Contents

About the Book

An inspiring account of how a family survives when everyday life is blown apart without warning.

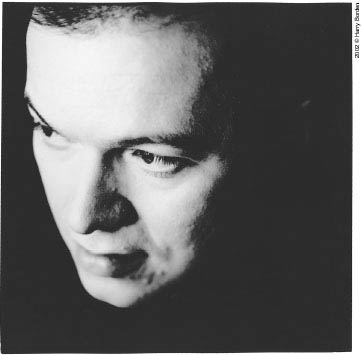

When musician Edwyn Collins, at the age of 45, suffers two devastating brain haemorrhages his doctors tell his partner Grace that if he survives, there will be little left of him. When he regains consciousness he can barely move or talk. He has aphasia an inability to use or understand language leaving him unable to communicate with his anxious family.

Yet Grace and their son Will refuse to give up hope that the Edwyn they know is coming back. Through gruelling therapy Edwyn fights to reinhabit his body and relearn almost everything he knew.

To John Kennedy Put it in the book!

PROLOGUE AUGUST 2005

O N OUR USUAL drive from Northwick Park Hospital to Harrow town centre for supper, Edwyn stuns me by bursting into song.

Im searching for the truth

Im searching for the truth

Some sweet day well get there in the end

Some sweet day well get there in the end.

A song which has sprung from nowhere, he sings it over and over as I transfer him to his wheelchair and push him to our regular haunt. Our choices are limited by the chair, and the unlovely pedestrianised shopping centre location, but Nandos has tasty free-range chicken and good access. Edwyn is in full celebratory voice all the way there, and all the way back. After six indescribably weird months, hes due to leave hospital for good in two days, so I christen it his demob song. Back on the ward, he sings it to Mark, his last remaining room-mate. Soon the two of them are belting it out together.

Mark was here before Edwyn and will be there when weve gone. He remembers our first meeting. Edwyn was stuck on a phrase at that time (something that has been a feature of his speech and language affliction), but I cant remember what it was. Mark does: The possibilities are endless. The possibilities are endless

I AM COMPOSED of my thoughts. Imagine it. Suddenly there are no more thoughts. Your brain doesnt work properly. The damage is such that you barely know who you are, the nature of your existence. The loss of your intellect, your wit, doesnt begin to describe it.

The way it was for Edwyn, for Edwyn and me, was deeper and stranger. Before we could even think about his cleverness, his fabulous sarcasm, his highly developed sense of the absurd (where they had gone? Were they coming back?), we had to wrestle with questions of simple identity.

Its impossible to imagine what it felt like to be inside Edwyns brain as he struggled to return to awareness, to self-knowledge. He describes it thus: I was peaceful and tranquil at first. No thoughts at all. Edwyn Collins, thats me, I knew that. But everything else, its gone.

Brain damage was an especial dread. For two years I would not even utter the words. I used any euphemism I could think of to avoid describing what had happened to Edwyn in these unthinkable terms. Edwyn was much more courageous. His honesty had not deserted him, nor his bluntness. He confronted his new self unflinchingly. Brain damage, I think. Im a moron.

EARLY DAYS

EDWYN COLLINS IS Scottish and so am I, but we are also Londoners. I came to the big smoke from Scotland in 1980, escaping a Glasgow that seemed cliquish and defensive. There were a lot of west of Scotland flat-earthers around then: they thought you fell off the world at the end of the M8. When I return to Glasgow these days I can barely recognise it. There is a very different, self-confident atmosphere and I remember all the things about the city that I loved.

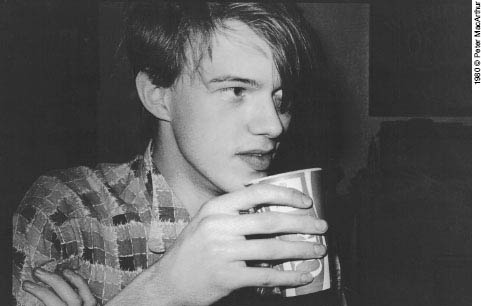

I met Edwyn for the first time in my living room in Willesden, in north-west London, on a Sunday evening in August, three months after my arrival in London. A friend from Glasgow called and asked if I could put two people up for a few days (on the floor). Edwyn was the singer in a band called Orange Juice who, together with my other guest, Alan Horne, had set up an indie label called Postcard Records of Scotland, primarily as a route to release Orange Juice records. Edwyn was tall, gangly and the most voluble of the two. Alan was a little shorter, a little rounder and had the spikier personality. They looked great, particularly Edwyn, dressed in an old-fashioned and out-of-step-with-the-times tweedy style crafted from market stalls and charity shops. Dapper and original. Neither of them drank or smoked. They had beautiful manners and a brilliant way with an anecdote. Stories and gossip, exaggerations and embellishments, a deadly eye for the absurd in every human sketch. The purpose of their mission to London was to drum up attention for the band and their fledgling label.

The sales approach for the first Orange Juice single, a song that Edwyn wrote when he was seventeen called Falling and Laughing, was to pack the boxes in the back of Alans dads Austin Maxi and travel the length and breadth of the UK, calling in at all the independent record stores they found listed in the back pages of music papers. (After one trip to London in the Maxi, the windscreen blew in just a few miles up the M1 on the way home. Rather than stop and bear the expense of getting it fixed, or maybe because they just didnt have the money, they drove all the way back to Glasgow with no windscreen. It was raining, and even hailing, at one point. For four hundred miles. Complete madness. Apparently, Edwyn was crouched on the floor in the back, sheltering from the weather, until Alan made him come up the front to suffer alongside him.)

Going for the direct, straight-to-the-counter sales approach for Falling and Laughing would result in on the spot transactions of maybe two copies, ten copies or, in one spectacular success, a hundred. I think they had pressed 1,000 and were soon sold out. Today, its a rarity of great price. Edwyn and I dont possess a single copy, like most of his records, which is common among musicians. You give them all away. Its traditional, and if you end up with none left for yourself, thats just the way it is. It doesnt matter a bit.

I N MY LIVING room on that Sunday in August, Edwyn and Alan made an arresting double act. Its very difficult to accurately describe at this distance of time the effect of their company. They were very young, very clever and very funny. They made a compelling, mesmerising impression. A journalist and DJ from Glasgow, Billy Sloan, who knew them at the time and who we are still in contact with, remembers the Postcard fraternity as being a right bunch of smartasses, very bright, but also intimidating. You took your life in your hands, somewhat, in attempting to interview them. While sarkiness was their stock in trade (Steven Daly, the erstwhile drummer and manager, reckons that they used the bulk of their energies in thinking up the next great put-down rather than concentrating on pushing the band and the label forward), they were terribly quick on the draw, deft and articulate, and could be disarmingly charming.

Next page