A Christmas Far from Home

A Christmas Far from Home

An Epic Tale of Courage and Survival during the Korean War

Stanley Weintraub

Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

Copyright 2014 by Stanley Weintraub

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address Da Capo Press, 44 Farnsworth Street, Third Floor, Boston, MA 02210.

Designed by Jack Lenzo

Set in 12 point Caslon by The Perseus Books Group

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-0-306-82233-9 (e-book)

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

www.dacapopress.com

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special.markets@perseusbooks.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Phil Zimmer, whose suggestions originated this book

The second law of thermodynamics dictates that every physical system tends toward maximum disorder.

Contents

Escape into Fantasy

Gimee tomorrow.

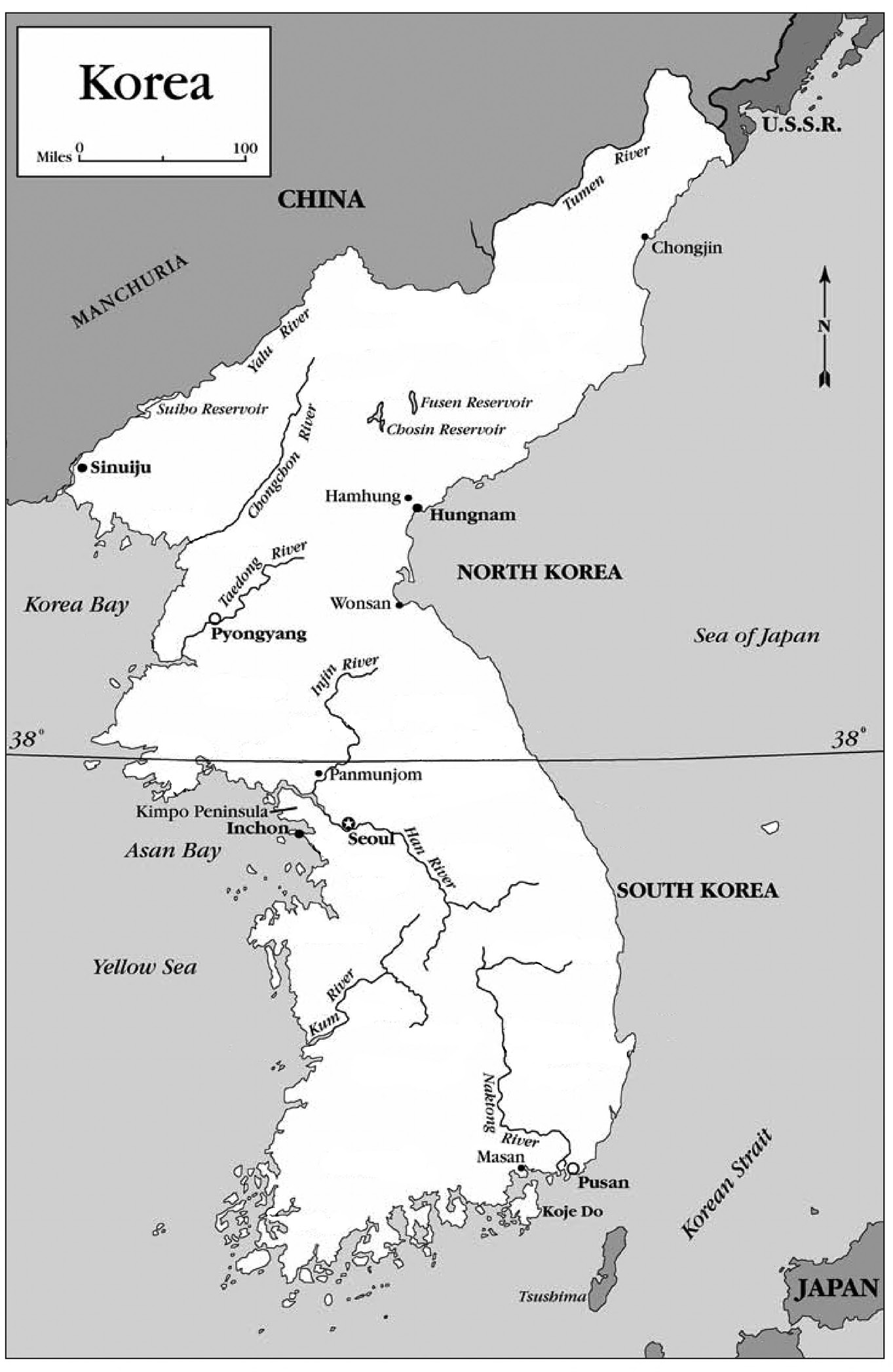

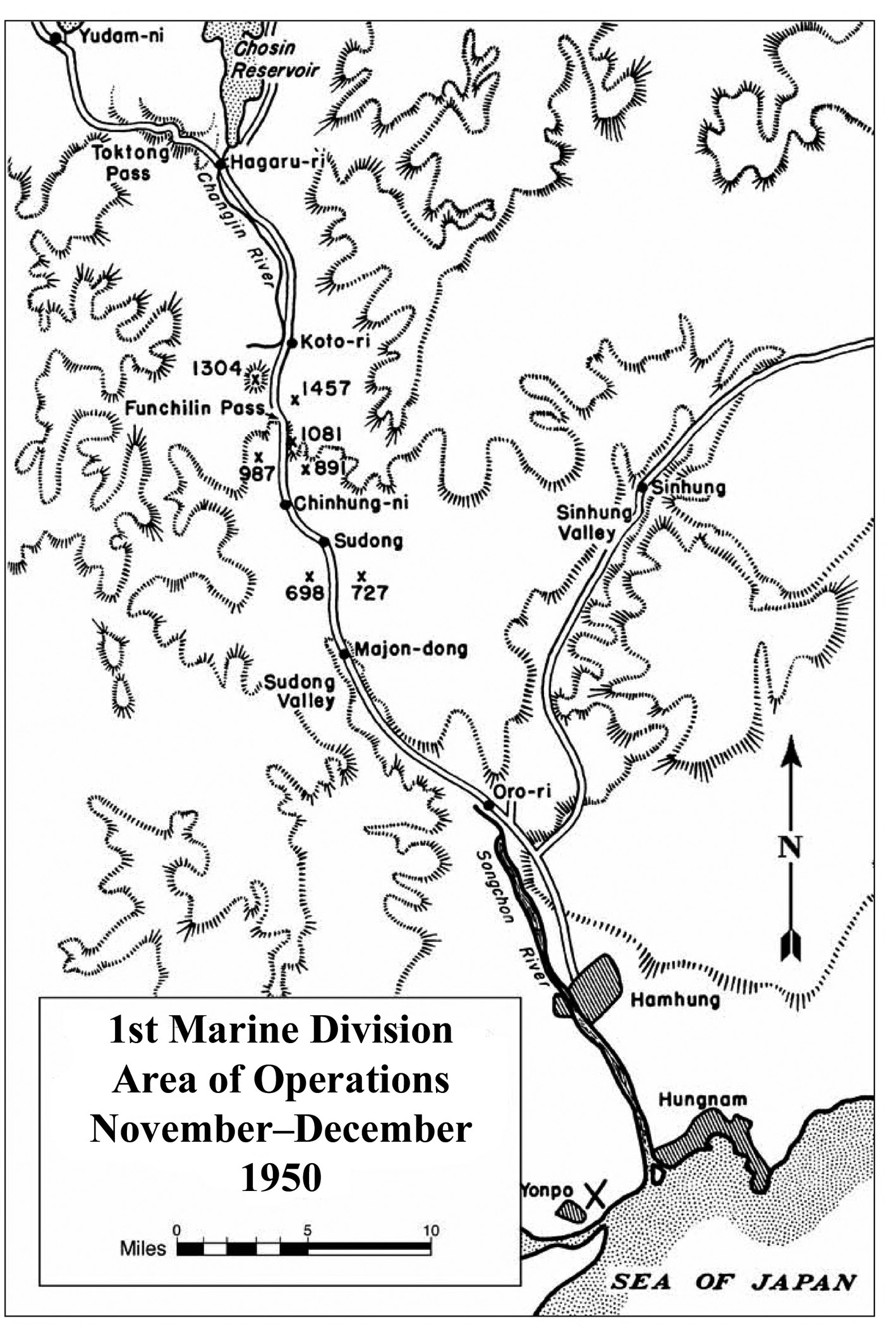

A Christmas Far from Home is less a unit-by-unit history of an extraordinary and moving episode in the Korean War, from Thanksgiving Day to Christmas in 1950, than a narrative of two fantasies. General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander in the Far East, gambled that he could end the war by Christmas and send the bulk of his armies home. In too public a fashion he promised as much. His troops in the frozen, windswept north of Korea, in the worst winter of their lives, believed despite all the evidence to the contrary that Home for Christmasor at least their being shipped out of danger and voyaging homewas somehow possible. After all, MacArthur, his medal-embellished career long celebrated by the press, was the senior fighting general in the Army.

A more realistic wish was that of an embattled Marine in that frigid, barren waste who, when asked by LIFE combat photographer David Douglas Duncan, If I were God, and could give you anything you wanted [for Christmas], what would you ask for?

Gimme tomorrow, he said.

Those two words may be the most memorable in what has been erroneously described as the forgotten war. They will reappear when they actually happened.

Over half a century later, David Halberstam wrote in 2004, the war still remained largely outside American political and cultural consciousness. The Forgotten War was the apt title of one of the best books on it. Korea was a war that seems orphaned by history. While working on his own compelling book about the war that year, he added, I chanced into the Key West, Florida library; on its shelves were some eighty-eight books on Vietnam and only four on Korea, which more or less sums up its fate in American memory.

Perhaps the library shelves lacked Korean War books because they were out being read. Rather than forgotten, the war has evoked shelves of notable histories and personal accounts, some of the latter by survivors still able to recall their roles, however small. Even this writer produced a war memoir, in distant 1964, when the events were still so sharply remembered that, respecting the privacy of the living, he disguised the identities of some who served with him. As the years pass, the memories of participants, in interviews and memoirs, become less acute, or are recalled with different passions, or are imaginatively recorded by yet another writer. Even quoting someone who was there often bumps up against another recollection that differs from an earlier account. Such anomalies are nothing new in historical narrative. There are many conflicting, dubious and fantastic accounts, despite the authority long given to Homer, of the Trojan wars.

Repelling naked aggression in the claimed national interest was the ostensible reason for Americans in Korea being seven or eight thousand miles from home. The proverbial line had to be drawn in the sand. Yet most soldiers in a combat zone, whatever the time and place, are not focused upon the complexities of geopolitics, patriot zeal, promotion in rank, medals and ribbons, nor even ultimate peace and demobilization. In the hierarchy of GI war aims, precedence always went to staying alive.

Priorities beyond tomorrow began with loyalty to your unit and to the guys at your side. Everything else, beyond enduring the war, was almost irrelevant. Finishing a war was why you fought it, and that meant, at the end or earlier, going home. No one swathed in winter gear and under relentless fire in Korea seemed interested in slogans. Remember... anything as a goad to action was meaningless. Rallying round the flag was absurdly antique. Anti-... whatever, including despised Communism, was political talk motivating politicians who did none of the fighting and were only at hazard at the ballot box.

The term Police Action is often associated, still, with Koreaand Harry S. Truman. However, the blame for labeling innocuously what was a real and bloody war does not belong to President Truman at all. At a crowded press conference in Washington shortly after the Norths invasion of the South and the beginnings of an American response, he was asked by a newsman, Mr. President, would it be correct... to call this a police action under the United Nations?

Yes, said Truman, grateful for the euphemism. That is exactly what it amounts to. We are not at war. Of course we were. Although associated since with Harry Truman, the unfortunate tag had come by way of ultraconservative California senator William Knowland, a Republican, who on the Senate floor had described the response to North Korean aggression a police action against a violator of the law of nations and the charter of the United Nations. A reporter had picked the phrase up, and it made the newspapers. But what was not an official war declared by Congress under the Constitution was nevertheless a real war. It was General MacArthur who coined the only slogan, however since tinged with irony, worth rememberingHome for Christmas.

Stanley Weintraub

Beech Hill, Newark, Delaware

A Turkey for

Thanksgiving

Turkey: a theatrical production that has failed

O rganized resistance, General MacArthur predicted confidently, not for the first time, will be terminated by Thanksgiving.... They are thoroughly whipped. The winter will destroy those we dont. The they were the North Koreansand the generals boast was to President Truman, with whom he was conferring on Wake Island on Sunday, October 15, 1950. It goes against my grain to destroy them, MacArthur deplored in mock sorrow, but they are obstinate. The Oriental values face over life.