shoes rather than boots, and but one spurthe only general of either army who affected shoes and a single spur.

Shermans headquarters would have done justice to a bandit chief. It traveled in a single wagon, including baggage for all clerks, aides and orderlies. I think its as low down as we can get, he said. He scorned elaborate equipment hauled along by comfort-seeking officers as a farcenothing but poverty will cure it. There had been only three aides, though two others had come recently, one of them Major Henry Hitchcock, a young Republican lawyer from St. Louis who was assigned to handle a correspondence that had begun to overwhelm the general: Just tell em something sweet, Hitchcockyou know, honey and molasses.

Hitchcock had been completely won over by Sherman at their first meeting. Despite the generals eccentricities, the young lawyer found him straight-forward, simple, kind-hearted, nay, warmhearted scrupulously just and careful of the rights of others. Above all, Hitchcock was impressed with Shermans competence: You may be sure of one thingwhat he says he can do, he can.

Tonight the generals meal was as simple as those of his interminable marcheshardtack, sweet potatoes, bacon and coffee. Sherman gnawed at a flinty piece of hardtack and began his familiar lecture on its virtues, halted to greet a dispatch-bearer, ripped open a message and barked out a reply. He talked of the enemy, of Southern women, of U. S. Grant and President Lincoln, heedlessly gulping his food, then returning to the smoldering cigar, still talking and laughing, giving orders, dictating telegrams, bright and chipper, one of his generals noted. He cut short others who spoke and went on with his hurried comments, refusing to be interrupted. Im too red-haired to be patient, he had said. A war correspondent described him as he was at this moment: He walked, talked or laughed all over. He perspired thought at every pore pleasant and affable engaging with a mood that shifted like a barometer in a tropic sea.

The meal was ended by a regimental band from Massachusetts blaring beneath the windows in a serenade to the general, the brasses pealing incongruously above the explosions and roaring flames. Sherman listened briefly, lost interest and turned back to dispatch-bearers and officers who had come for orders. After a few lively military tunes the band played the Miserere from Il Trovatore, whose melancholy beauty, Henry Hitchcock thought, would forever remind him of this November night of roaring flames when Atlanta was destroyed and the army began its march to the sea.

Drunken Federal soldiers had been setting fires in the stricken city for several days, in defiance of Shermans orders, but the official work of destruction had begun only when two Michigan regiments knocked down the massive stone roundhouse with improvised battering rams, placed powder charges under large buildings, and piled mountains of worn-out wagons, tents and bedding in the railroad depot, ready for the torch.

Sherman had ordered the citys destruction postponed until this night of November 15. A foundry, an oil refinery and a freight warehouse were burned first; the blazing depot square spread a storm of fire. The Atlanta Hotel, Washington Hall, dry-goods stores, theaters, the fire stations and jail, slave markets, went up in flames. A mine exploded in a stone warehouse. Old pine timbers burned with astonishing brilliance and flung brands in all directions. The sun shone blood red through a thickening cloud. The air for miles about was oppressive and intolerable.

By night the burning city was the grandest and most awful scene, with fires towering hundreds of feet into the sky. Hitchcock watched in fascination: First bursts of smoke, dense, black volumes, then tongues of flame, then huge waves of fire roll up into the sky: Presently the skeletons of great warehouses stand out in relief against sheets of roaring, blazing, furious flames as one fire sinks, another rises lurid, angry, dreadful to look upon.