1981, 1999 by John F. Marszalek

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 98-13764

ISBN 0-87338-619-1 (pbk.)

Manufactured in the United States of America

Revised edition

First edition published by Memphis State University Press, 1981.

05 04 03 02 01 00 99 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Marszalek, John F, 1939

Shermans other war: the general and the Civil War press / John F. Marszalek. Rev. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-87338-619-1 (alk. paper)

1. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Journalists. 2. Sherman, William T. (William Tecumseh), 18201891Relations with journalists. 3. Freedom of the pressUnited StatesHistory19th century. 4. JournalistsUnited StatesHistory19th century. I. Title.

E609.M37 1998

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

It has been over fifteen years since the first edition of this book appeared. At that time, in 1981, the nation was still grappling with the immediate implications of the Vietnam War and the trauma of the resignation of President Richard M. Nixon. Print and television media had played an important role in both cataclysmic events; a significant number of Americans blamed or credited correspondents with getting the nation out of the Asian War or losing it, unfairly bringing down a president or ridding the nation of a menace to the constitution.

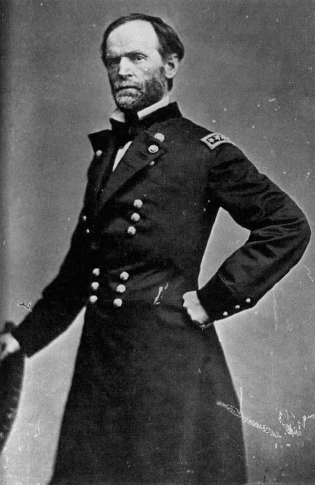

A book detailing the anti-press activities of a major American military leader in the nineteenth century, therefore, seemed timely in those turbulent days. William T. Shermans battle with Civil War reporters resonated at a time when Richard Nixon and his vice president, Spiro T. Agnew, railed against the media, and military figures, both famous and in the trenches, blamed the press for the loss in Vietnam.

As was the case in the 1970s, the political-military-media battle during the Civil War seemed to focus on the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. What did the Founding Fathers mean when they guaranteed freedom of the press in the Bill of Rights? Were press rights the same in wartime as they were in peace? How far could leading politicians and military leaders go in defending their positions on the issue? Where did defense of the constitution or of national security begin and end?

In the years since 1981, the issue of the media in time of war has been argued and reargued several times. President Ronald Reagan invaded Grenada in 1983 and launched air strikes against Libya in 1985. President George Bush sent troops into Panama in 1989, the Persian Gulf in 1991, and Somalia in 1992. President William Clinton maintained troops in Somalia and placed military units in Haiti and Bosnia. In all these cases there was no declaration of war, but the American military faced combat anyway and worked to control reporters, actually to eliminate them from the battlefield. Meanwhile, the federal courts dealt with suits that unsuccessfully sought judicial resolution of the problem.

The actions of these late-twentieth-century presidents, therefore, have shown that the issue of press freedom within the context of the protection of national security has not yet been resolved. If anything, the issue has become even more problematic than before. The national government has asserted and assumed definitive control over the media in several modern wartime situations, determining that it has the power and authority to exclude reporters completely and give the American public its own perception of events. The military has clearly gained the upper hand over correspondents on the battlefield.

Once again, therefore, and even more than was the case in 1981, a book that discusses the anti-press activities of a leading Civil War general has lessons for modern times. William T. Shermans war against reporters and their battle with him are concrete demonstrations of the issues that continue to dog modern Americans at war, even to the end of the twentieth century.

The central figure of this study, William T. Sherman, spent a great deal of time and energy pondering and acting on this question. His anti-press views stand out more than anyone elses in American military history because of his conclusion that there was a direct relationship between press censorship and military victory. He was never satisfied with the disjointed government censorship activity during the Civil War, so he diligently and consistently tried to implement his own more severe anti-press ideas. He fought a war with newspaper reporters at the same time he was fighting the Confederacy. His actions provide insight into the motives and thoughts of similar anti-press public figures at other times in American history.

Civil War newspapers and their correspondents were equally determined to protect what they considered to be their constitutional guarantees. They battled government restrictions and those military men who tried to enforce them. Since Shermans anti-press activities were so blatant, he was a constant target of intense newspaper counterfire. As a result, two determined forces (Sherman and the press) vied for the victory each saw as central to its causes success. Their war within a war exemplified the difficulties inherent in the universal problem of freedom of the press within a democracy at war.

It might seem that the Sherman-press Civil War battle was the result of a difference in constitutional interpretation. Sherman believed that the press should have no rights during war. Reporters, on the other hand, maintained that their rights were no different in war than they were in peace. Winning the war took precedence over the Bill of Rights, said Sherman; maintain the Bill of Rights over and above everything else, said the newspapers. The inevitability of conflict was obvious, given these two views.

Actually, as this book will attempt to show, neither Sherman nor the Civil War correspondents developed a consistent constitutional philosophy. Their battle was more a personal conflict than a constitutional debate, and, for this reason, it has historical relevance. Given the fact that, historically, press control in wartime has been less a constitutional than an ad hoc reaction to the immediate circumstances, and given the fact that such is still the situation, a study of American historys leading anti-press military man continues to have obvious significance for the present and the future.