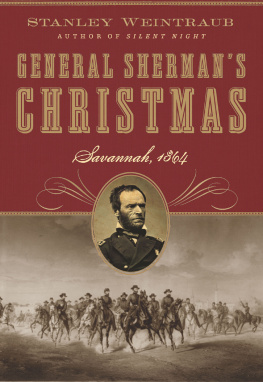

Savannah, Georgia, December 22, 1864

To His Excellency President Lincoln, Washington, D.C.

I beg to present you as a Christmas-gift the city of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty heavy guns and plenty of ammunition, also about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton .

W. T. Sherman ,

Major-General

My Dear General Sherman ,

Many, many thanks for your Christmas giftthe capture of Savannah .

When you were about to leave Atlanta for the Atlantic coast, I was anxious , if not fearful; but feeling that you were the better judge, and remembering that nothing risked nothing gained, I did not interfere. Now, the undertaking being a success, the honor is all yours .

Yours very truly ,

A. Lincoln

Unplanned and improvised, General Shermans telegram offering President Lincoln Savannah for Christmas has been part of Civil War lore since Christmas Day in 1864. Yet much of the actuality of the event has slipped past history. How did the siege and capture happen? What was it really like, then and there? What hasnt, until now, been told? How much likely fiction in the multiplicity of accounts needs to be excised? The widely popular song of the year after, the jaunty Marching Through Georgia, although boastfully accurate but for a single stanza, curiously opens with a misleading line in its first verse, and, even before that, a mistake:

Bring the good old bugle, boys, well sing another song .

Sing it with a spirit that will start the world along.

Sing it as we used to sing it, 50,000 strong ,

While we were marching through Georgia .

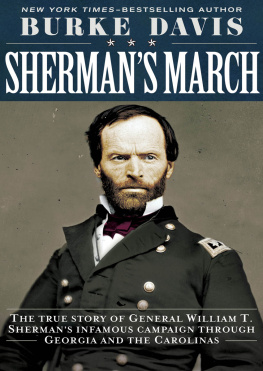

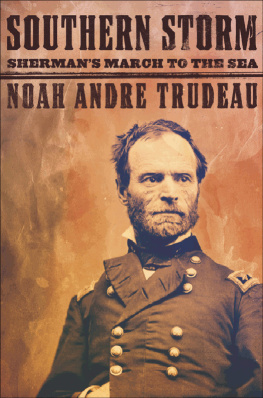

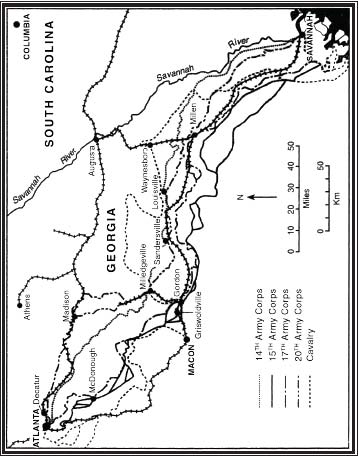

No one sang the ballad while marching through Georgia. Although brass bands pumped Blue Juniata and the melancholy When This Cruel War Is Over to the patriotic Rally Round the Flag and the realistic Tenting Tonight, Henry Clay Work, ironically named for a Southern senator, composed Marching Through Georgia the year after. Further, the soldier in the verse recalling the march would have known that General William Tecumseh Shermans four army corps and independent cavalry brigade comprised over sixtyrather than fiftythousand infantrymen and light artillery supported by several thousand horsemen.

Wreaking deliberate ruin, the three-hundred-mile march, familiar from many accounts, was a countrywide dose of noxious but needed medicine in a time of deadly plague. The civil war had been initiated in misguided idealism by Southerners claiming the right to detach their states from a union they felt was undermining lawful property rights to human beings. Northerners insisted that the federal union, once entered into, was indissoluble; and to keep it so, the war had become as inglorious as it was long. In its fourth year the idealism had vanished. Except for die-hards, the glorious Cause in the South was reduced to survival. The North had already paid a very high price for continuity. Although an attractive peace-and-compromise candidate was challenging President Lincolns bid for reelection, the question was whether the disillusioned Union would settle for anything less than outright victory.

Unknown, little-known, and long-silent voicesfrom a semiliterate Illinois private and an unlettered Alabama farmer and his wife, to immigrant soldiers loyal to both North and South, and the nearly forgotten presidents son who became a Rebel generalenrich this account of an episode that has belonged to myth as much as to history. However crucial, little significance has been given to the impact of Lincolns once-doubtful reelection campaign, the first in which soldiers in the field cast ballots, upon whether the march from Atlanta would begin or would be aborted. Christmas in Savannah in 1864, and the future of the Union, might both have been very different had the bayonet election gone the other way.

Just before the drive to the sea began, a Georgia clergyman innocent of wartime wrongdoing penned a protest to Sherman that a horse to which he had title had been stolen by a Federal rifleman near Atlanta. Since looting and burning by both sides were the inevitable byproducts of war, Sherman deplored the theft but cautioned that the great board of claims in Washington would be useless in their lifetimes, or even by the time your grand-child becomes a great grandfather. He had no immediate remedy. Privately, I think it was a shabby thing in the scamp of the 31st Missouri who took your horse. Still, Sherman assured the clergyman that he could not repair the sins of the horse thiefs superiors, although they were his own subordinates, even up to the brigadier level. When this cruel war is over, he wrote, echoing a wistful song sung by both sides, and peace once more gives you a parish, I will promise, if near you, to procure out of one of Uncle Sams corrals a beast that will replace the one taken from you so wrongfully, but now it is impossible. We have a big journey before us and need all we have, and, I fear, more too; so look out when the Yanks are about and hide your beasts, for my experience is that all soldiers are very careless in a search for title. I know that Gen. Hardee will confirm this, my advice.

William Hardee, the shrewd Georgia general whom Sherman would confront in Savannah, was also a realist about war, Sherman implied; yet the implacable Hardee, consumed by the Cause, would continue to fight a war already well lost. Shermans big journey into the last Christmas of the war follows.

M IDNINETEENTH CENTURY WRITERS often capitalized words at random, and spelled with dismaying inaccuracy and inconsistency. Between quotation marks such variations are let stand. Among oft-used nouns (sometimes used as adjectives) both capitalized or left otherwise, and spelled in a variety of ways in singular and plural uses, are Negro/negro and Black/ black. Again, these are printed as recorded, within quotations. Military ranks altered, usually upward, during the war. Often a writer will refer to a person by a later rank. These remain as written. Spoken dialogue, even from participants, often differs in details. Since memory sometimes slips, primacy is given to the person writing closest to the events. Proper names are sometimes at odds in different accounts. Here, later research is awarded primacy over recollection.

Stanley Weintraub

Beech Hill

Newark, Delaware

F EW IN THE EMBATTLED U NION STATES EARLY in 1864 had Savannah on their minds. Rather, they wondered whether Abraham Lincoln should be nominated for a second term, let alone keep the White House. In the South, however, the Savannah News confidently expected to see the North torn by internecine feuds, and utterly demoralized in the Presidential election. The results augured otherwise.

By Thanksgiving Day, November 24, newspapers from Confederate Richmond picked up in occupied towns and railway stations offered complete results of what was being described, because of its unique military dimension, as the bayonet vote. Via the Rebel press, the news reached Major General William Tecumseh Shermans troops pushing across Georgia toward Savannah. Preliminary tallies, including balloting by troops in the field, had been wired down soon after the polls closed. Unwilling to open what might be an aborted campaign if the opposition candidate had won, Sherman had awaited the certainty of Lincolns reelection before ordering telegraph wires severed to insulate his army from both North and South.